Why North Korea’s nuclear test is still producing aftershocks

- Published

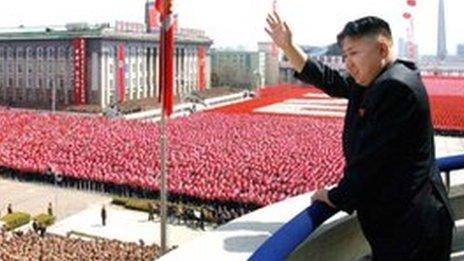

North Korea insists on its right to pursue nuclear tests

North Korea's nuclear test in September didn't just generate diplomatic shockwaves but also a 6.3 magnitude earthquake.

Aftershocks have continued ever since, and on Saturday the US Geological Survey said it had detected two more, sparking significant debate about what might be going on underground.

What happened during the nuclear test?

On 3 September, North Korea tested its most powerful nuclear bomb to date at its Punggye-ri test site in the mountains in its northwest.

Pyongyang claimed it was a hydrogen bomb, which would have made it a device many times more powerful than an atomic bomb.

Experts have expressed concerns the explosion might have been so powerful it could destabilise the surrounding mountains.

All of the tests have been conducted underground at the Punggye-ri site in the north-east

Why are aftershocks still happening?

According to the USGS, last weekend's tremors were "relaxation events". They measured a magnitude of 2.9 and 2.4.

"When you have a large nuclear test, it moves the earth's crust around the area, and it takes a while for it to fully subside. We've had a few of them since the sixth nuclear test," an official told Reuters.

The "movement of the earth's crust" is akin to the very definition of an earthquake and scientists say it is only to be expected in the weeks and months after an explosion of that magnitude.

"These aftershocks for a 6.3 magnitude nuclear test are not very surprising," Dr Jascha Polet, seismologist and professor of geophysics at California State Polytechnic University, told the BBC.

After any tremor of that size, aftershocks with declining magnitude are common, as the rock moves around and releases stress.

The area around the quake site "experiences deformation, and this creates areas of increased and decreased stress, which affects the distribution of aftershocks," Ms Polet said.

"The fact that the source of the earthquake is an explosion doesn't change how we expect the energy to redistribute," geophysicist and disaster researcher Mika McKinnon, told the BBC.

But research on explosions of a similar magnitude as the North Korea nuclear test at the Nevada Test Site in the US where over decades nuclear tests were carried out, has found that the aftershocks of these events were fewer in number and lower in magnitude.

So each location is unique.

Can tremors destroy the test site?

One of the speculations after the September test was that it would damage the tunnel system North Korea has dug into the mountains at its test site.

"The more energy you put into an area, the more unstable it's going to get," Mika McKinnon explained.

"The more tests are happening, the more energy there is, the more redistribution of stress and the more rocks will be breaking."

There have been some indications of individual tunnel collapses, she explained. "Seismic signals that look more like rock fall than anything else. That will happen more and more."

But, she adds, there is no way of really knowing whether the entire tunnel system will collapse as this is an engineering problem far more than a scientific one.

It is unclear whether this process already has rendered the current test site unusable but North Korea has hinted its next nuclear test could be above ground.

Could the tremors cause a volcanic eruption?

Near the Punggye-ri test site is the active volcano of Mount Paektu, a mountain considered holy in North Korea.

A cheerful Kim Jong-un at the top of Mount Paektu

"The seismic waves are hitting the volcano and hitting the magma beneath the volcano," Ms McKinnon explained. But she says it is "unlikely that any of this seismic energy would be sufficient to trigger an eruption".

The volcano last erupted in 1903, but the latest underground nuclear test sparked concern the tremors might trigger another eruption. This has been a point of debate, but there is little data to support this.

A study published in Nature last year predicted that the seismic waves of a hypothetical nuclear test at magnitude 7.0 would produce "stress changes", external that were not insignificant.

But, as Ms Polet points out, "little is known about what processes can and cannot trigger volcanic eruptions" and there appears to be no documented correlation between the Nevada explosions and activity in nearby volcanic areas, such as Timber Mountain and Long Valley Caldera.

There has also been no activity recorded as a result of nuclear tests conducted near the seismically active Aleutian Islands.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un still seems to trust the holy mountain.

According to Reuters, official North Korean media have reported he scaled the volcano on Saturday together with several senior officials to "emphasise his military vision".

- Published10 December 2017

- Published3 September 2017

- Published3 September 2017