Collecting 'difficult memories' from the birth of two nations

- Published

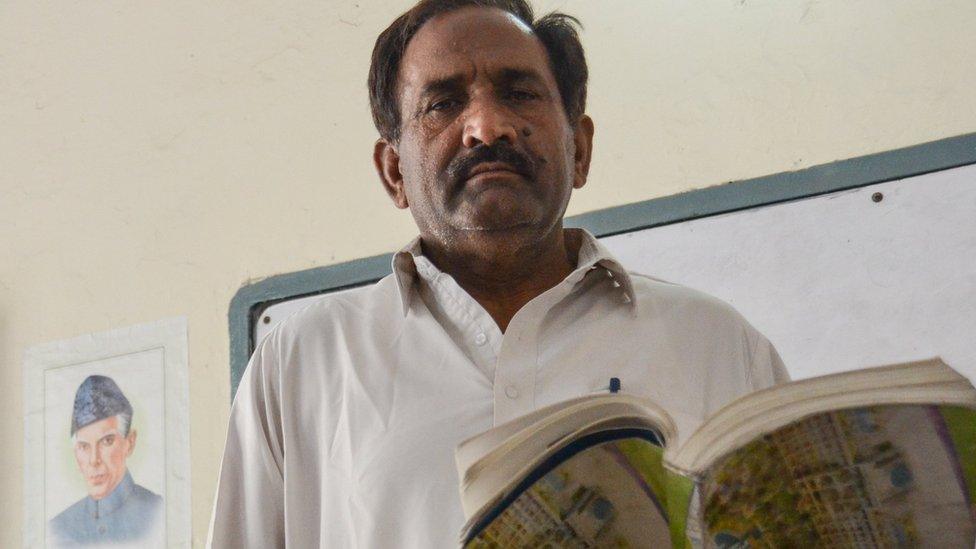

These students in Lahore are learning the officially approved version of Pakistan's history

As Pakistan and India turn 70, those who were there for the birth of the two nations are getting old. At least two civil groups are racing against time to document as much of their oral history as possible for future generations.

At a government-run school inside the historical Walled City of Lahore, a teacher lectures a class of 14-year-olds on the creation of Pakistan.

"Muslims were the rulers of this land, but they lost power to the British. They were then oppressed by both the British and the Hindus," Allah Rakha tells his class of 30 or so students.

"Hindus and Muslims are like fire and water. Their lifestyles and belief systems are totally incompatible," he says.

To illustrate his point, he comes up with an example: "Hindus rinse themselves in cow urine because they consider it sacred. For us, that is disgusting. For us, a cow is a Halal animal.

"So when the British were being driven out of India, Muslims said: 'We cannot be left at the mercy of the vile Hindu majority'. They said: 'We are two different nations and we need two separate countries'."

Allah Rakha teaches his students that Hindus and Muslims have incompatible lifestyles

Allah Rakha has been teaching this officially approved version of history for well over 30 years. He gets particularly animated when he talks about the mass violence and chaos at the time of India's Partition in 1947.

"Muslims were raped and killed by Hindus. They were driven out of their homes. Their babies were thrown in rivers of blood," he tells his captivated young audience.

A product of Pakistan's government education system, Allah Rakha firmly buys into the religiously inspired one-sided official narrative. It paints Muslims as victims and a Hindu-dominated India as their existential enemy, then and now.

Schoolchildren in Pakistan are generally discouraged, even punished, for asking questions.

And so, in all these years, it has never occurred to Allah Rakha that as a small part of the state's distorted security paradigm, he may have been doing a great disservice to young Pakistanis by sowing the seeds of religious hatred in their impressionable minds.

