Cambodia top court dissolves main opposition CNRP party

- Published

Prime Minister Hun Sen - who has ruled for 32 years - now has no rivals

Cambodia's Supreme Court has dissolved the country's main opposition party, leaving the government with no significant competitor ahead of elections next year.

The Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) is accused of plotting to topple the government - charges it denies, and describes as politically motivated.

More than 100 party members are now banned from politics for five years.

Cambodia's Prime Minister, Hun Sen, has ruled for 32 years.

The one-time commander in Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge has long been accused of using the courts and security forces to intimidate opponents and crush dissent, but has for years allowed some measure of political opposition to his Cambodian People's Party.

The CNRP made unexpectedly strong gains in the 2013 elections, and had been set to fiercely contest next year's polls, which Hun Sen says will go ahead.

The ruling was made in response to a government complaint, and all of the CNRP's elected politicians will now lose their positions, including 55 seats in the 123-seat National Assembly.

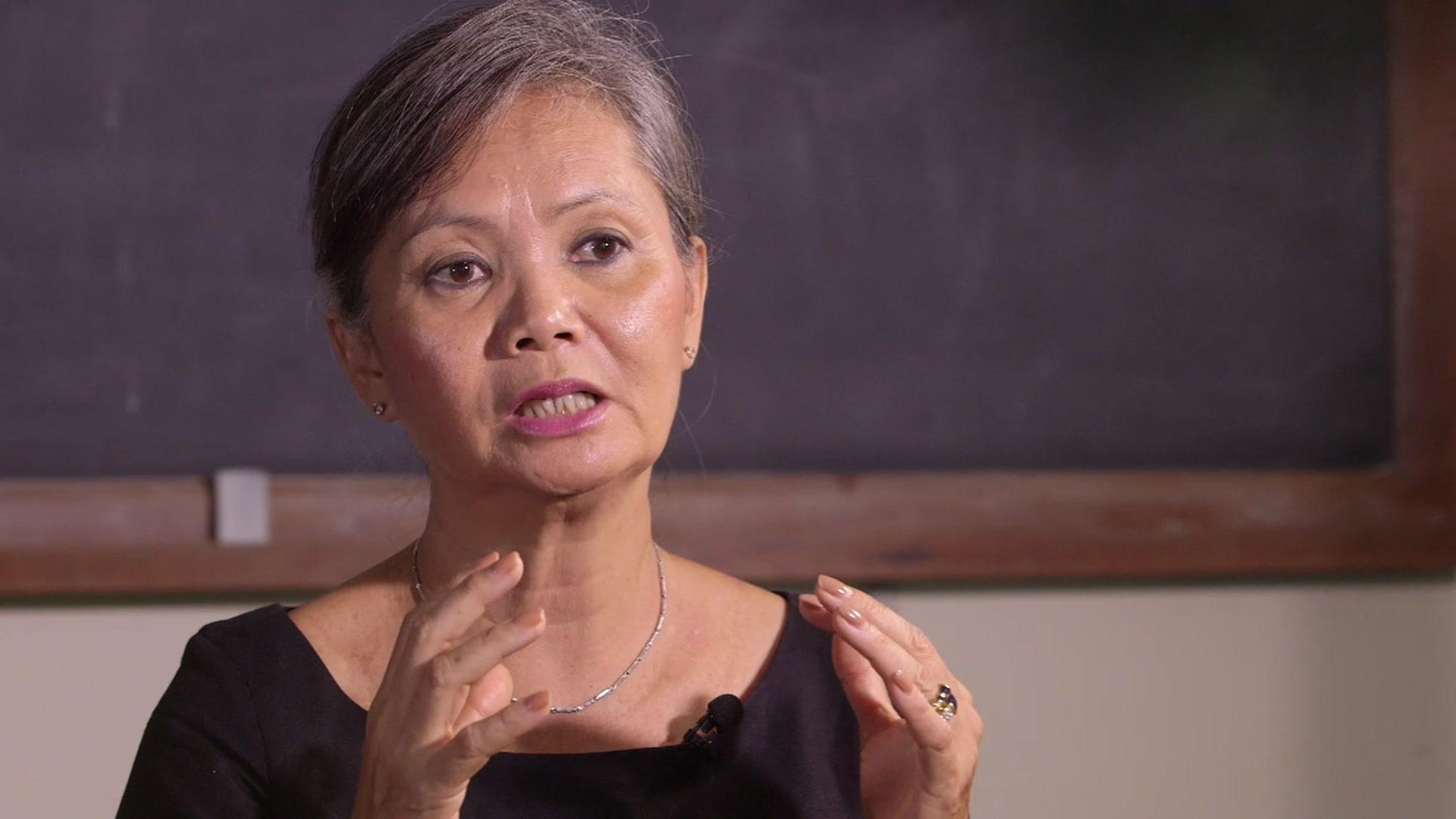

Senior CNRP politician Mu Sochua, who has fled the country along with dozens of other MPs, told the BBC that the decision marked "the end of true democracy in Cambodia".

She called for sanctions, adding: "The international community cannot let democracy die in Cambodia by refusing to see that its has been dealing with a dictator for the past three decades."

International pressure is needed, says CNRP vice-president Mu Sochua

The president of the Supreme Court - Judge Dith Munty - is a senior member of the ruling party.

In announcing his decision he said that the CNRP had effectively confessed to the charges of plotting a revolution by not sending any lawyers to the trial.

The CNRP had argued the verdict was predetermined.

A terminal blow to democracy

By Jonathan Head, BBC South East Asia correspondent

Ending the nightmare of war and revolution in Cambodia, and rebuilding civil society and a democratic political system, was one of the first great projects of the post Cold War era.

Freedom of expression and political choice were conditions built into the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement, and in the constitution two years later. The country has had regular and rowdily contested elections ever since, although through a skilful blend of populism and intimidation Hun Sen has managed to remain in power since 1985.

