The other Balochistan: Six stories of life in a conflict zone

- Published

People in Balochistan's capital Quetta try to lead normal lives despite the threat of violence

Pakistan's poorest province, Balochistan, is often in the news because of targeted killings, suicide attacks and abductions. The BBC's Shumaila Jaffery met people in the capital Quetta trying to lead normal lives.

The secret life of a bank manager

Yasir is lead singer of underground rock band Malhaar. Bank manager by day but rocker by night, he must keep his passion for music hidden as he lives in a conservative Muslim society where it's taboo to sing and dance.

He and his friends gather in the evening in a basement room and play rock tunes to warm up but then get going with Bollywood songs. They're mostly students who use their spare cash to buy musical instruments and equipment.

"My customers at the bank wouldn't like it," says Yasir between takes. "I try not to share my music on my own social media accounts because I fear losing business."

Bank manager Yasir lives the rock'n'roll dream in his basement

As he strums his guitar to the tune of an Atif Aslam song, Yasir talks about his love of music.

"Our society is deeply wounded by the violence," he says. "Our purpose for playing music is to entertain people."

There's no public space for Malhaar to perform. They've been invited by universities in the past but their performances have been picketed by right-wing groups and have ended in scuffles.

"The environment is particularly tense for young people. They even have to be careful about how they dress," says Yasir.

Wearing "Western" clothes and not having a long beard can spell trouble.

Yasir knows there are no openings for musicians here but lives out his dreams in his basement rehearsal room.

"We just want to make people happy."

Life and death in her hands

Dr Shehla Sami Kakar was the first doctor who rushed towards the scene when a suicide bomber struck outside Quetta's civil hospital in August 2016.

Seventy people, mostly lawyers, were killed that day.

"There was a big pool of blood," she says. "Dozens of men in black coats and white shirts were lying on the floor."

Dr Shehla says her religious faith gives her strength

The gynaecologist says she didn't know what to do.

She now works in Quetta's Bolan Medical complex but suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the attack.

Dr Shehla says her religious faith helped her come through it.

"We have to live in this society," she says. "We survive with the hope every day that it's going to be a normal routine day."

She says all big cities in Pakistan have experienced violence, not just Quetta.

"When you look from the outside, it seems that we are leading very difficult lives," she says. "But I don't agree. It's the tribal mindset and lack of discipline in the city that bothers me the most."

She says women lack education and freedom in Balochistan.

"I am fully aware of the restrictions that male family members place on women, even for their medical treatment," she says. "The women don't have a complete say."

Quetta is home to many different languages and communities

But even with all these restrictions and complications, it's Balochistan's multi-ethnic makeup that challenges her the most.

"We have Hazara, Baloch, Pashtun, Punjabi, Urdu and Persian-speaking communities in Quetta," says Dr Shehla.

"All of them have different values and traditions so I have to consider their cultural sensitivities while treating them."

The journalist who faces being shot

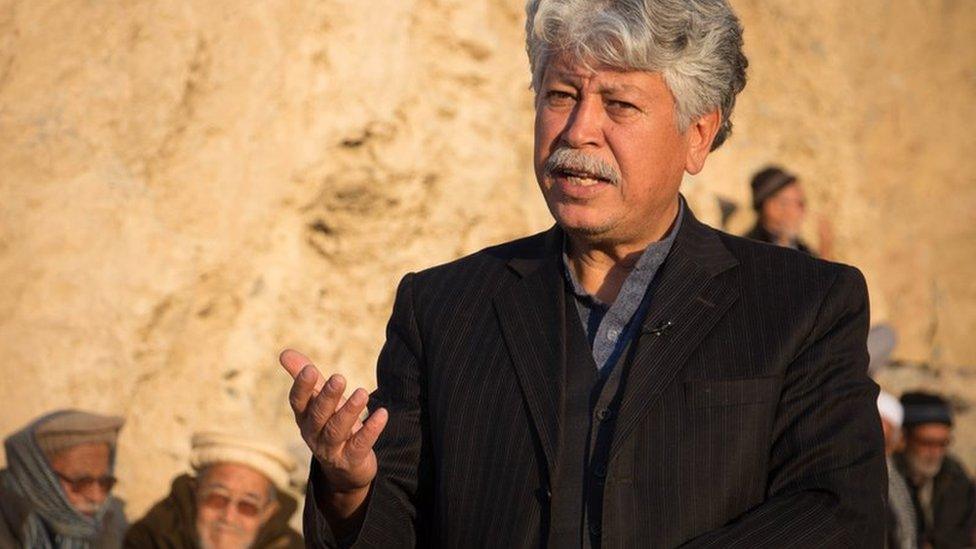

Khalil Ahmed is president of the Balochistan Union of Journalists. His office in the Quetta press club is surrounded by barbed wire and there are armed guards on duty.

He is matter of fact about the risks.

"Abduction is not a tradition here," he says. "You will be targeted, shot and silenced forever."

Thirty-eight journalists have been killed in Balochistan over the past decade.

Journalist Khalil Ahmed has long lived with the risks of reporting the news

They are targeted by the Taliban, al-Qaeda, Baloch separatists and sectarian organisations. There are also allegations of extra-judicial killings of reporters by the military and the state government, which officials deny.

As Khalil stands in the courtyard, students are holding a protest outside.

"You can only use a few limited words and cannot share your thoughts freely," he says.

Reflecting the viewpoint of Baloch separatists who oppose the Pakistani state also lands you in trouble. Eighteen journalists in the province are on trial under anti-terrorism laws for publishing such opinions.

