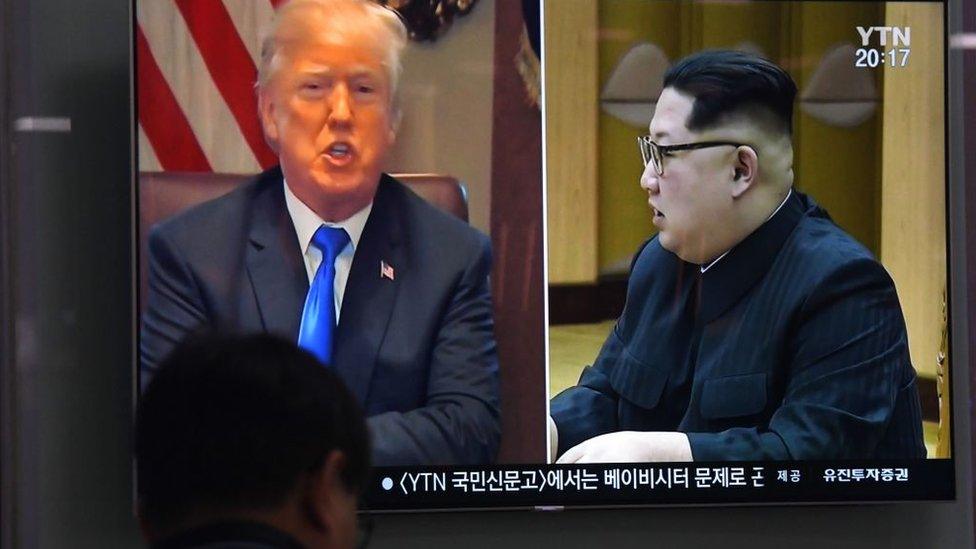

Kim Jong Un-Trump summit: How did it all fall apart?

- Published

Why did the carefully planned summit collapse?

President Donald Trump's shock announcement to cancel a planned summit with North Korea's Kim Jong-un follows weeks of fiery language. Analyst Ankit Panda looks at what happened.

In a letter released on Thursday morning, President Trump declared that the scheduled 12 June summit meeting in Singapore between him and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un - a meeting that would have been the first of its kind - would no longer take place.

Trump justified his decision based on the "tremendous anger and open hostility" shown in a statement released by North Korea's state-run Korean Central News Agency this week.

Choe Son-hui, a vice minister at North Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, called US Vice President Mike Pence a "political dummy" for repeating remarks Trump made a week earlier, threatening to attack Kim Jong-un if he didn't submit to a deal on the United States' terms at the meeting.

The story of the summit's collapse, however, ultimately began with Trump's national security adviser, John Bolton, who had worked to raise expectations for what concessions the US should expect from North Korea to stratospheric levels.

Mr Bolton had built a maximalist "denuclearization" objective, seeking a deal at the Singapore meeting that would see North Korea turn over all its weapons of mass destruction - not only its nuclear weapons, but also its chemical and biological weapons.

Why North Korea is angry at this man

But Mr Bolton was probably never sincerely interested in seeing a diplomatic process with North Korea succeed.

Weeks before becoming President Trump's national security adviser, John Bolton, as a then-private citizen, said in the aftermath of the president's acceptance of Kim Jong-un's invitation to meet that the goal of the process would be to "foreshorten the amount of time that we're going to waste in negotiations that will never produce the result we want".

His maximalist conception of what the United States should seek came to be known as the 'Libya model,' after the 2003 disarmament process that saw late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi deprived of his nascent nuclear program. North Korea has long dreaded any comparisons to Libya and has said as much in recent statements.

Protesters toppled Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011

Ms Choe's statement lashed out against the comparison to Libya, noting that North Korea was a full-fledged nuclear power, with intercontinental-range ballistic missiles and thermonuclear weapons to mount on them.

Libya meanwhile was a fledgling nuclear pariah state that had "simply installed a few items of equipment and fiddled around with them."

The moment the summit became doomed was when President Trump, speaking off the cuff, confused the 2003 "Libya model" of disarmament with the 2011 US-led intervention in Libya - a move that led directly to the demise of Muammar Gaddafi.

This is what Kim Jong-un learned from Libya's experience: that agreeing to disarm at the behest of the United States will sooner or later lead to his end.

The US has tens of thousands of troops in South Korea

North Korea effectively saw Trump's comment as a threat. US Vice-President Mike Pence's decision to support Mr Trump's interpretation in a separate interview made it appear as if the president's off-the-cuff comment was a considered a US policy position - that should Kim come to Singapore and do anything other than submit to US demands, he would face US military action.

The Trump administration has, by all accounts, failed to take what North Korea has said about its negotiating position seriously. Even before Ms Choe's statement - the one that, according to Mr Trump's own letter, brought down the summit - North Korea communicated its displeasure with the US over John Bolton's rhetoric and over plans by the US and South Korea to conduct an aerial military exercise involving nuclear-capable bombers, something Pyongyang has long viewed as threatening.

(If the message wasn't clear, North Korean officials reportedly stood up their US counterparts, external at a planning meeting in Singapore earlier this month.)

The US has angered North Korea with aerial exercises over the peninsula before

More seriously, a statement by the Trump administration that Washington paid no costs and made no concessions in the run-up to the cancellation of this summit is false. The president's decision to cancel the summit appears to have blindsided Seoul, stressing an important US alliance at a pivotal time.

Secondly, the decision to cancel the summit just hours after North Korea apparently carried through with its decision to dismantle its nuclear testing site creates unfavourable international optics.

Washington comes off as the recalcitrant party, willing to scuttle a promising diplomatic process over nothing more than a harshly worded statement from a North Korean Foreign Ministry official.

A satellite image of the Punggye-ri site before it was reportedly destroyed

Looking ahead, there's a real possibility that President Trump will choose to blame the North Koreans for duplicity - for pulling the rug out from under him and his chances of a Nobel Peace Prize.

North Korea's negotiating position never changed; it didn't change after Mr Kim's two meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping and it didn't change after the inter-Korean summit meeting on 27 April.

President Trump's letter appears to leave open an avenue for Kim Jong-un to work with him to restore the summit. He ends with an invitation for the North Korean leader, whom he addressed collegially as "His Excellency," to not hesitate to "call me or write".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Kim won't be eager to take up the president on his offer. While North Korea had much to gain from the summit, it has probably become apparent for Pyongyang that should it choose to meet Donald Trump, it would have little idea of what to expect.

That assumption would appear to be well-founded; the administration does not have a clear idea of what it seeks out of high-stakes diplomacy with North Korea.

Ankit Panda is an adjunct senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists and a senior editor at The Diplomat.

- Published24 May 2018

- Published24 May 2018

- Published24 May 2018