Bhutan's 'Shangri-La' caught between two rival superpowers

- Published

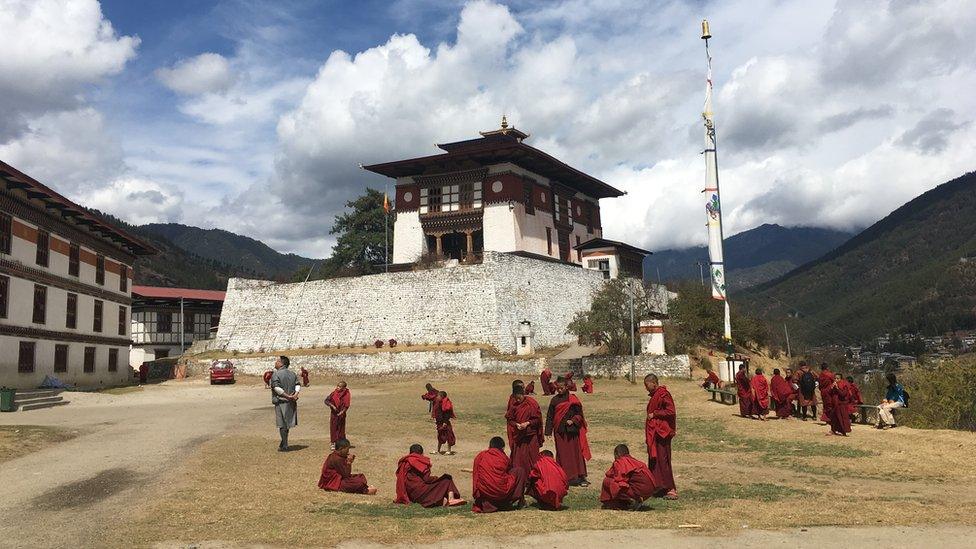

Bhutan has beautiful hilltops and monasteries

With its scenic mountains and stunning Buddhist monasteries on hilltops, Bhutan is a traveller's dream and described by some as the last Shangri-La - a mystical beautiful place where everything is perfection.

The country's capital, Thimphu, is a refreshing delight to those who are tired of traffic and pollution in mega cities. The fresh air and the lush green mountains and snow peaks in the distance offer a visual treat.

Men, women and children calmly walk around in the country's traditional attire. It is probably the only country in the world where there are no traffic signals - just traffic police officers giving hand signals.

But beneath the surface, this picture-postcard country has been experiencing an undercurrent of tension and nervousness since last year.

Sandwiched between two Asian giants - China in the north and India in the south - the Himalayan nation, with a population of about 800,000, was anxious when troops from the two military powers squared up to each other over their border dispute.

The flare-up was in a strategic plateau called Doklam - situated in the tri-junction between India, Bhutan and China.

The remote mountainous region of Doklam is disputed. Bhutan and China both claim the area. India supports Bhutan's claim over it.

When China started to expand an unpaved road in June 2017, Indian troops went across and stopped the work, triggering a face-off between the two sides.

Delhi argued that the road had security implications. The fear is that in any future conflict, Chinese troops can use it to seize India's strategically important Siliguri Corridor, known as the Chicken's Neck, which connects the Indian mainland with its north-eastern states.

Some experts said the fears were far-fetched.

Namgay Zam: "Most people don't even know where Doklam is"

But many Bhutanese were unaware of the strategic importance of Doklam.

"Doklam was insignificant until it became a controversial issue a few months ago. Most Bhutanese don't even know where Doklam is," says Namgay Zam, a multimedia journalist in Thimphu.

She adds: "It became a matter of contention and discussion only after it blew up as a controversial issue between China and India".

The tense stand-off between Chinese and Indian troops in Doklam raised concerns among many Bhutanese that it could trigger a war between the two Asian giants. Beijing angrily denounced what it described as a "trespass of Indian troops", external.

After weeks of hectic diplomacy by the Indian and Chinese leadership, the 73-day face-off was brought to an end. Indian troops finally withdrew.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The Bhutanese government refuses to publicly discuss the Doklam stand-off, but it issued a cautious statement, external last August welcoming what it described as "the disengagement by the two sides".

Many in Bhutan say the flare up was a wakeup call.

There was a passionate discussion on social media over whether it was time for Bhutan to settle its border dispute with China and follow an independent foreign policy. Some even argued that Bhutan should come out of India's influence.

Disputes along the long border between China and India remain unresolved in several areas

After Tibet was invaded and annexed by China in the 1950s, Bhutan immediately turned south - towards India - for friendship and security. Since then it has been under India's sphere of influence.

