Philippines unrest: Who are the Abu Sayyaf group?

- Published

Abu Sayyaf is one of several groups in the Philippines to have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State group

Abu Sayyaf is one of the smallest and most violent jihadist groups in the southern Philippines. Its name means "bearer of the sword" and it is notorious for kidnapping for ransom, and for attacks on civilians and the army.

The group is believed to have an estimated 400 members and, since 2014, several of its factions have declared their allegiance to the so-called Islamic State (IS).

In 2016, Isnilon Tontoni Hapilon, one of Abu Sayyaf's most prominent leaders, was recognised as the leader of all IS-aligned groups in the Philippines.

Filipino authorities initially characterised the pledges as opportunistic attempts to obtain funds from IS. But IS recognised some pledges and the group's official media outlets have since claimed several attacks in the southern Philippines.

Hapilon and other Abu Sayyaf militants took part in clashes against government forces in the southern Philippine city of Marawi, where militants linked to IS have fought an insurgency since May.

Over the last year and a half Abu Sayyaf has also taken several people hostage - Malaysian and Indonesian workers, Western tourists and one Filipina among them.

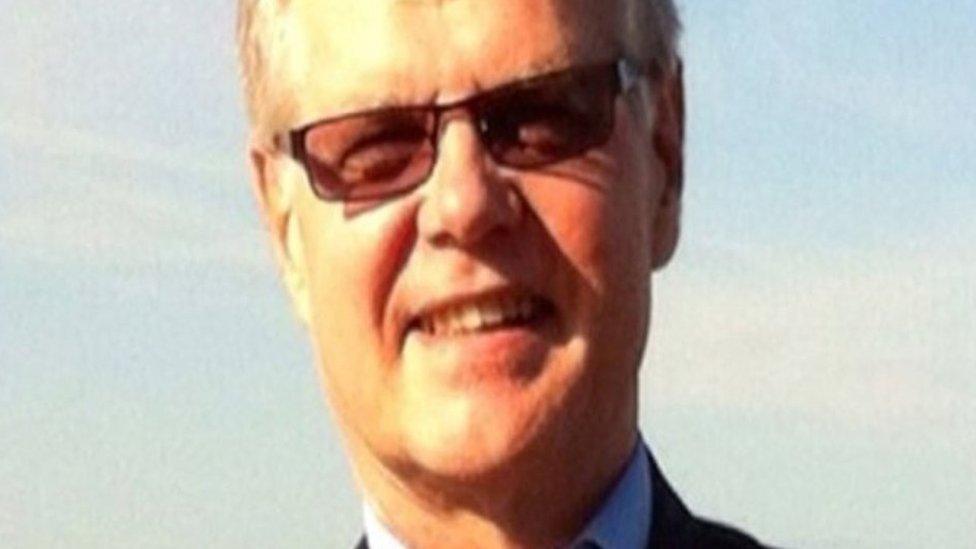

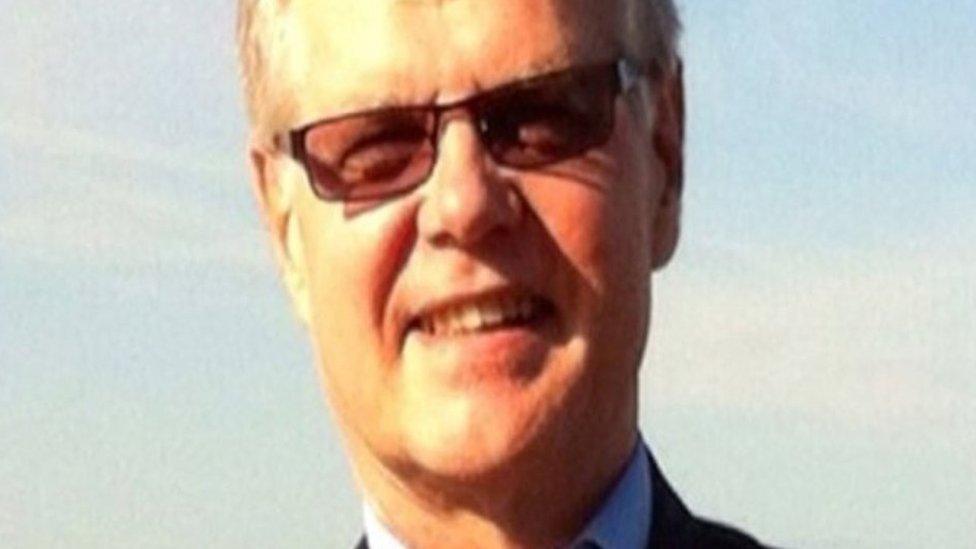

Three groups of Indonesians and Malaysians were released earlier in 2016, but two Canadians and one German were killed after their ransom deadlines passed.

