The Rohingya crisis: Why won't Aung San Suu Kyi act?

- Published

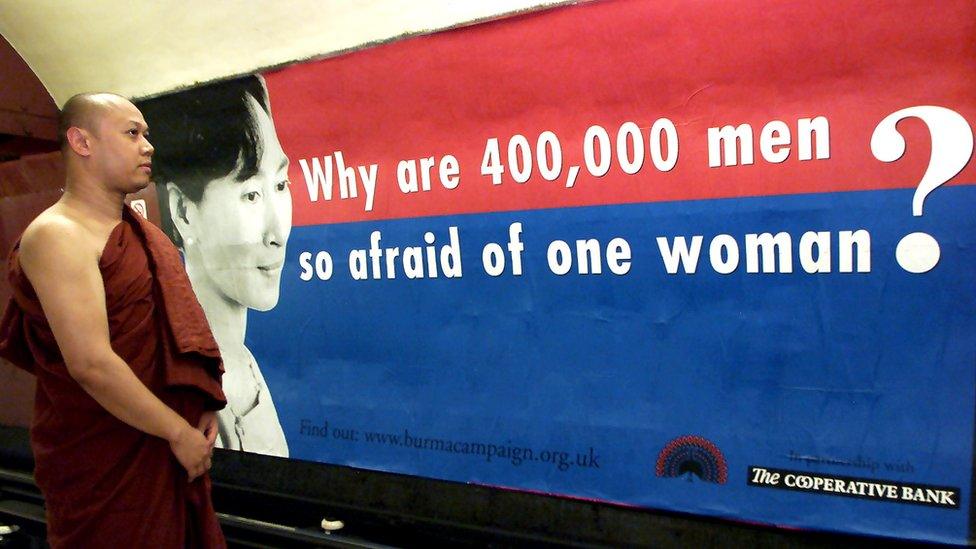

She was the perfect symbol of democracy. Highly intelligent, well-read, articulate and photogenic.

Set against this, the thuggish Burmese generals could never hope to capture the good opinion of the international media. Not that they ever cared to try.

Those of us who worked undercover in Myanmar remember a constant struggle to stay out of the way of the secret policemen and spies. We were despised by the junta and feted by the pro-democracy movement.

Defiance against tyranny

When I first encountered Aung San Suu Kyi shortly after her first release from house arrest in July 1995, she was - after Nelson Mandela - the most important global symbol of defiance against tyranny.

The world's media related how she had faced down soldiers with their rifles levelled in her direction.

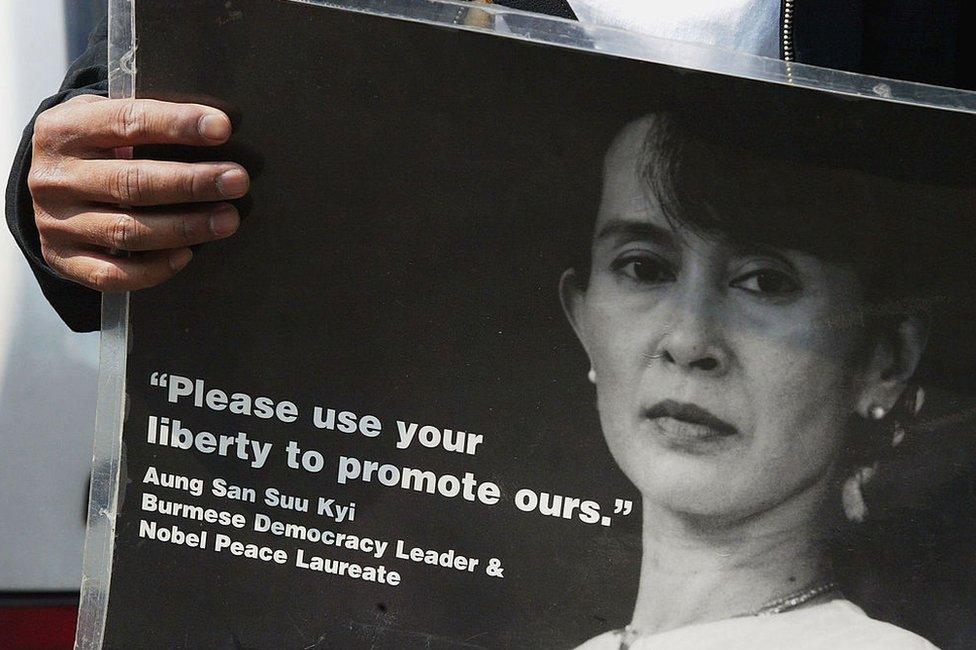

Her fight for democracy in Myanmar was backed around the world

The UN and others demanded her release from house arrest and worked hard to achieve that goal.

We listened to her address supporters at the gates of her lakeside villa about the need for tolerance and discipline.

In her interviews with me back in the 1990s, she repeatedly stressed the need for non-violence.

She was always keen to know how the African National Congress had managed the transition to majority rule in South Africa, my previous posting.

The phrase "freedom from fear" was repeated, and became the title of a bestselling book.

