Which are the countries still talking to North Korea?

- Published

North Korea is often portrayed as entirely isolated from the rest of the world, but the reality is that it has diplomatic links with almost 50 countries. Which are they, and just how close are their ties?

North Korea's pariah status appears to increase by the day.

Yet beneath its apparent isolation lies a strange anomaly, its surprisingly expansive diplomatic network.

Since North Korea's creation in 1948, it has established formal diplomatic relations with more than 160 countries and it maintains 55 embassies and consulates in 48 nations.

A smaller but still significant number of states - 25 in all - have diplomatic missions in North Korea, including the United Kingdom, Germany and Sweden, as shown in mapping of diplomatic networks by the Lowy Institute, external

China and Russia, as its then communist neighbours, were among the earliest to establish diplomatic relations after the creation of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea - as it is officially known.

The US is now pressing the rest of the world to sever its links with Pyongyang, with its representative to the UN, Nikki Haley, calling on "all nations to cut off all ties".

Among those to take action are Spain, Kuwait, Peru, Mexico, Italy and Myanmar, also known as Burma, which have all expelled ambassadors or diplomats in the past few months.

Portugal, Uganda, Singapore, UAE and the Philippines have all suspended relations or cut other ties.

But many North Korean missions around the world - and those it hosts - will remain open for business.

Some countries even appear to be stepping up ties, with Pyongyang co-operating with a number of African nations on construction projects and holding talks on energy and agriculture with others.

Diplomatic links with North Korea, however, are deeply flawed.

Only six of the 35 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) - the international organisation of the world's most developed economies - maintain a mission in Pyongyang.

The United States has never established diplomatic relations with North Korea. Neither have Japan, or South Korea.

This means the US and some of its closest Asian allies rely on other countries for the sparse information coming out of Pyongyang.

This comes from countries such as Germany, the UK and Sweden, who share a compound there and, so far, have stopped short of recalling their ambassadors, or closing North Korea's missions in their capitals.

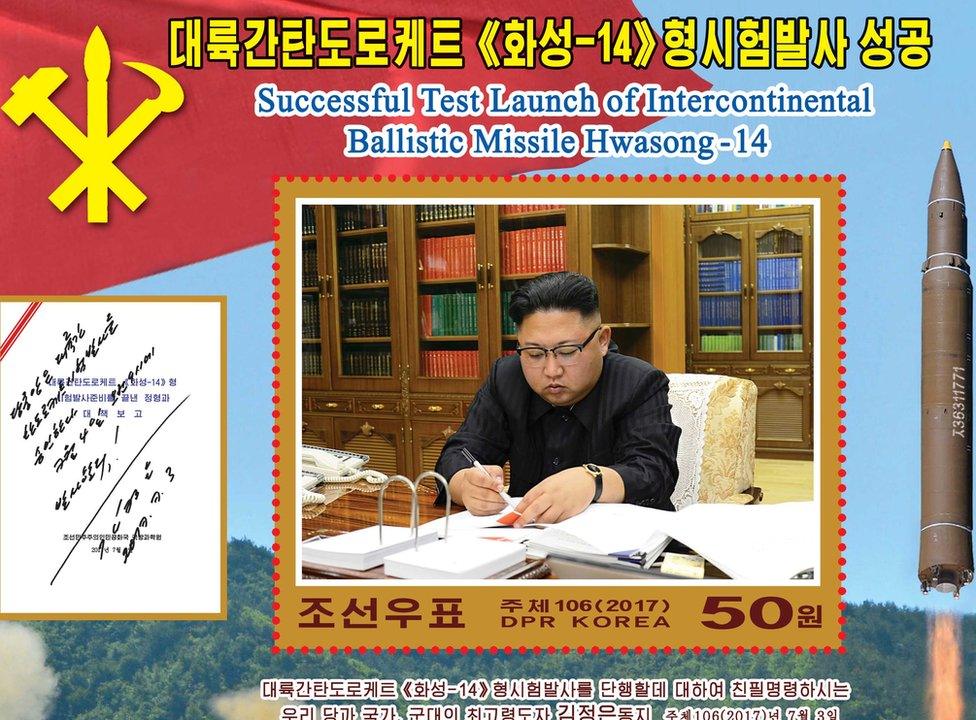

North Korea celebrated its missile tests by issuing stamps

North Korea's network of missions in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa has been crucial for generating income, both legal and illicit, and evading the ever-expanding dragnet of UN and unilateral sanctions.

The embassies are largely self-funding, and allegations that they operate as fronts for illicit activities are rife.

European hosts of North Korean missions have complained of embassy buildings being illegally sublet to local businesses.

In Pakistan, a country historically sympathetic to Pyongyang, a burglary at the residence of a North Korean diplomat raised suspicions that he may have been involved in large-scale booze bootlegging.

On both sides, intelligence agencies are suspicious of each other's officials.

They closely monitor diplomats and subject them to tight travel restrictions.

North Korea also places its own diplomats under intensive counter-intelligence scrutiny, fearing they could defect.

Given all of these problems, the obvious question is what can diplomacy achieve?

For some socialist or communist countries, such as Cuba, Venezuela and Laos, a relationship with North Korea brings a semblance of mutual ideological support.

But these days, such fraternal diplomatic ties are sustained more by a common strand of anti-Americanism than shared ideology - as is also the case with Syria and Iran.

Wherever they are posted, Pyongyang's diplomats are expected to foster pro-government support and rebut "hostile" sentiments.

This can sometimes be taken to unexpected lengths, for example berating bemused barbers in London for criticising Kim Jong-un's haircut.

Western countries that host missions and remain in Pyongyang, such as Germany, see value in keeping diplomatic lines of communication open, believing diplomacy is the best solution for the Korea problem.

They can also provide an invaluable service: it was Swedish diplomats, for example, who were permitted access to American student Otto Warmbier, who was arrested in Pyongyang in 2016 and died shortly after his return to the US.

A former UK ambassador to Pyongyang argued that an embassy there was worthwhile, cost little and would be "in a good position to act as the international community's eyes and ears in a potentially volatile situation".

The US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has indicated that the US may now be now willing to talk to North Korea if it "earns its way back to the table".

But whatever the Trump administration's line on the value of diplomacy - either with "the Hermit State" or the rest of the world - the fragile state of North Korea's diplomatic network is the exception in the modern era.

The Lowy Institute' mapping of diplomatic links shows that few countries' networks are shrinking, external.

Only eight of the 43 OECD and G20 countries have reduced their footprint in the past two years, despite austerity budgets since the financial crisis.

Twenty states actually expanded their diplomatic network - Hungary, Turkey and Australia among them.

The role of embassies as the shopfront of diplomacy appears to be adapting and surviving.

That is the case even for one of the world's most isolated, embattled regimes.

While there are links, however fragile, between Pyongyang and the rest of the world, diplomatic options with North Korea are not yet exhausted.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from Alex Oliver,director of the Diplomacy and Public Opinion Program, external at Australia-based international policy think tank the Lowy Institute, and Euan Graham, director of its International Security Program, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published19 December 2017

- Published19 December 2017

- Published19 December 2017