Spring in Tashkent: Is Uzbekistan really opening up?

- Published

There's optimism over reforms in Uzbekistan but no way of knowing how far they'll go

Uzbekistan is a country that has long been in the shadows, but this week the once repressive and secretive Central Asian state invited the media in for an international summit on the peace process in Afghanistan. It was a chance for BBC Uzbek's Ibrat Safo to return home for the first time in more than 10 years.

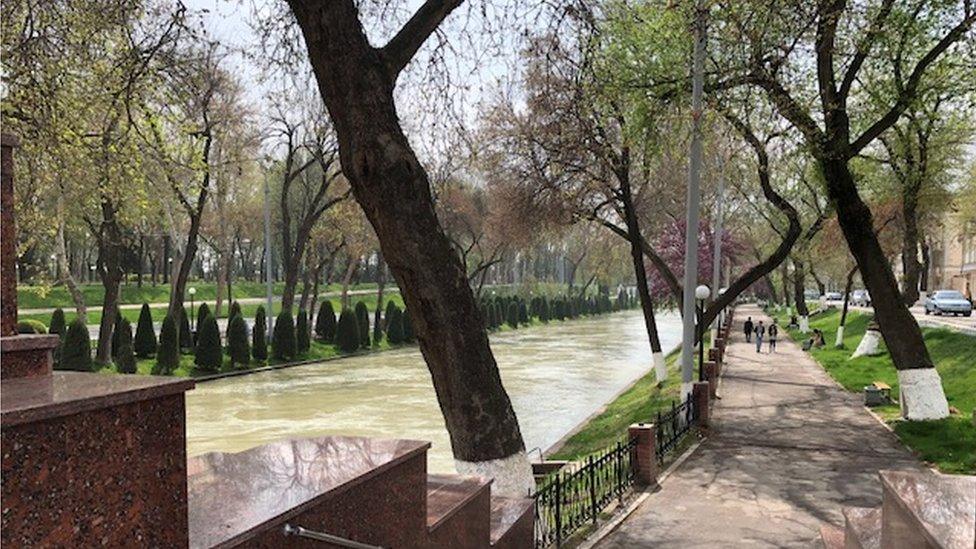

Spring always comes suddenly in Tashkent.

One day it's cold and grey; the next, the city's almond and apricot trees burst into blossom.

This year the streets are also festooned with fairy lights to celebrate Navruz, the tradition spring festival.

Even in the pouring rain there's a new sense of hope and anticipation in the air.

After the death President Islam Karimov in 2016, Uzbekistan has started to open up.

And this week's Afghan peace conference, with delegates and journalists flying in from all over the world, was the highest-profile indication yet of a new willingness to re-engage with the world.

Returning home

For me it was a chance to return home to work for the first time since the BBC had to leave Uzbekistan in the aftermath of the unrest and violence in the town of Andijan in 2005.

And I wasn't the only one. As I walked into the grand white marble conference media centre I met many familiar faces from the old Tashkent press corps, also returning for the first time in many years.

The peace conference was headline news on all the local TV news programmes and everyone seemed to know about it.

"You here for the Afghan summit?" a taxi driver surprised me by asking on the first day.

Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power in 2016

Like many people here, he saw the conference as yet another sign that the new President Shavkat Mirziyoyev is trying do things differently.

A peace summit makes sense for people here because neighbouring Afghanistan is not just a security nightmare right on their doorstep, it's also a potentially huge market for Uzbek goods and services.

People in Tashkent think things really are beginning to change

In this country of 31 million people where the economy has been stagnating for decades, everyone is hoping for some better news.

"I work in a factory assembling washing machines," my taxi driver told me. "Our products are more expensive now because Mirziyoyev slapped tariffs on Chinese spare parts."

"So that's bad for you, then? I asked.

"Oh no," he replied. "We need to start making our own spare parts. I think the president is totally doing the right thing."

It was first of many similar conversations, in the brief few days I was reporting in Tashkent, which gave me a sense that things really are beginning to change.

A more open media

BBC Uzbek’s Ibrat Safo returned to his home country for the first time in more than 10 years

Chatting to local reporters as we waited for the latest news from the conference floor, I heard many stories about the way the media is opening up.

State television news, once famous for ignoring 9/11 and headlining bulletins with stories about cement factories, has suddenly become lively and interesting.

Journalists are competitive, covering real stories that matter to ordinary people - life in a village with no electricity, a teacher killed sweeping the roads for the local council.

