100 Women: Where do women outnumber men in science?

- Published

Is Myanmar a paragon of scientific gender equality?

Look at the following map, and it can't help but intrigue you.

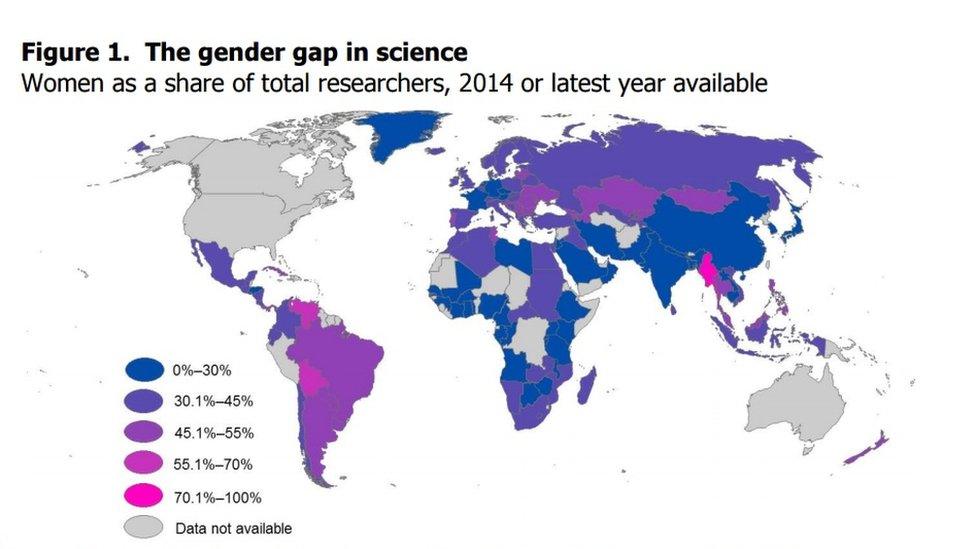

Part of a Unesco report on women in science around the world, external, countries were coloured in according to what proportion of their researchers were women - the more male-dominated the research community, the darker the shade of blue; the more women, the brighter the pink.

Sticking out from the crowd in Asia, Myanmar lit up, the pinkest of them all. According to the tables, 85.5% of researchers in Myanmar were women.

Worldwide, the figure is less than 30%.

Are 85.5% of Myanmar's researchers women?

Can the figure really be that high? Probably not - according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization itself.

Unesco told BBC News the data on which it had based its report had been gathered in 2002 by Myanmar's Ministry of Science and Technology - and some of Myanmar's universities might have included all of their teaching staff, not just those carrying out research.

Still more than half

While the figure might not be as high as 85.5%, it still appears that most researchers in Myanmar are women.

A 2013 audit of science staff at the University of Yangon found that 31 of the 45 professors and associate professors were female.

Dr Thazin Han is head of food research at the Burmese government's Department of Research and Innovation

Dr Thazin Han, head of food research at the Burmese government's Department of Research and Innovation, describes her work on using shrimp shell waste in the production of fertiliser as her "most rewarding research".

"The result is very meaningful for our farmers," she says.

Nine out of every 10 of the professors in her specialism are women, Dr Han says.

Like most Burmese scientists, she is a government employee. And that means her work isn't very lucrative.

"Due to Myanmar's economy, men need to find money for supporting their family," Dr Han says.

"My salary, at executive level, is about $300 [£230] a month."

That's not enough to support a family, she says, so men choose other professions.

Other challenges facing Myanmar's government scientists include a lack of resources, and the risk of being transferred to a university without a research department.

Dr Han herself was moved to a rural university without a research department - and was there for six years.

Last May, she was moved to a post where she could carry out research once more.

"I have a happy life again," she says.

Chemist princess

Let's look at two other countries where most researchers are women.

In Thailand, it's 53.3%, while in Tunisia, it's 53.9%.

Unesco says that both of those figures are "realistic".

Prize-winning organic chemist Prof Patchanita Thamyongkit, vice-dean of Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, was mistaken for her own secretary at a conference in 2008, external - the organiser had assumed the professor would be a man.

Prof Patchanita Thamyongkit says she's proud to call herself a feminist

She says the Thai royal family has "led the way" in encouraging the country's women to go to university.

Princess Chulabhorn studied chemistry, graduating in 1979 and going on to promote science in the country.

"In other countries, they say, 'Oh, you have the Chemist princess,'" Prof Patchanita Thamyongkit says.

An academic research job can be attractive to women for other reasons, though.

Thailand grants just three months of statutory maternity leave. And a career in academia "is not bad for being a mum".

"There's a school at the university where children can attend from Kindergarten to the 12th Grade - as soon as a faculty member gets pregnant, they can register their child," Prof Patchanita Thamyongkit says.

Obstacle course

In Tunisia, there are other challenges facing women in science.

Prof Oum Kalthoum Ben Hassine is a marine biologist who studies the biodiversity of the Mediterranean. She was born in southern Tunisia - and says conservative attitudes nearly cost her a scientific career.

"At the age of 12, my family wanted to remove me from school to get married," she says, describing her route into science as an "obstacle course".

She says she was the first girl from her city to go to high school, where a science teacher inspired her to pursue the discipline.

Historically, gender equality has been better promoted in Tunisia than most other countries in the Middle East.

Prof Ben Hassine told BBC News senior positions, such as laboratory director or professorships, were still dominated by men. In her opinion, "Tunisian academia remains strongly macho".

And certain fields are more male-dominated than others.

In Tunisia, women make up 76% of PhD graduates in life sciences but just 41% in engineering, external, according to the team led by Professor Sihem Jaziri at the EU's Shemera project.

The country also struggles with unemployment - and this isn't evenly split across the genders.

According to data from the Tunisian National Institute for Statistics, external, 19% of male graduates are unemployed - but 41% of female graduates are without a job.

According to the Shemera team in Tunisia, even those with PhDs can struggle to find work - and it's harder for women.

- Published6 November 2017

- Published5 October 2017

- Published12 May 2017