Malaysia's youth have power they won't use

- Published

When Malaysia goes to the polls next week, millennials could wield the most power at the ballot box. But what about the large number of young people who didn't even register? The BBC turned to the numbers - and the youth - to see if they understand and or even care about their influence.

Many young people in Malaysia simply wouldn't believe the influence they actually have.

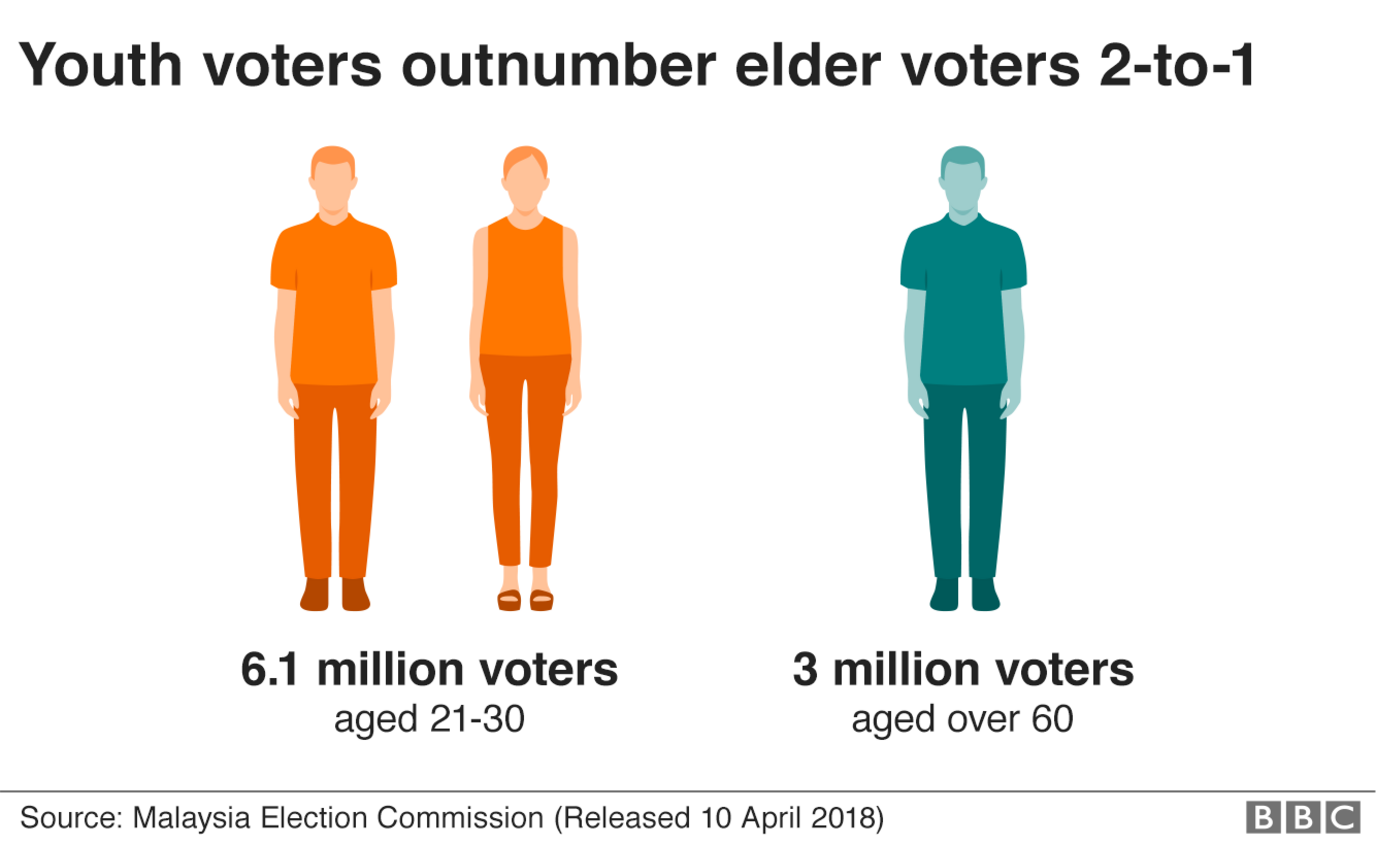

Of the 18.7 million registered voters in Malaysia as of the end of 2017, more than 40% are aged between 21 and 39, which is more than double the number of voters over 60.

