Trump-Kim North Korea summit: What just happened?

- Published

Are they back to yelling at each other again?

US President Donald Trump has just cancelled what would have been a historic summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

The shock move could undo months of diplomatic effort and throws the future of the Korean peninsula back into doubt.

What just happened?

The 12 June meeting was supposed to discuss ways of reducing the nuclear threat on the Korean peninsula. It would have been historic - the first time a sitting US president had met their North Korean counterpart.

Trump: "US military is ready if necessary"

Past days, though, had seen increasing hostility and a certain lack of diplomatic courtesy from both sides, casting doubt over whether the summit would go ahead.

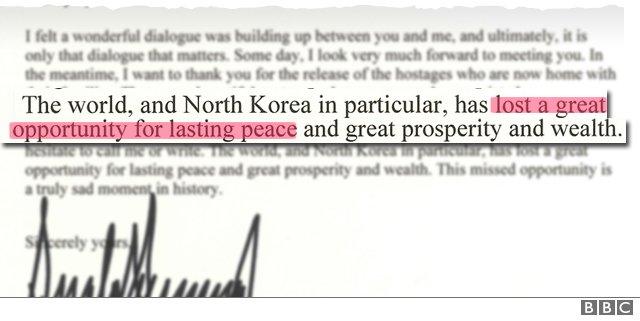

On Thursday, Mr Trump sent a letter to Mr Kim saying that he wouldn't be going. He blamed North Korea's "tremendous anger and open hostility".

While both Washington and Pyongyang have said there is still a chance for talks at a later stage, they have also brought back aggressive military threats against the other.

How did we get here?

Last year saw seen tensions between North Korea and the US reach worrying levels, with threats of mutual nuclear destruction and petty name calling. North Korea carried out its largest ever nuclear weapon test and repeatedly fired off missiles.

1 January 2018 brought an unexpected turn, when Kim Jong-un reached out to South Korea.

After lots of careful negotiations, North Korea took part in the Winter Olympics in the South, and Mr Kim said he was willing to sit down with the US to talk denuclearisation.

What followed was a historic meeting between North and South Korea where they agreed to end hostilities and work together towards denuclearisation.

The moment Kim Jong-un crossed into South Korea

The world eagerly awaited the next event: direct talks between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un. That was finally confirmed two weeks ago.

In the run-up North Korea released three US detainees and blew up its nuclear testing site as gestures of good intent.

Where did it all go wrong?

After the initial enthusiasm though, the actual preparations for the summit proved to be - predictably - difficult.

The nuclear word Trump and Kim can't agree on

While the stated goal was denuclearisation, it soon became clear that Pyongyang and Washington were not exactly on the same page over what that meant.

For the US it appeared to mean complete and irreversible dismantling of the North's nuclear programme and weapons, allowing international inspectors to check every step of that process, before any talk of sanctions being lifted.

For North Korea, it meant a much more reciprocal progress. If Pyongyang was to give up its nuclear asset, it wanted to see similar gestures from Washington.

The US has a large military presence in South Korea and in Japan - both of which North Korea would expect to be scaled down, along with assurances that its survival as a state would never be in question.

What has Libya to do with it?

Pyongyang has for years wanted to be accepted as an equal nuclear power. Once it appeared to have mastered nuclear technology and antiballistic missiles, it wanted that fact to be reflected in the negotiations.

But top US diplomats have repeatedly brought up the one example for denuclearisation that North Korea least wants to hear about: Libya.

There, former leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi gave up his nuclear programme only for him to be brutally lynched and killed by Western-backed rebels a few years later.

The Libya model was first mentioned by US National Security Advisor John Bolton, and then - despite strong North Korean outrage at Bolton - again by Vice-President Mike Pence.

Why North Korea is angry at this man: John Bolton

In reaction to Mr Pence's comments, Pyongyang slammed the VP a "dummy" and his remarks "stupid", threatening that a nuclear showdown was the alternative to talks.

And in reaction to that, the US axed the summit.

So what now?

While the US says there's still a backdoor open for talks and North Korea has expressed similar sentiment, both sides have also brought back the big rhetorical guns.

Mr Trump warned the North of the "massive and powerful" nuclear capabilities of the US, adding: "I pray to God they will never have to be used."

Pyongyang has already said a "nuclear-to-nuclear showdown" was the alternative to the summit and so the situation seems to be back where it was in 2017 when the Trump-Kim relationship was marked by an escalating string of insults and threats of mutual destruction.

With one failed summit down, military conflict might still be unlikely - but it seems a lot less unlikely than when the talks were still on.

- Published24 May 2018

- Published24 May 2018

- Published21 April 2020

- Published24 May 2018