Bali volcano: How does ash affect planes?

- Published

As Bali's Mount Agung continues to spew ash, the island's only airport is closed for business. But authorities say a bigger eruption could take place, and that would affect air travel for a much wider region. So why is it so dangerous to fly into an ash cloud?

What does ash do to a plane?

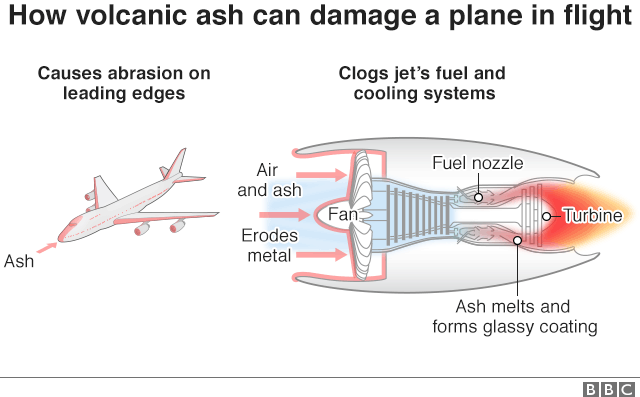

The biggest danger of flying through an ash cloud is the impact on the engines.

An erupting volcano spews ash and particles into the sky, predominantly made up of silicates.

The very high temperature inside a jet engine will melt these particles but in cooler parts of the engine, they will solidify again forming a glassy coating.

This disrupts the airflow which can lead to the engine stalling or failing completely.

Aside from shutting down the engines, ash clouds can affect many of the sensors on the plane giving, for instance, faulty speed readings.

It also affects visibility for the pilots and can affect air quality in the cabin - making oxygen masks a necessity.

The sharp particles in the ash also cause abrasions and damage to the exterior of the plane though this is not an immediate danger to the flight.

How dangerous is it?

The worst case scenario is a complete engine failure. It means a big jumbo jet may be forced to turn into a glider within minutes.

However, once an engine stops, it will cool down quickly and when restarted, there is a good chance the solidified material inside will at least partly come loose and the engine can function again.

If the engines were to fail during take-off or landing, there would not be enough time for that and a crash would be highly likely.

What can the pilots do?

Ash clouds can be hard to spot for pilots. At high altitudes, volcanic ash does not look like the dense cloud currently seen above Mount Agung.

The best visual indicator is St Elmo's fire, a glow around the plane caused by the static of the particles carried by the ash.

The first action recommended at that point is to simply turn the plane around hoping to escape the area quickly.

Bali's Mount Agung has already forced the island's airport to close

The pilot can also reduce the thrust of the engines which will lower engine temperatures making a failure less likely.

Ideally, though, pilots shouldn't even find themselves in that situation. There are nine Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres around the world each responsible for a specific region.

In the case of Bali and Indonesia, it's the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre, external that's responsible for giving advice to the international aviation industry.

Airlines can then redirect or cancel flights ahead of time.

Any lessons from the last ash cloud?

The biggest disruption to air travel in recent history was the eruption of Iceland's Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, which shut down European air space for close to two weeks.

"Yet over the past years, there's also been a few smaller airspace closures in Indonesia," Ellis Taylor of FlightGlobal told the BBC.

Ash clouds are hard to spot visually and the particles are too small to be detected by radar so in order to minimise risks, airlines have to cancel flights that might in fact be fine to fly.

As these disruptions are very costly to airlines, there is research on how planes can detect ash in flight.

"But there hasn't really been any commercialised technology coming out of that yet," Mr Taylor cautions.

Have planes ever got into serious trouble because of ash?

Yes. The most famous case is a 1982 British Airways flight en route from Kuala Lumpur to Perth, external.

The Boeing 747 with 247 passengers on board flew - without realising it - through an ash cloud over Indonesia.

The pilot first noticed St Elmo's fire on the windscreen and within minutes all four Rolls Royce engines failed.

The plane glided from 11,300m (37,000ft) to 3,650m (12,000ft) before the engines started working again and the plane was able to make a safe landing in Jakarta.

In 1982, a British Airways Boeing 747 (file pic) got into serious trouble over Indonesia

A similar scenario played out for a 1989 KLM Boeing 747 flight, one day after the eruption of Mount Redoubt in Alaska.

The jet was going from Amsterdam to Tokyo when all four engines failed. The plane dropped 4,000m before the engines could be restarted and the pilots brought it safely to Anchorage.

But "while there have been some serious incidents, there has been no aircraft accident, injury or loss of life as a result of a volcanic ash encounter," according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), external.

- Published28 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017