Despite repeated promises by the government, these cases have not been thrown out yet.

"Separatists and militants tell us they have got all the information about our children and they can harm them at any time," says Khalil.

He's been a journalist for 18 years and refuses to give up.

"It's our job," he says. "The night we are destined to be in a grave cannot be changed, so why worry about it?"

Under the shadow of death

Naseem Javed is forced to live in a ghetto. As a Hazara and a Shia, he is in a minority. Hundreds of his people have lost their lives in targeted killings and suicide attacks over the past decade.

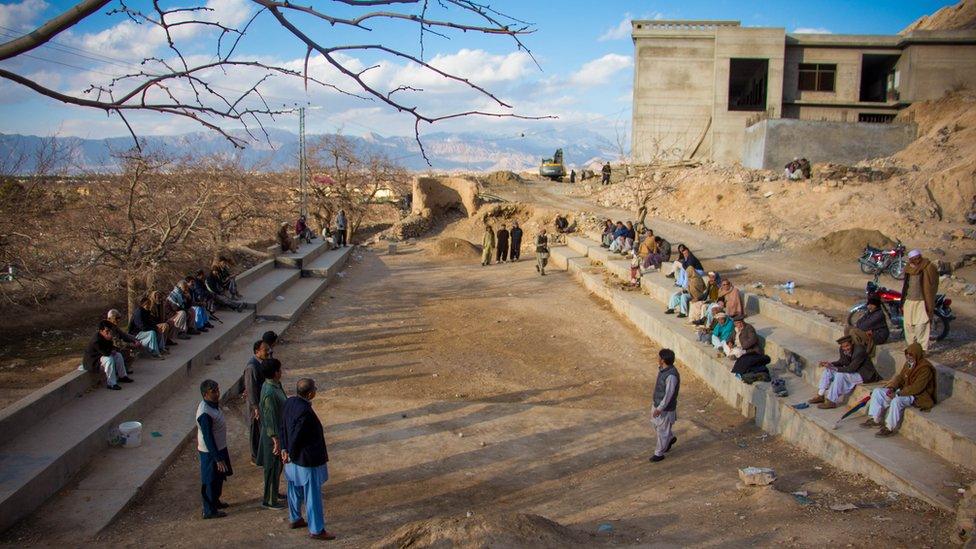

Haseem Javed seeks to learn from his Hazara elders

They have taken refuge in the Marriabad settlement overlooking Quetta. There is one entry point and it's manned by security personnel around the clock. But even this has not stopped the Hazara bloodshed.

"Cinema halls are destroyed, markets are closed, art galleries and theatres are in the ruins," says Naseem. "It's difficult to even breathe in this environment."

Men gather close to Qabristan-e-Shuhda, or the "martyrs' graveyard", on top of a small hill in the evening. They play a traditional game called "sang girag", or throw the stone.

As the men play, others sit in the fading sunlight and listen to recitations of religious poetry written in Persian.

Naseem Javed is young for the gathering but still visits.

Hazara men gather to recite Persian poetry and soak up the evening sun

"We are living under the shadow of death," he says.

"Those who can leave the country have already migrated. Youngsters feel that the future is bleak and have only one dream - to run away from this place."

He says their hopes are constantly raised when there is a lull in the violence, then dashed.

"People think that they might be able to lead normal lives but with another targeted killing they return to absolute despair," says Naseem, adding that they can only pray that things get better.

A student who hopes...

Journalism student Sehneela Manzoor, 23, is articulate, forthright and confident - and has no time to waste.

Sehneela Manzoor believes the world is her oyster if she works hard

"Things are improving," she says. "If I am sitting here and many of my friends and fellows are entering higher education and getting jobs, it shows that change is happening."

Of course, Sehneela, who studies at Balochistan University, is aware of the dangers - but she says she refuses to let them knock her off course.

"If something happens over and over again, people learn to live with it," she says.

But living where she does puts her at a disadvantage in her career, she admits.

"When we compare ourselves with students from other provinces, they are at a level where it's very hard to compete with them for job opportunities."

Sehneela believes the conservative tribal mindset is the biggest barrier to women's development.

But she's still hopeful, despite the fact young people are leaving Balochistan because they think their talent will be wasted.

"The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is here, new businesses are being set up, a lot of construction activity is going on and a new education system is being introduced."

She hopes to profit from it and help others stay and rebuild rather than move away.

The cobbler who may leave

Asmatullah Khan runs a shoe shop in Quetta's old town. His family has owned the shop since 1982 and he took it over after the death of his father.

It's all shipshape in Asmatullah Khan's shop but customers are hard to come by

"Customers are rare and business is bad," says Asmatullah, polishing a brown ladies sandal.

"Shopkeepers and customers used to be fearless without a care in the world."

Hashmi market was a favourite shopping destination for tourists from Punjab and Sindh provinces, as well as the families of military officers posted in Quetta.

But due to the rise in violence over the past decade, tourist numbers have collapsed and military families remain confined to barracks.

"We use to make about 90,000 Pakistani rupees [about $780; £580] a day, but now we earn about 10,000 rupees."

Tourists are reluctant to visit Quetta, far less venture into the old town

Asmatullah says that there are fewer attacks now but people's confidence is gone.

"Every morning when I leave home, my mother recites verses from the Koran so I come back safely," he says.

And the future is bleak.

"I cannot even meet basic needs of my children," says Asmatullah. "The quality of life has gone down drastically.

"If things don't improve, I will quit and go to Dubai as I don't have any other option."