Considering that 70% of Malaysian lawmakers are over 50 and that until recently Malaysian students at public universities weren't even allowed to get politically engaged, you might understand why this is a reluctant generation of voters.

But when voters go to the polls on 9 May that crucial group is now significantly larger than it was last election round, where they formed about 30% of the electorate.

It was during that election that the opposition made unprecedented gains by winning the popular vote despite ultimately failing to win enough seats to form a majority government, as Malaysia has a first-past-the-post or "simple majority" system.

It's a significant jump and one that the 64-year-old prime minister and president of ruling party Barisan Nasiona Najib Razak and the 92-year-old Mahathir Mohamed, former PM and leader of the opposition alliance, would do well to take note of.

The young make up a large proportion of Malaysia's population

For those studying Malaysia's demographic change, this is not a great surprise because in 2012 those aged between 15 and 29 were the largest generation in Malaysia. Five years on, the difference is that they can all vote now - as voting age is 21.

But the numbers of those who have chosen not to register might tell a different story. According to Malaysia's Election Commission, as many as 3.8m eligible voters did not register in time for this election - and two-thirds of them are in their 20s.

If this is genuine lack of interest, it is reflected in one poll by Merdeka Centre, an independent Malaysian polling organisation which last year looked at how young people in West Malaysia felt about politics.

They found that as many as 70% of them do not believe that their vote will bring about tangible changes in the government and don't think their elected representatives really care about people like them.

Young people felt disenfranchised and the high cost of living, low wages and unemployment didn't help matters.

"I don't know much but I only care a little bit because our economy sucks, there's inflation and I don't want to end up in poverty," 22-year-old student Alya Aziz told the BBC. Ms Aziz is one of those not registered to vote.

Leonie Leong, 27, told the BBC that she was keen to vote but registered too late for this election, admitting that registering was never high up on her to-do list.

"I know it's bad to think this way, that my vote won't count for anything other than the popular vote and the popular vote doesn't win anything."

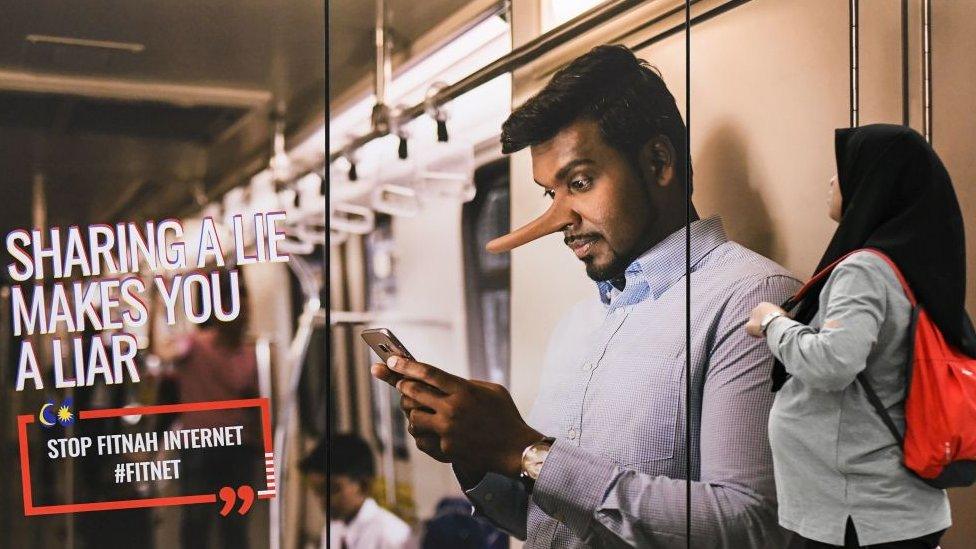

Another issue is that for many youth their knowledge and experience of politics is confined to social media: which they regard with a mixture of fascination and mistrust.

