North Korea: Where is the war of words with US heading?

- Published

None of the diplomatic initiatives being pursued internationally is likely to provide a magic bullet to the Korean crisis, but they may slow it down

In the wake of an escalating war of words between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, and an unprecedented night-time sortie of US B-1B bombers and F-15 fighters off the east coast of North Korea, relations between the two countries appear to be moving closer towards military conflict and hopes for a diplomatic resolution seem increasingly distant.

But are these fears exaggerated, and is the sign of resolution from the US and its regional allies in fact helping to provide clarity and reassurance at a time of maximum uncertainty?

Superficially, President Trump's UN speech signalled continuity with the policy of past presidents, making it clear that military action (albeit on a catastrophic scale sufficient to "totally destroy North Korea") would occur only if the US were "forced to defend itself or its allies".

Similarly, the dispatch of US aircraft north of the Northern Limit Line - the de facto border separating the two Korea - could be interpreted as a necessary reinforcement of deterrence intended to send an unambiguous signal to the North to avoid further provocations.

The danger of this interpretation is that it is unduly optimistic and one-sided. The history of Cold War and post-Cold War conflict on the Korean peninsula, dating from the Korean War onwards, is littered with critical misperceptions of the intentions of the competing adversaries.

By acting alone, as they did in the latest sortie, US military forces can advance the White House's strategic objectives without having to consider the South's interests

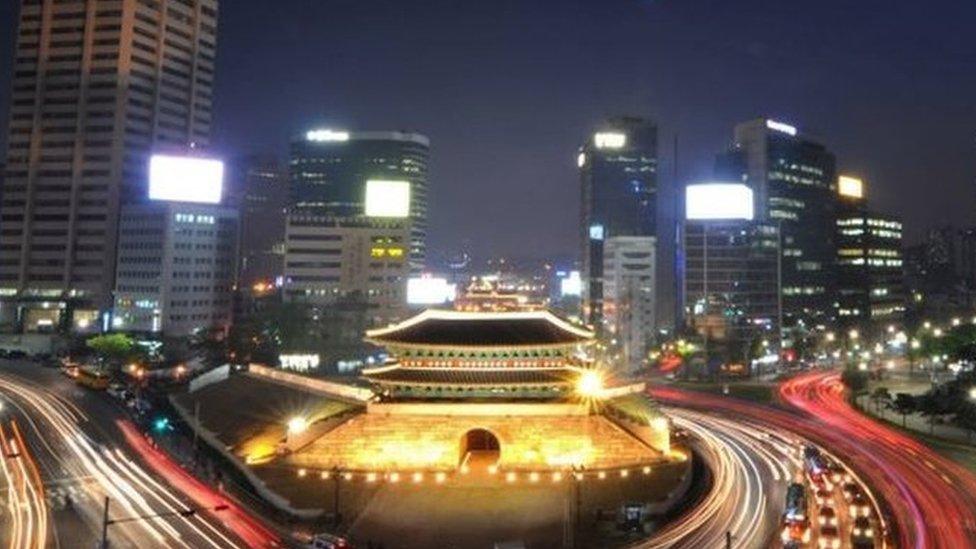

The war of words between North Korea and the US and its South Korean allies (above) is taking place during a period of maximum uncertainty

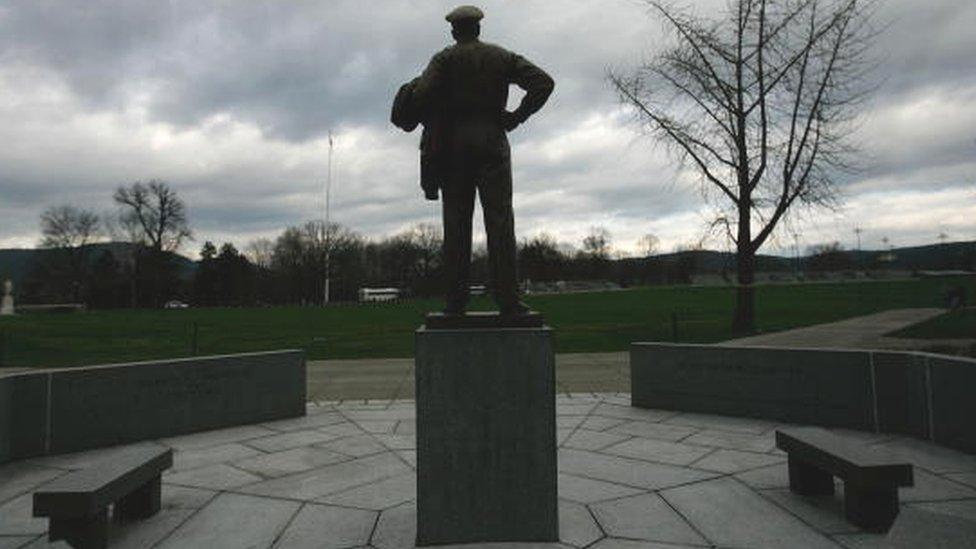

From Kim Il-sung's misplaced confidence that his attack on the South in June 1950 would not provoke a defensive response from the Truman Administration, supported by the United Nations, to Gen Douglas MacArthur's boast that he could push north beyond the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) which divides the two Koreas, reuniting the peninsula without drawing China into the war. Time and again key actors have all too often misjudged their opponents with devastating consequences.