Of course there are still limits to this new freedom. One reporter told me she was made to take down an online article after she criticised a monopoly business owned by a local official.

Former President Islam Karimov died in 2016 but still casts a long shadow over Uzbek society

And while people are keen to praise the new president, there's still a reluctance to say anything too critical about his predecessor, whose rule over more than two decades was marred by allegations of corruption and human rights abuses.

In a brief break between sessions, I went to visit a relative in hospital.

On the wall there were framed portraits of both the old and new presidents. "They're still not ready to put that one in the bin," one patient muttered darkly, gesturing at Mr Karimov.

At the peace conference, the new and more open Uzbekistan was very much in evidence.

The presidents of both Uzbekistan and Afghanistan attended the session, as did the EU's foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini, and senior officials from the United Nations and the 23 countries taking part, including the US and the UK.

Deputy head of the Senate Sodyk Safoyev spoke of a new political atmosphere

Sodyk Safoyev, a former foreign minister and now deputy head of the Uzbek Senate, told the BBC the conference was happening because of what he called Uzbekistan's "renewed foreign policy" over the past year and a half.

"A completely new political atmosphere has been created in Central Asia," he said. "There's mutual trust, and mutual readiness to resolve the most sensitive issues in the region."

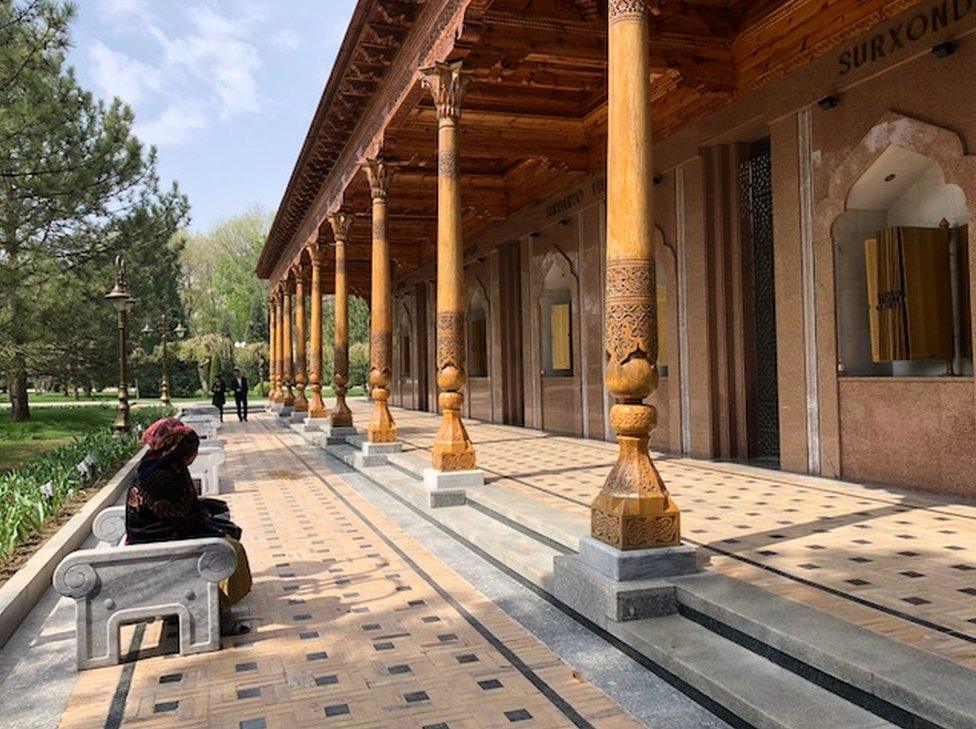

Tashkent's Academy of Art is currently running an exhibition about... Caravaggio

No-one was expecting the peace conference to deliver any breakthroughs. But that was never the point. This was a chance for Uzbekistan to reclaim its place on the international stage and to show solidarity for a peace process that matters not just for Afghanistan, but for all of Central Asia.

It ended with a declaration supporting efforts to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table, and underlining that Afghans must lead the peace process themselves.

As the Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's convoy swept through the streets on his way back to the airport, like me he will have seen the wide avenues, shiny shopping centres and grand apartment buildings of a new and very different Tashkent.

Spring has come to Uzbekistan, and I left hoping the new beginnings in my country might one day be echoed in a new day for peace in Afghanistan.

- Published26 November 2017

- Published30 October 2024

- Published30 October 2024