Pakistan protests: The political tensions behind the scenes

- Published

Protests also spread to Peshawar and other parts of the country

The situation in Islamabad had been simmering for three weeks before it erupted into violence on Saturday.

Many blame the government for allowing the protesters to grow in number and build a countrywide momentum for their movement.

When the authorities moved, they did not appear to have a good plan. The police failed to arrest leaders of the protest, and when trouble started to spill into other cities, they resorted to a controversial policy of blocking all live news channels and social media websites.

But the situation is not unprecedented in a country where the constitutionally elected civilian authority has found the rug being pulled from under its feet every two to four years.

Corruption scandals have been invariably used to topple governments through courts, and there are instances when religious hordes have stormed urban centres to undermine the legitimacy of such governments. Many suspect that these moves come with the tacit support of the military, though the military denies this.

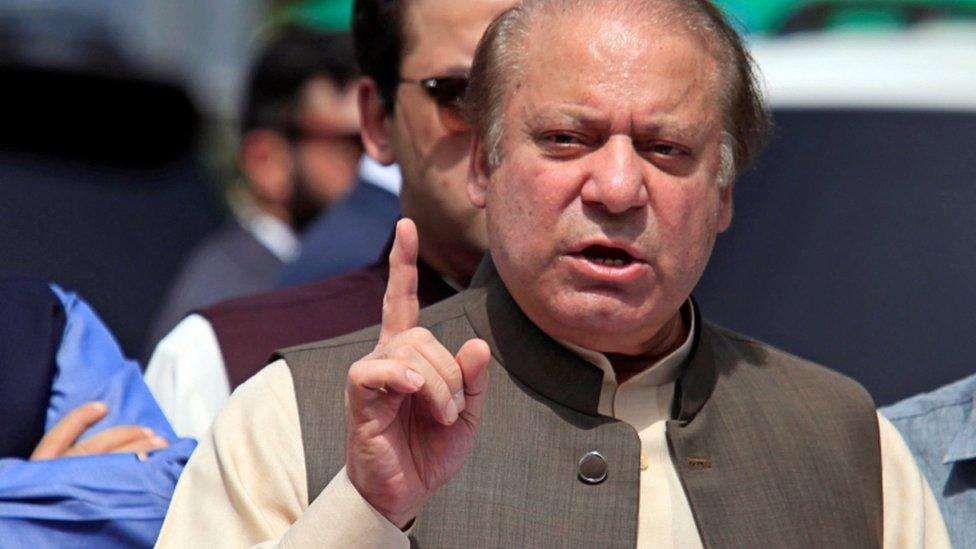

Saturday's action against the protesters came under similar circumstances. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted by the Supreme Court in a controversial corruption ruling in July. His parliamentary support was expected to diminish as a result, but that did not happen, sparking speculation that he may re-emerge as a victor in next year's elections.

Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif could make a comeback

Since Mr Sharif's party, PMLN, has considerable standing with right-wing religious voters in Punjab province, many believe the protest by the ultra-right-wing Tehrik Labbaik Ya Rasool-ul-Lah (TLYRA) is aimed at attracting some of that support towards itself.

The military stepped in on Saturday when its chief spokesman tweeted to say the army chief had told the new Prime Minister, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, that the issue of protesters should be resolved by "avoiding violence from both sides ..."

This has raised many eyebrows. Dawn newspaper in an editorial comment said it had "oddly equated the government with the protesters." Others have raised concerns over the timing of this tweet, saying it would "embolden the protesters".

Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse protesters

Hours after the tweet, the government enlisted the army's support in aid of civil administration. But security experts were of the view that the military may only secure state buildings and installations against possible attacks, and that regular army troops were unlikely to physically confront the protesters.

There has been a sense that the government was predicting such a scenario, hence its initial reluctance to move against the protesters. But its hand was forced by the top judiciary.

Islamabad High Court declared the highway sit-in illegal two weeks ago, and last week it issued contempt notices to top administration officials for failing to clear the protesters. Later the Supreme Court also initiated hearings in the case, asking the government to restore the people's right to freedom of movement in occupied areas.

Initially, the media coverage of the protest was minimal due to small numbers of the protesters and also because road blocks by obscure religious groups trying to register their presence has become a routine affair in Pakistani politics.

Six people are believed to have died in the protests and hundreds were injured, including police

But Saturday's escalating events changed this. If the sit-in continues, it will bring more pressure to bear both on the government and the military. Just how the situation pans out is hard to predict.

Aside from the blocking of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and other social media websites, television channels remain off-air and their live streaming pages have been suspended.

Meanwhile, schools have been ordered closed for two days - Monday and Tuesday - in the province of Punjab, which is home to more than 50% of the country's population. It is also the PMLN party's home base, and where the political future of Nawaz Sharif will be decided in next year's elections.

- Published17 July 2017

- Published26 November 2017