Aung San Suu Kyi, swarmed by supporters on her release from house arrest in 2002

It was language which Western journalists (including myself), were eager to hear. Many who found their way to Myanmar in those days were veterans of recent tragedies in Rwanda and the Balkans.

After witnessing genocide and ethnic cleansing, we were inspired by the words of the lady by the lake.

Complex ethnic rivalries

Here was a peacemaker in a world made dark by the actions of Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia, Franjo Tudjman of Croatia, and the Hutu power extremists of Rwanda.

In retrospect, we knew too little of Myanmar and its complex narratives of ethnic rivalries, deepened by poverty and manipulated over decades by military rulers. And we knew too little of Aung San Suu Kyi herself.

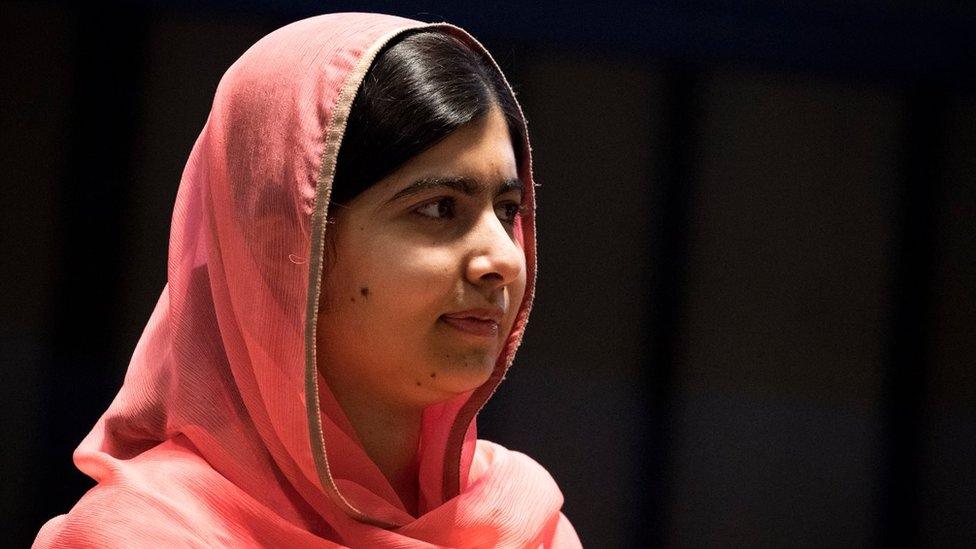

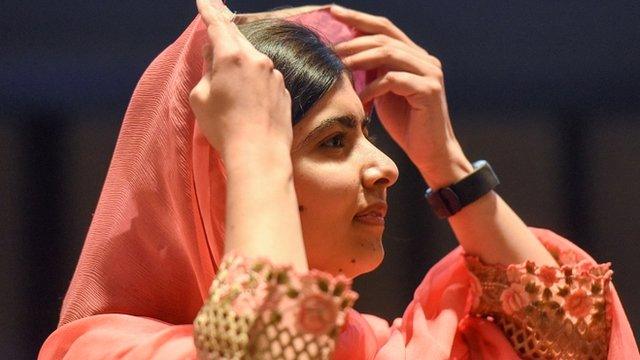

Malala has called on her fellow Nobel peace laureate to intervene

We did not calculate that the stubbornness which refused to concede to the military junta might, if she came to power, prove equally forceful when confronted with foreign criticism.

Her greatest strength in adversity could prove a defining weakness. Old friends in the international human rights movement and some previously sympathetic politicians have become strongly critical.

Anybody who has spent time in her company knows that shifting her mind when she is set on a course of action is extremely difficult.

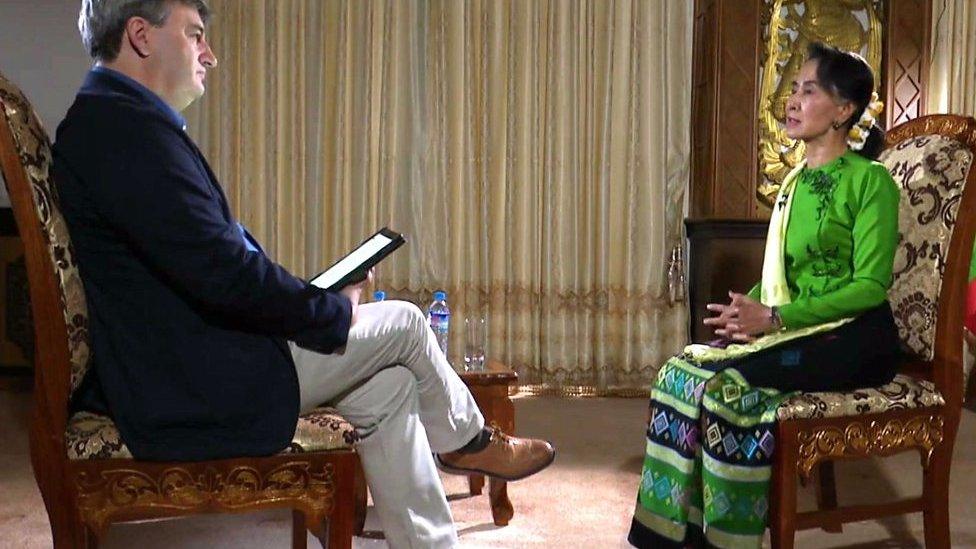

Aung San Suu Kyi talking to Fergal Keane in April 2017

Last December, when Vijay Nambiar, the UN Special Representative to Myanmar, urged Aung San Suu Kyi to visit Rakhine state, he was rebuffed.