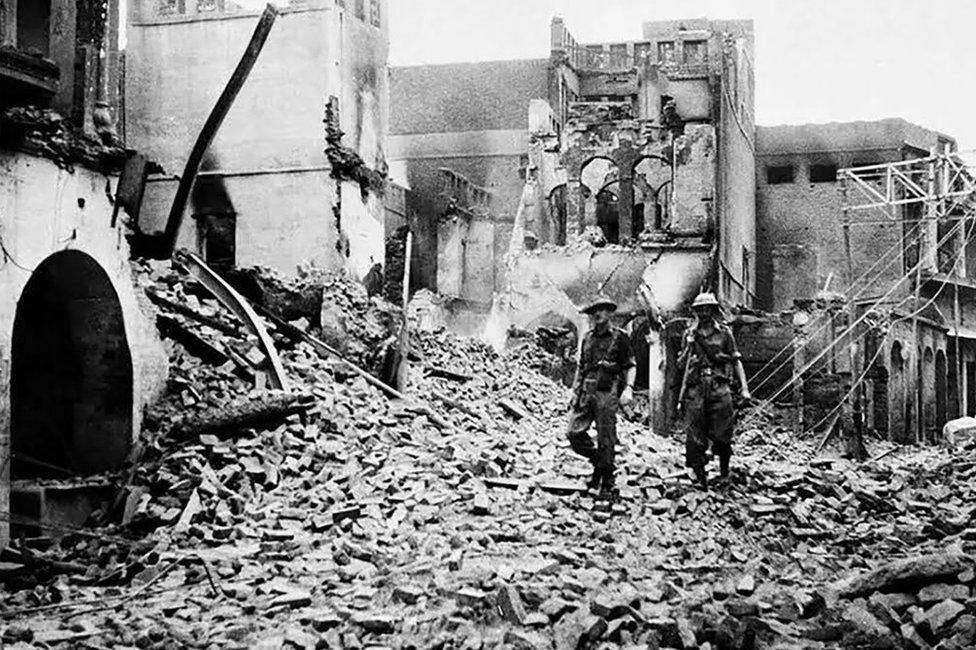

To be clear, there was plenty of religious violence in 1947. But it wasn't one-sided. Muslims were victims but they were also perpetrators of killings and lootings of Sikhs and Hindus. All three major communities were guilty of appalling atrocities.

Partition of India in August 1947

Perhaps the biggest movement of people in history, outside war and famine.

Two newly-independent states were created - India and Pakistan.

About 12 million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence.

Tens of thousands of women were abducted.

This article is part of a BBC series looking at Partition 70 years on.

Read more:

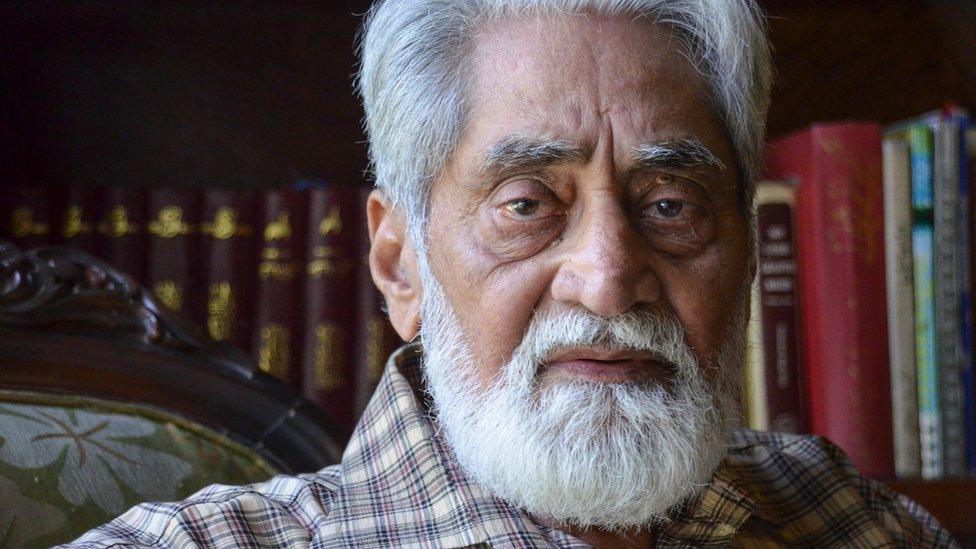

Syed Afzal Haider, a retired judge, was 16 at the time. He recalls the scene outside the Lahore Railway Station.

"Nobody was on the road except for the army and the police officers. I found members of different communities, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, stabbed, lying on the street, and the stray dogs moving among them," he said.

"That was a very pitiable situation that human corpses are being treated like this by the animals."