Low Chi-e, 25, also registered too late but says: "Based on my own experience, knowledge of politics for those who do not actively search for it is limited to social media, which in turn, is limited to those you choose to include in your social circle. In other words, if you know no one who cares about politics, you're susceptible to living under a rock".

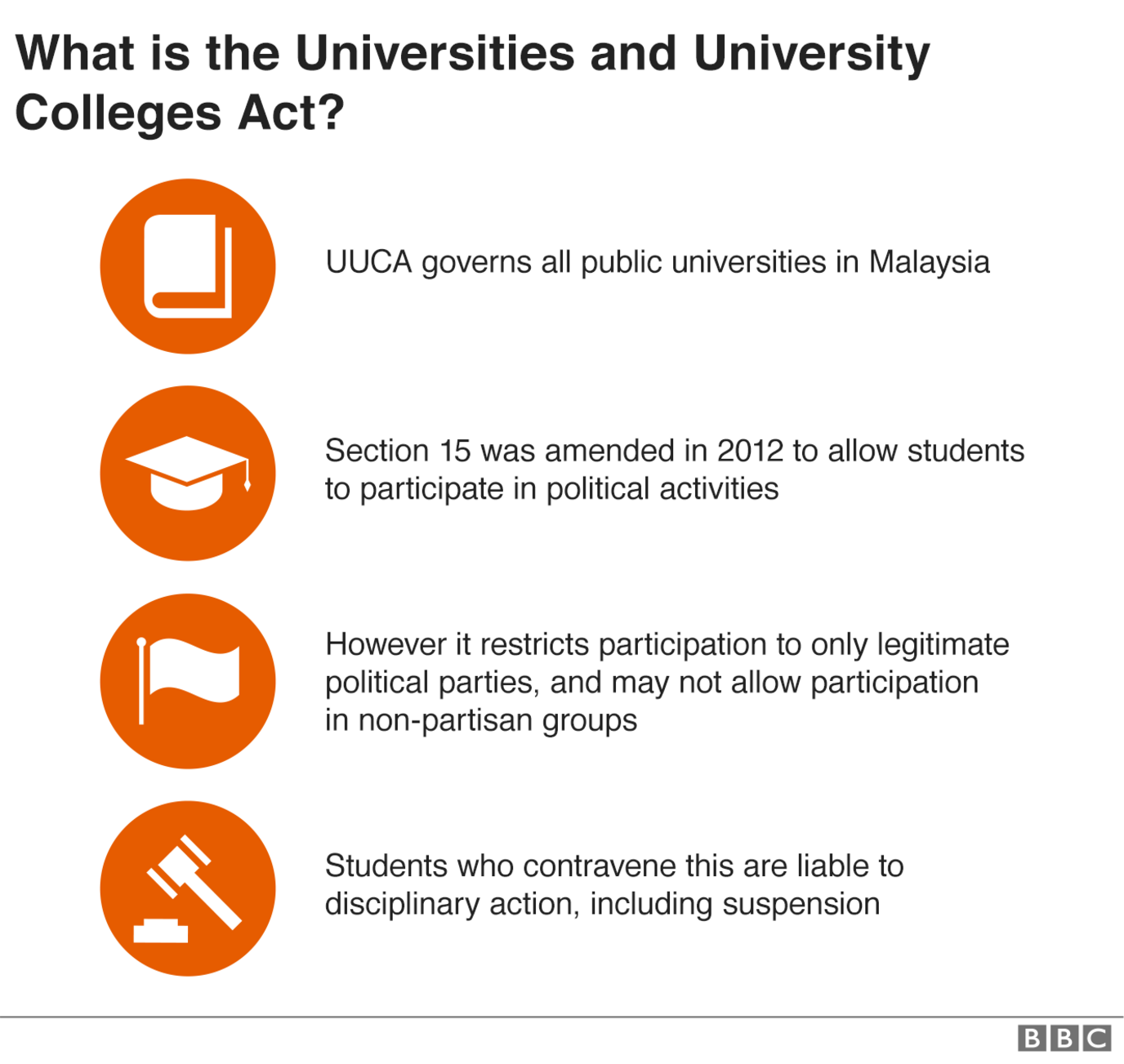

The Universities and University Colleges Act limits how much students can get involved in politics

Many analysts say this stems from a system that actively discourages youth from discussing politics, especially on university campuses.