Intelligence reports from South Korea suggest that the North has not responded to the US aerial show of force either because it failed to detect the incursion, or because its anti-aircraft facilities are too antiquated to deal with the US challenge, or potentially because the regime is trying to minimise the risk of escalation.

Yet, this cautious assessment overlooks the role of emotion in any potential escalation scenario. Mr Trump's intentionally humiliating description of Kim as "Little Rocket Man" will have been perceived in the North as deeply antagonistic to a North Korean leader for whom status and dignity are the bedrock of his legitimacy at home. Kim may therefore feel compelled to respond with further provocations, beyond the immediate, retaliatory insults that he and Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho have directed at the US president.

Military responses

One extreme option for the North would be to follow through on its threat to carry out an aerial test blast of a hydrogen bomb somewhere in the Pacific or in the waters surrounding the peninsula - an outcome that would be a major, and potentially life-threatening, escalation that could risk a military pre-emptive attack on the North by the US.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in (above) is both in style and substance pursuing an approach to the North that sets him apart from President Trump

A less obvious response, would be for the North to engage in low-level conventional provocations. These could, for example, include:

The shelling of South Korean territory (comparable to the attack on Yeonpyong island in October 2010)

The dispatch of North Korea special forces to disable the South's missile batteries or threaten government personnel below the DMZ

Cyber attacks on commercial facilities or South Korean or US military command-and-control sites in the South

There is unconfirmed speculation that prior to becoming the leader of the North, Kim Jong-un planned and co-ordinated the attack on the Cheonan, the South Korean naval vessel that sank with the loss of 46 South Korean sailors in March 2010.

That suggests that Kim's personal experience might encourage him to explore these options.

Such scenarios raise the important question of how the US would respond and with what level of co-ordination with its key South Korean ally.

President Trump's national security adviser HR McMaster has made it clear that the US has four or five different options for dealing with potential provocations, including a number of military responses.

South Korea President Moon Jae-in has apparently agreed to the recent US bomber and fighter flights, but progressive critics in the South have warned that Seoul lacks any adequate means to compel Washington to consult it before deciding on an appropriate military response.

By acting alone, as they did in the latest sortie, US military forces can advance the White House's strategic objectives without having to consider the South's interests - a situation almost certain to maximise fears of alliance de-coupling in Seoul that could damagingly destabilise US-South Korean co-operation.

President Trump's intentionally humiliating description of Kim as 'Little Rocket Man' will have been perceived in the North as deeply antagonistic

Gen Douglas MacArthur boasted that he could push north beyond the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) which divides the two Koreas, reuniting the peninsula without drawing China into the war

President Moon, both in style and substance, is pursuing an approach to the North that sets him apart from President Trump. While forcefully making the case for deterrence, he has continued to keep the door open to dialogue with the North, approving humanitarian assistance and most recently, in his speech at the UN reinforcing the case for a peaceful solution to the conflict.

On the latter point, he is joined by the Chinese and the Russians, who are increasingly anxious about the risk of escalation. Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has backed Beijing's call for a suspension deal involving a halt to joint US-South Korean military manoeuvres in return for a freeze in the North's missile and nuclear tests.

However, the suspension deal is a non-starter, given opposition in the US Congress and within the White House. There is, therefore, an urgent need to find an opportunity for renewed discussions to restart diplomacy. For now, there seems little evidence that either the US or the North Koreans are making any serious efforts to talk to one another, either via the conventional channels via the UN, or even in a low-key gathering such as the one brokered in mid-September by the Swiss government in Geneva.

In this context, the onus is on other international leaders to act. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has constructively suggested that a modified version of "Permanent Five" of France, Britain, America, Russia and China (P5) plus 2 [other countries] format used in the Iran talks might be applied to North-East Asia, presumably via a P5 plus 3 variant that might include the EU, South Korea and Japan in co-ordinated talks with North Korea.

What would a war look like?

In Moscow, the Putin administration is holding talks with Choe Son Hui, head of North Korean foreign ministry's North American division. Looking ahead to the 18 and 19 October Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, President Moon plans to send a high profile delegation for potentially constructive discussions with Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

None of these initiatives is likely to provide a magic bullet for the current crisis, but they may help to slow down the seemingly irresistible progression towards war.

Here, history may act as a useful guide. In December 1950, it was in part the intervention of British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, who announced his plans to travel to Washington to urge the Truman Administration to refrain from using nuclear weapons on the Korean peninsula, that helped alert the world to the risks of escalation and potentially devastating conflict.

Now is arguably the time for similar interventions from our national leaders, even if the prospects of success are frustratingly limited.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is Senior Lecturer in Japanese Politics and International Relations, University of Cambridge & Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia Programme, Chatham House.

- Published25 September 2017

- Published25 September 2017