Abu Sayyaf hostage John Ridsdel, 68, was killed after demands for his ransom were not met

The group has also carried out attacks outside its stronghold in the south. In 2004 it bombed a ferry in Manila Bay, killing 116 people.

What does it want?

It's not clear to what extent the entire group sympathises with IS's cause.

Abu Sayyaf has its roots in the separatist insurgency in the southern Philippines, an impoverished region where Muslims make up a majority of the population in contrast to the rest of the country, which is mainly Roman Catholic.

It broke from the broader Moro National Liberation Front in 1991 because it disagreed with the MNLF's policy of pursuing autonomy and wanted to establish an independent Islamic state.

Its founder, Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, was an Islamic preacher who fought in the Soviet-Afghan war, where he is said to have met Osama Bin Laden and been inspired by him. Al-Qaeda provided the group with funding and training when it was initially set up.

After Janjalani died, the group split into two main networks whose leaders were then killed in 2006 to 2007. Since then, Abu Sayyaf has operated as a collection of factions that work with each other through kinship or personal ties but which also occasionally compete against each other.

The beheading of a Malaysian hostage, Bernard Then, in 2015, for example, is reported to have resulted from a breakdown in negotiations as one of the two factions holding him wanted more money than was demanded, and different parties involved in the negotiations all sought a share of the ransom.

How dangerous is the group?

There has been growing evidence of ties between the Abu Sayyaf members fighting in Marawi, IS fighters in the Middle East, and jihadist sympathisers elsewhere in the region.

Authorities in Southeast Asia believe the group has co-ordinated with IS to send fighters to Malaysia to plan attacks.

In April 2016, the body of a Moroccan bomb expert, Mohammad Khattab, was discovered following a battle between the group and the Philippine army.

There are also fears that the group could be supporting terrorist activities by other IS-linked groups in the region. Investigators looking into the Jakarta attack in January said the weapons used in it had come from the southern Philippines.

While there is no evidence that Abu Sayyaf was involved in this, the group has long had ties to prominent Indonesian militant groups like Mujahidin Indonesia Timur and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI). Several JI members involved in the Bali bombings found shelter with the group after fleeing Indonesia.

Abu Sayyaf's hijacking of ships is alarming Indonesia and Malaysia, who want to work together to prevent the disruption of regional trade routes

Its kidnap of Indonesian, Malaysian and Vietnamese sailors has also prompted fears of the maritime region becoming a "new Somalia", as Indonesia's chief security minister put it, which could disrupt regional trade.

Abu Sayyaf's hostages tend to be released if the ransom demanded for them is paid. This has been the outcome for most of their hostages. The group is known to kill captives if its demands are not met.

The Kuala Lumpur-based Piracy Reporting Centre has warned ships to stay clear of small suspicious-looking vessels in the area.

What is the Philippine government doing about it?

The Philippine army has been battling militant groups in the south for years

Abu Sayyaf has withstood numerous government crackdowns over the years and has continued to mount attacks in the face of military offensives.

After taking office in June 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte threatened to "eat alive" the group's militants.

In January, he launched renewed efforts to defeat the group, with the military conducting air strikes on Abu Sayyaf sanctuaries and killing prominent militants, leading to the surrender of dozens of the group's members.

But a failed military operation to capture Isnilon Hapilon in May saw Abu Sayyaf militants re-emerge as part of the hostilities in Marawi.

Southeast Asia's governments have recently increased joint efforts to deal with the threat Abu Sayyaf poses.

The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia have launched joint air and sea patrols in the Sulu Sea, a lawless region that has long-been a hub of Islamist militancy.

The patrols may help ensnare Abu Sayyaf militants who are fleeing the Marawi battle zone.

Some observers argue that the roots of Abu Sayyaf lie in the economic and political disparities between the south and other parts of the country. "As long as Muslims continue to be oppressed, there will always be Abu Sayyaf," the vice-chairman of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, Ghazali Jaafar, has said.

BBC Monitoring reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

- Published26 April 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published10 April 2016

- Published5 July 2023