At University Malaya, one of Malaysia's top public universities, for example, you wouldn't be able to tell that national elections are only days away.

Outside the university's gates, election fever is palpable with multicoloured flags lining the streets and fences - but on campus things are so quiet you wouldn't be able to tell elections are just days away.

Students at the university, such as Nur Hanifah, 22, and Nurul Syazwani, 23, say political discussions, or organisations, are a rarity on campus.

"Among students there are discussions but never in a formal setting, just amongst ourselves," Nur Hanifah says.

This is in part due to the Universities and University Colleges Act - legislation that governs all public universities in Malaysia.

The act is focused on outlining the administrative powers of universities - but, up until 2012, a clause prohibited public university students from participating in any form of political activity.

A set of amendments changed this, enabling students to participate in political activities so long as it is with a legitimate political party.

But observers say the amendment remains restrictive.

"Make no mistake...The amendments do not go far enough," lawyer Syahredzan Johan told the BBC.

"The law allows students to be involved and participate in political parties, but not organisations which the university deems to be 'detrimental to the interest of the University'. This is restrictive and undemocratic," he said, adding that such organisations could include grassroots bodies like Bersih, an electoral reform group.

Voon Zhen Yi, a research analyst at the Centre for Public Policy Studies, believes the rise of social media has in fact allowed students to directly engage with politicians and political groups.

"In the past if students wanted more information about politics, they would find it quite a challenge to get that."

He adds that although the age gap between voters and their elected representatives mean many feel disconnected, there is some cause for hope if only because campaigning is in full swing.

"Youth are getting quite interested because of the marketing, it's quite hard to escape election fever," he said.

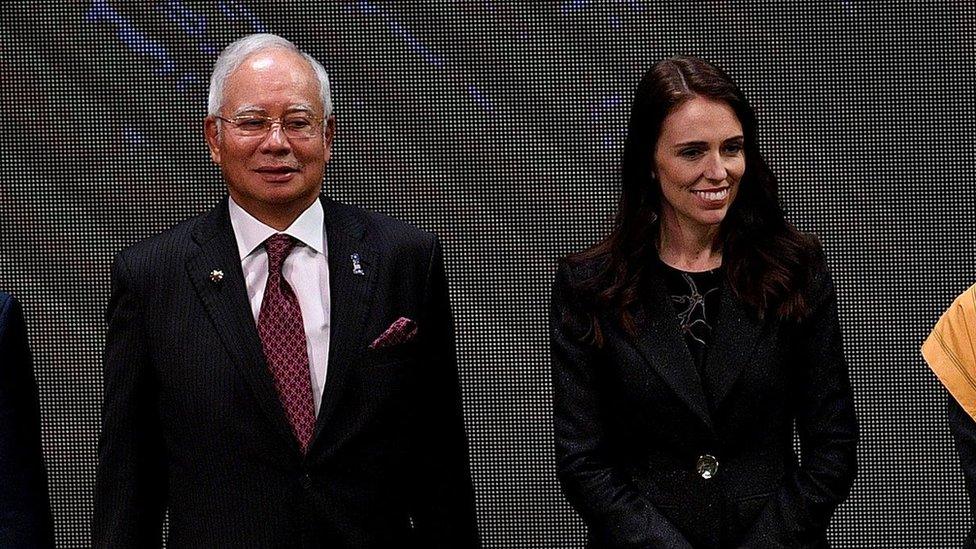

Malaysian PM Najib Razak, 64, and New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern, 37

Asmaliza Romlee, 32, says "because I'm older, I realise you have to vote because if you want country to change you must participate in the process".

But the realities of Malaysian politics, so strongly rooted in racial and religious agendas, just does not feel relevant to some young voters.

"I don't see any candidate that represents my beliefs about environmentalism, urban poverty, socio-economic issues, those kinds of things." Ms Asmaliza says.

"Overseas you have young leaders. In New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern is 37-years-old and in Canada they have Justin Trudeau. I hope to see all this in Malaysia in the next 10 years."

- Published26 March 2018