Has Bangladesh's piracy amnesty been a success?

- Published

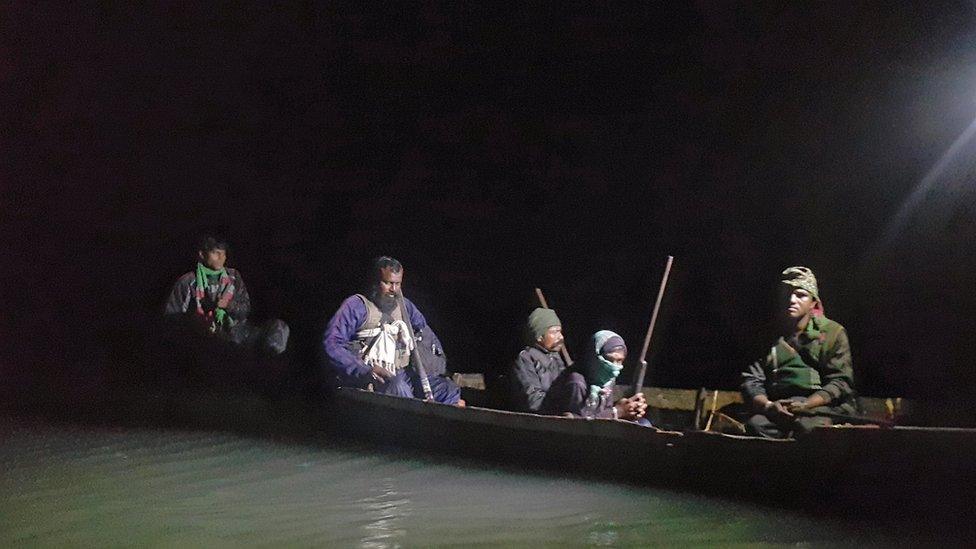

One of the pirate groups after they surrendered to the Rapid Action Battalion

Home of the Bengal tiger, the Sundarbans is the world's largest mangrove forest. It has also been a safe haven for nearly a dozen pirate gangs known for extortion and tiger poaching. Faced with deteriorating law and order and a steady decline in the number of tigers, last year the government offered an amnesty to the gangs. Has the plan worked? Masud Khan from BBC Bengali reports.

This little corner of Bagerhat town in south-western Bangladesh is no different to other sleepy towns. Set in lush green vegetation, sparsely populated, life in Bagerhat is quiet. This tranquillity is sometimes punctuated by the whining of motorcycle engines from Mostafa Sheikh's bike repair shop.

Neighbours know Mr Sheikh as a quiet little man, who keeps himself to himself. But their provincial zen may shatter should they learn that Mr Sheikh is actually the leader of the most notorious pirate gang - the infamous Master Bahini (Master Group) - which once controlled the entire southern coastline of Bangladesh.

Mr Sheikh has opted for the quiet life after surrendering to the police under a unique one-time amnesty programme offered by the government in 2016.

"My life is a bonus," he says. "One day, I was to die between the claws of a tiger, or by the fangs of a poisonous snake, or in a police shootout."

Every evening, after he shutters down his bike garage, he returns home to his wife and a daughter. "Now, I feel safe and sleep peacefully," he says.

The Master Bahini, with about 45 members, was the largest of the pirate gangs operating in the Sundarbans forest. These gangs used to extort protection money from honey collectors, crab farmers, bird catchers and illegal loggers.

They also used to launch attacks on hundreds of fishing trawlers operating in the Bay of Bengal, seizing expensive nets and other gear, and kidnapping fishermen for ransom.

'Mortal danger'

Mostafa Sheikh now runs a bike repair shop

None of the former pirates admitted to being involved in tiger poaching, but they were happy to describe how the process worked.

They said traders would obtain commissions from overseas buyers, and then contact one or more of the gangs, who either provided them with protection or who did the job themselves.

Mohammad Saiful Islam of the Forest Department said that 19 tigers were killed between 2003 and 2014, 10 of them by poachers.

There are believed to be around 180 Bengal Tigers in the Sundarbans, across both Indian and Bangladeshi territories.

So 10 tigers killed in Bangladeshi territory accounts for around 5% of the total tiger population across the vast area.

Mostafa Sheikh's gang had yearly earnings of about 60 million Bangladeshi Taka ($732,000) mainly from extortion, looting, and kidnapping; a lot of money for a Bangladeshi with no formal education.

Despite a steady inflow of cash, the pirates grew weary of running from the law.

"Life in jungle had no real value. You are always alert, always on the lookout for animals, police or rival pirate groups. All of them posed mortal dangers," says Arif Billal, a former member of the gang.

So, when Mr Sheikh decided to surrender, other members followed.

"The change of heart did not happen suddenly," says Moshin Ul Hakim, a local journalist who was involved in brokering the deal between the gangs and security forces.

He says the gangs had been under increasing pressure in recent years from a police unit known as the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), and the Coast Guard, following an anti-piracy drive by the government in 2011.

According to the RAB, more than 100 pirates had been killed in clashes with the security forces.

TV journalist Mohsin Ul Hakim (in blue shirt), speaking to some of the pirates he helped to surrender

"The prospect of an untimely death really forced the pirates to reconsider their position. So, they chose to live," says Mr Hakim.

Vacuum?

On 31 May 2016 the first group, led by Mr Sheikh, surrendered to the RAB.

The other gangs saw Mostafa and his members being returned to their families, with some cash and promises of rehabilitation, and were persuaded to follow suit. In about a year, a dozen pirate groups, consisting of around 150 members, went back to their homes.

Once the pirates surrendered, they were produced before court. Most were bailed, but those accused of major offences such as murder or rape were denied bail and detained. The BBC understands that the government is considering, as part of the promise it made to the pirates, whether to advise the attorney general to "soften up" prosecution for smaller offences. But whether this is permitted under the law is not clear.

Those who have agreed to the deal have so far received cash hand-outs from the government. With this they are setting up small businesses, such as shops, or buying auto rickshaws, to earn a living.

But it is still unclear what future the government envisages as far as the full rehabilitation is concerned. The BBC understands that the government has even consider sending some of them abroad to protect them from any possible retribution attacks.

At the moment what the government is saying is: you stop piracy now, come back to your family and friends and we'll take care of you.

A pirate gang operating at night

Mohammad Saiful Islam, the forest official from Bagerhat, says he believes the amnesty will have a "significant impact" on the tiger population.

Since the surrender, there have been no reports of poaching, he says.

But given how lucrative the trade is, there is no guarantee this will last.

Mr Islam says that the gangs have been operating under criminal "godfathers", who run an elaborate network.

This presents a major challenge for the law enforcing agencies.

"At the moment, there are no pirates in the forest. That means nobody is forcing money out of the wood collectors, crab farmers, honey collectors or kidnapping the fishing folks," says Mohsin Ul Hakim.

"[But] if you fail to take care of the godfathers who live in the background, the current vacuum will be quickly filled in by new generation of aspiring pirates.

"The money at stake is too big to ignore. And that would be a bad news for all - including the Bengal tigers."