India provides economic, military and technical help to Bhutan. The Himalayan nation is the largest recipient of India's foreign aid. India gave nearly $800 million to Bhutan's, external last five-year economic plan.

Hundreds of Indian soldiers are stationed inside Bhutan and officials say they offer training to Bhutanese troops. Its military headquarters is in the western town of Haa, about 20km (12 miles) from Doklam.

While many Bhutanese are thankful to India for its assistance over the decades, others, particularly the young, want the country to chart its own course.

Bhutan has a population of just 800,000

Bhutan's foreign policy takes India's security concerns into account because of a special treaty, signed first in 1949. The treaty was revised in 2007, external but it gave Bhutan more freedom in areas of foreign policy and military purchases.

Some here feel India's influence has been overbearing and stifling.

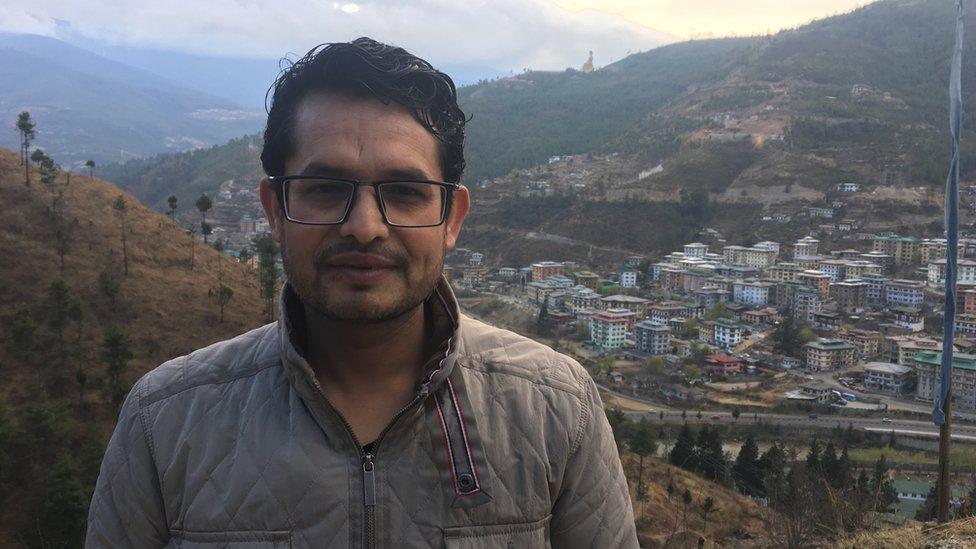

"As we mature [as a democracy] we have to get out of India's shadow. India also should not think of Bhutan as what some people refer to as a 'vassal state'. Let Bhutan decide its own political future," argues Gopilal Acharya, a writer and political analyst.

Bhutan and China have disputes over territory in the north and in the west. There is a growing feeling within Bhutan that it is time for the country to reach a settlement with China.

"Bhutan actually needs to resolve this issue with China at the earliest, that's what I feel. After that we may be able to move forward diplomatically or otherwise this [Doklam] problem is going to reoccur," says Karma Tenzin, a political commentator.

"We cannot afford to have two superpowers lock their horns at the doorstep of a peaceful nation like Bhutan."

Several people who I spoke with in Thimphu argue that India could have shown restraint and avoided a face-off with China.

They think India's stance might have an impact in Bhutan's efforts to solve its long-standing border dispute with Beijing.

Gopilal Acharya says Bhutan has to pull itself out from India's shadow

India has been unable to stop the Chinese making inroads into other south Asian countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Bangladesh. Bhutan is the only country in the region which has no formal diplomatic relations with Beijing.

There is also resentment among several Bhutanese who feel that India has been unfairly treating them in exploiting its natural resources. Delhi's "big brother" attitude, they say, could lead to people calling for more trade links with China. They point to Nepal playing the China card vis-à-vis its relations with India.

"For us, our future is with India. But we should forge a new kind of relationship which is equal between India and Bhutan. We have to look for new areas of engagement on equal footing," says Mr Acharya.

While India grapples with the challenge of a rising China, both militarily and economically, it is also in danger of losing its allies if its foreign policy is not based on mutual respect.

Bhutan may be a tiny Himalayan nation but it holds a strategic card. It does not want to be squeezed in India-China rivalry. The last thing they want to see is Chinese and Indian armies squaring up to each other once again near their border.

- Published26 January 2018

- Published5 July 2017