Partition left hundreds of thousands dead as communities turned on each other, as here in Amritsar, and millions fled as refugees

Syed Afzal Haider recalls seeing victims of all communities lying dead in the road

Mr Haider is among the first generation of Pakistani citizens with an authentic personal account of those tumultuous events. His detailed testimony is now part of a US-based oral history project called the 1947 Partition Archive., external

Starting in 2010, the digital archive project has so far collected 4,500 testimonies, making it the largest oral history project from South Asia.

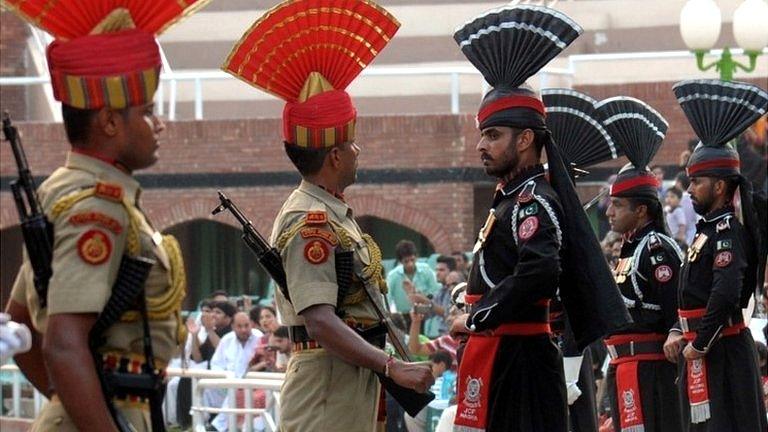

Partition was a seismic event. It affected millions of lives at the time and continues to shape the experiences of 1.6 billion people in South Asia.

"Other nations have been documenting the Holocaust, World War Two and the US bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima for decades," says Dr Guneeta Singh Bhalla, the founder of the project. "Our region woke up to it a bit late but we are getting there."

The project started by crowd sourcing witness interviews through volunteers. Dr Bhalla likes to call them "citizen historians".

"Our youngest volunteer is 13 and eldest is 87. We offer them free online training. We empower them to start by documenting testimonies of family and relatives," she told me over the phone from California.

Today, the 1947 Partition Archive has a global reach, with contributions collected from 12 countries, including US, Spain, Israel, Australia and Hong Kong.

This treasure trove of citizen's voices comes in 22 languages, though much of it is in Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi, Bangla and other regional languages of the subcontinent.

The digital project has recently partnered with Stanford University to make its audiovisual material available for online streaming.

In Pakistan, it is collaborating with Habib University, a Liberal Arts University in Karachi and Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) to host their material locally for researchers, academics and journalists. Similar collaboration is under way with universities in India.

Aaliyah Tayyebi says people can tell uplifting stories but rarely admit a role in the violence

Aaliyah Tayyebi, senior project manager of a separate oral history project at Citizen Archive of Pakistan (CAP), external, says it is "an emotional experience to listen to people dip into some of those difficult and sometimes forgotten memories".

"For many, it's simply overwhelming. Some invariably broke down," she says.

Set up in 2007 by Pakistan's Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker, Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, CAP has collected more than 2,000 testimonies of people who endured the upheaval of 1947.

"When you listen to people who experienced partition first hand, a different kind of narrative emerges," says Aaliyah Tayyebi. "It's much more personal and often vastly different from the officially-approved established narrative allowed in our history books."

But that doesn't mean it is always accurate. Researchers rarely come across those who perpetrated violence.

"When I talk to people about violence or riots, it's interesting that nobody ever talks about their involvement or their role in it," she says. "Nobody ever says, yes, I went out and I killed people or I burned down houses or I was responsible for pushing my neighbours out because of their religion."

But it's not all grim, she says. Partition certainly brought out the worst in some people. But it also brought out the best among those who had together lived in peace as neighbours.

"We do get some amazing stories of solidarity, where people stick up for their terrified neighbours and provide them shelter; where they went out of their way to welcome refugees."

It's true that in South Asia, governments have been ambivalent about coming to terms with their violent past and preserving their shared heritage.

But as she points out, it's too important a task to be left to the governments.

And that's why grassroots citizen initiatives to document history from the perspective of the people who witnessed it become all the more significant.

Shahzeb Jillani is a former BBC Pakistan correspondent

- Published27 July 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published10 March

- Published15 March 2024