Now he has engineered the dissolution of the CNRP, the only real opposition party. The democracy Cambodians were promised in 1991, which has survived a rough and corrupt political culture since then, has been dealt a terminal blow.

In the past, dependence on US and European aid was a restraining influence on Hun Sen. But investment and loans from China have grown to offer an alternative source of funding for the Cambodian economy, and China does not express any concern about democracy there. This is a good time for the wily Cambodian leader to extinguish threats to his long hold on power, and get away with it.

The International Commission of Jurists said Judge Munty's role in the case "made a mockery of fair justice", while Amnesty International said the Cambodian judiciary was being used "as a political tool to silence dissent".

The Phnom Penh Post newspaper reported that a government lawyer argued in court that the opposition had tried to topple the government, external "in order to grab power, like in Yugoslavia, Serbia and Tunisia".

There was tight security around the country's top court in the capital Phnom Penh

Senior government figures have long warned of a US-backed "colour revolution" in Cambodia, alleging links between independent NGOs, US-linked media outlets and the CNRP.

The US ambassador to Cambodia has called the accusations "absurd".

The prime minister had earlier called on CNRP lawmakers to defect to his own party ahead of the ruling. He also said he was sure the party would be dissolved.

The ruling comes after a prolonged crackdown on critics and dissent. In September, CNRP leader Kem Sokha was arrested and accused of conspiring with the US to overthrow the government. He was charged with treason.

Kem Sokha (left) was charged with treason

Several US-backed media outlets and organisations have also recently been shut down or kicked out of the country.

In September, one of Cambodia's last independent newspapers, the Cambodia Daily, was forced to close after the government ordered it to pay a huge tax bill.

In 2015, then CNRP leader Sam Rainsy fled to France to escape arrest for a defamation conviction. Both him and Kem Sokha are among those banned from politics for five years.

The CNRP had presented a major threat to Hun Sen's rule

- Published15 November 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published31 October 2017

- Published3 September 2017