Ethnic cleansing

As one member of her inner circle put it to me: "She will never ever be seen to do what Nambiar tells her to do."

Nor will she ever concede that the Rohingya Muslims are being subjected to ethnic cleansing, not even when tens of thousands are being burned from their homes amid widespread reports of killing and sexual violence.

This is not the first time she has faced criticism over the Rohingya.

It was the same story five years ago during a campaign that displaced more than 100,000 Rohingya.

Watch: Who are the Rohingya?

Daw Suu, as she is known, did not visit the area or speak out in defence of the persecuted minority.

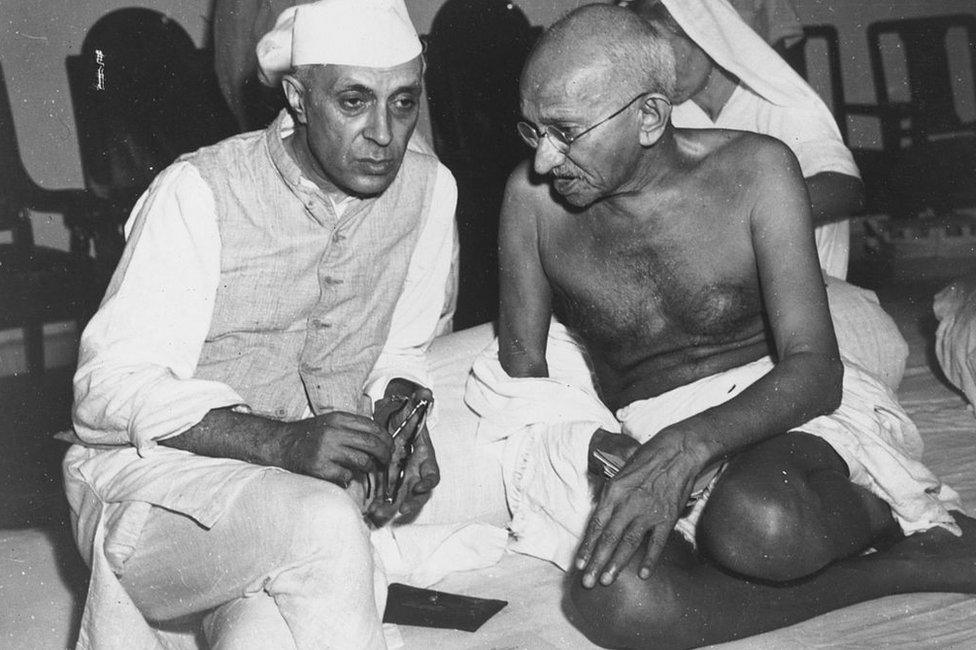

While her government has moved to tackle hate speech by Buddhist extremists, she has not made the kind of public gestures in support of Muslims made by her hero Mahatma Gandhi and his colleague Jawaharlal Nehru during the violence of India's partition.

Gandhi paid with his life and the leaders did not succeed in ending the slaughter. But both men laid down a marker about the values of the India they wished to see emerge from partition.

Jawaharlal Nehru (L) and Mahatma Gandhi publicly condemned violence against Muslims during India's partition

The memory of Nehru wading into Hindu mobs to prevent sectarian violence is one of the 20th Century's defining acts of personal courage.

Nobody expects this of Aung San Suu Kyi, but it is the absence of even rhetorical intervention that disturbs many former supporters.

The suffering of the Rohingya is a tragedy in itself. But the palls of smoke from Rakhine state is indicative of a military that feels it can carry on in the old brutal way, whatever the world says.

Tens of thousands of Rohingya have fled violence in Myanmar's Rakhine state

The action unleashed now against the Rohingya will be familiar to the residents of other ethnic areas in Myanmar such as Shan state, or in the war against the Karen.

Political cover

Aung San Suu Kyi does not control the military and they do not trust her. But her refusal to condemn well-documented military abuses provides the generals with political cover.

It goes further than silence.

Her diplomats are working with Russia and the UN to prevent criticism of the government at Security Council level, and she herself has characterised the latest violence as a problem of terrorism.

Stubbornness in the face of what she feels is unfounded criticism is part of the equation.

But there is a more troubling question: is her long-declared commitment to universal human rights partial, a concern that does not and never will embrace the beleaguered Rohingya Muslims in this Buddhist majority country?

She may yet answer that question by pressing the military to end its brutal crackdown. At this moment there is little sign of that happening.

- Published8 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published6 September 2017

- Published6 September 2017

- Published5 April 2017