Papua New Guinea quake: An invisible disaster which could change life forever

- Published

Small nomadic communities have been thrown together in makeshift camps

Nearly two weeks after a powerful earthquake hit Papua New Guinea (PNG), officials still do not know what the situation is in the remote worst-affected areas. There are fears traditional life in this remote region could have been changed forever, writes Anna Jones.

"The landslides are massive," says Karen Allen, an aid worker with Unicef in PNG.

"There's nothing left of whole mountainsides where there used to be villages. There's been a massive outpouring of grief, shock and and fear, on top of the injuries and hunger."

Earthquakes happen a lot in the Pacific, home to the ever-active Ring of Fire, and news coverage of them tends to follow a familiar pattern.

Automated reports of tremors are quickly followed by official estimates of damage. Casualty figures emerge over the next few hours and a well-rehearsed recovery effort swings into action. Dramatic images and miracle rescues sweep the disaster zone on to global front pages, triggering a rush of donations.

What basic infrastructure there was has been badly damaged making it hard to reach remote areas

Little of this happened in PNG after the 7.5-magnitude quake on the morning of 26 February because the people worst affected are some of the most remote communities on Earth. Only a handful of images, vital if a quake is to make the headlines, emerged in the first few days.

How great is the need?

In a vast area home to nearly half a million people, it is estimated that 275,000 are in urgent need of emergency aid, and 300,000 have no shelter. By Friday more than 100 people were confirmed dead, but it is still impossible to know whether anyone in the isolated mountain areas has survived.

"Many of these homes are built on stilts on the mountainside so every single one collapsed," Ms Allen told the BBC. "Homes, gardens and pathways. Rivers have filled up, bringing a risk of flooding."

Seismologists say PNG has not had a quake like this for nearly 100 years, she says.

"There are almost no 100-year-olds in Papua New Guinea, so nobody had any memory of means of preparing for this."

Among the people arriving at the Huiya camp was a 15-year-old who had lost his entire family

These small villages, where people lived semi-nomadically and off the land, have never had road connections. But even jungle pathways were lost, leaving people to make arduous journeys carrying their children and salvaged belongings.

And ground has not stopped shaking - there have been several more major quakes since the first and more than 100 aftershocks.

"In the first few days, people were just lying on the ground scared to death, with tremors still occurring," Ms Allen told the BBC.

"People have started slowly walking away from areas that are still shaking. We are starting to see a constant traces of displaced people forming around towns and hospitals."

How are local people helping each other?

Scott Waide, deputy editor at local news organisation EMTV, spoke to the BBC after visiting an informal camp in a village called Huiya, on the border of Hela and Southern Highlands provinces.

More than 2,000 people have gathered there, setting aside generations of at times bloody clan rivalry to help each other. Among them, a 15-year-old boy whose whole family was killed. , external

"They call it a care centre - it's offering support but there's very little food and water," said Mr Waide.

"People are organising themselves because it's been difficult for the government to get in. When people get a mobile phone signal they are sending texts to the authorities saying 'we have 2,000 people here and no food or water - can you send help?'"

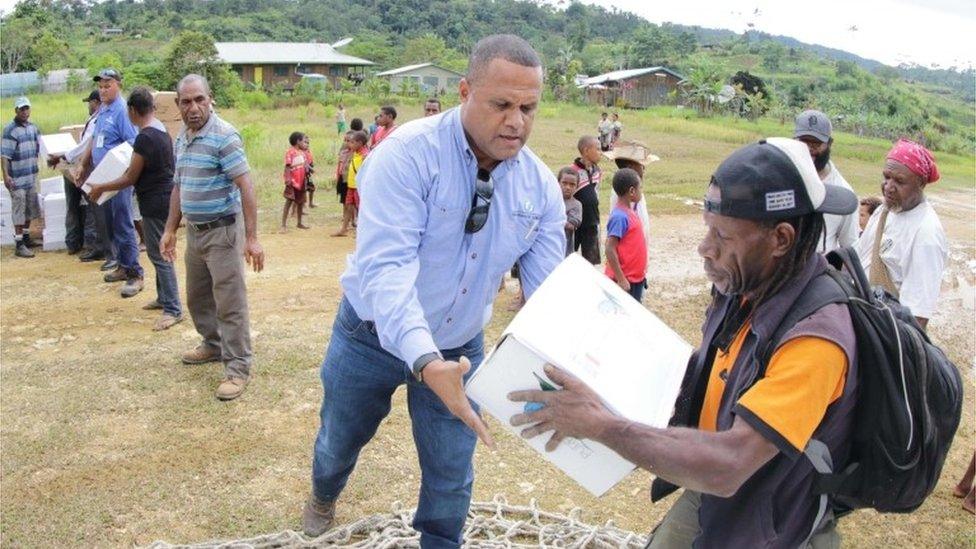

Displaced people at a camp in Huiya village

The political process of freeing up and delivering aid has been frustratingly slow, he says, while the national disaster agency has found itself unprepared to cope with a disaster people are calling unprecedented.

People who have watched as oil and gas companies rapidly built up their industrial infrastructure over recent years are asking why that same speed cannot now be applied to them.

"At the airfield when we flew in people were waiting outside the fence asking 'Why are we not seeing aircraft landing with supplies? Why are we not seeing people being evacuated to Tari?'"

But Tari and nearby Mendi are themselves small, with only basic facilities, and are badly damaged. Scores of people were killed there. Mendi's small hospital is still only partly operational. Tari's has only ever had three doctors - they have worked non-stop since the quake, says Mr Waide.

How will children be affected?

Prime Minister Peter O'Neill has warned there will be "no quick fix" and the damage will take "months and years to be repaired".

"The social damage to our communities is large, and this earthquake will be the source of sadness and sorrow for generations to come," he said on Thursday while visiting the quake zone.

Troops and medics are being deployed across the region, working alongside charities and churches to get people back on their feet.

Soldiers and military medics are being sent out to aid the rescue and recovery operation

But aid workers say it is clear that PNG's development has been firmly set back.

About 16% of PNG children were already acutely malnourished, says Ms Allen, while only a fifth had access to a toilet. There are real concerns now about diseases breaking out as unvaccinated children are brought together in poorly maintained camps.

Teachers have also been mobilised to help with rescue efforts - some of them are being dropped by helicopter in the middle of the jungle to find survivors - so those schools that stayed standing remain closed.

"Two of the provinces have said they may not open their schools for the rest of the year," said Ms Allen.

Additionally, ExxonMobil Corp said it would not be able to operate its $19bn (£13.7bn) liquid natural gas plant for at least eight weeks, a major economic loss for the region.

Employees of oil companies in the region have been taking part in relief operations

"This is a country of extremes," says Mr Waide. "You have people who can access the internet but still choose to live their traditional nomadic lifestyles."

Could such widespread devastation change a way of life forever?

"I was with the finance minister, a local politician, as he was talking to people in Huiya," says Mr Waide.

"He suggested that Hela is a really difficult province to manage and it would be good if we started thinking about moving you from your lands to a central location," he says.

"They may have to do that over the next five years because it's just too dangerous. Somebody told me, 'This is where my mother bore me and my ancestors lived. How can I leave and where would I go?'"

"But they already see that they will have to move and there is a sense of sadness right now."