Kim Jong-un: The new kid on the diplomatic block

- Published

Are we witnessing the making of Kim Jong-un as a new international statesman?

Kim Jong-un has suddenly become the new popular leader in the political class of 2018.

After years in isolation, he has emerged as a powerful player. Leaders from China, Russia, Syria, South Korea and the US have all met or are due to meet Mr Kim this year.

They are literally lining up. Vladimir Putin has just extended an invitation for him to come to Vladivostock in September and Syria's President Assad has said he would also like to visit Pyongyang.

"We are witnessing the making of 'Kim Jong-un, international statesman'," said Jean Lee, the former Associated Press bureau chief in Pyongyang. "This is such a different international debut than we saw in 2010, when Kim Jong-un stepped forward as the unknown, baby-faced heir apparent.

"Now, with a proven intercontinental ballistic missile under his belt, Kim is stepping out as the leader of a country that sees itself as a nuclear power on par with the world's other nuclear powers, including the United States. "

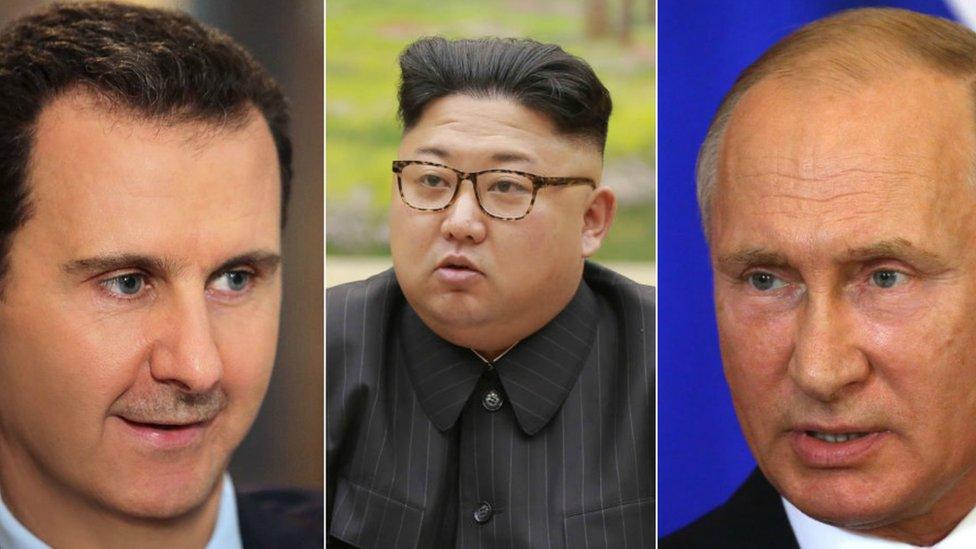

Both President Assad (L) and Putin (R) have expressed interest in meeting Mr Kim (C)

This is of course the kind of prize he was looking for when he accelerated his missile testing programme in 2017, as Ken Gause, the author of North Korean House of Cards, points out in a recent essay, external.

"Kim Jong-un most likely came to the conclusion that the only way to ensure success on the diplomatic front was to escalate to de-escalate… North Korea would have to force its way to the negotiating table from a position of strength. "

But little did Kim Jong-un know he was going to get THE prize. A summit with the US president. It gave him the diplomatic street cred he was hoping for. And it also offered him an opportunity to say North Korea was open for business.

"Kim has kept himself at arm's length with the outside world for such a long time that foreign officials do tend to jump at the chance to meet him, if only to gain insight into who he is and what he wants for his country," says Jean Lee.

And jump they have.

Catching the travel bug

Two things helped Kim Jong-un's new diplomatic outreach. South Korea elected a liberal president who campaigned with the promise to engage with North Korea. This allowed him to establish a relationship with his neighbour.

Then came the invitation to the US president. Previous commanders-in-chief had wanted some kind of guarantees in place before a summit.

But not Donald Trump. The unpredictable US president who'd spent a year threatening Pyongyang with a pre-emptive strike made a snap decision to agree to face to face talks.

Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un: From enemies to frenemies

When Mr Kim walks out to greet Donald Trump in Singapore, it's worth remembering that in just six months he has gone from complete international isolation to being one of two leaders at the centre of one the world's biggest geo-political dramas.

The summit itself has given Kim Jong-un political leverage.

This new diplomatic strategy does not just arise from a position of strength, but also out of necessity.

Having declared that his weapons programme was complete, Mr Kim announced that his main focus would be on the economy. To do that he needed to forge alliances and rebuild old friendships.

First stop was, of course, China, North Korea's main trading partner. President Xi Jinping helped enforce Donald Trump's maximum pressure strategy at the end of 2017, cutting off vital supplies much to the disgust of Pyongyang. The state even turned away a Chinese envoy when he tried to visit at the end of last year.

Mr Kim and Mr Xi were pictured together in an intimate setting

But now Kim Jong-un has caught the travel bug. Two visits to China in under two months. First to Beijing and then to Dalian in early May where he took a stroll along the beach with President Xi and apparently talked trade.

It had echoes of his historic meeting in April at the Korean border with the South Korean President Moon Jae-in. Just friends taking a walk, talking about the future of their two countries. Kim Jong-un has looked willing to engage in a way his father and grandfather never were.

Mr Moon and Mr Kim embraced as the world looked on

It's worth noting the timing of his China trips. Each visit was made just days before Mr Kim met the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. A cunning strategic move which may have allowed him to play one off against the other.

China is in favour of a slower approach to denuclearisation and would prefer sanctions to be lifted to keep North Korea's economy stable.

Mr Kim can turn around to the US and say - look who I've got in my corner.

New plans and old alliances

He made a similar move using Moscow as leverage just last week. Former North Korean spy chief Kim Yong-chol was on his way to the United States with his leader's rather large letter, when Kim Jong-un decided now was the time to welcome the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to Pyongyang.

It was the first visit by a senior Russian diplomat in over a decade. It may of course have been a coincidence, but Donald Trump wasn't happy about it.

Mr Lavrov's visit was the first by a senior Russian diplomat in over a decade

"I didn't like the Russian meeting. I said what's the purpose of the Russian meeting? If it's a positive meeting, I love it. If it's a negative meeting, I'm not happy," he told reporters.

He may have good reason not to be happy. Russia views itself as an alternative moderator in any denuclearisation discussions. It shares a border with North Korea and key economic interests.

So if Washington thought North Korea was trapped in a corner, Kim Jong-un was sending them a message and parading his other options.

Adam Mount from the Federation of American Scientists told me: "Each new relationship provides leverage against American efforts to pressure the regime. Outreach to Beijing has made sanctions relief a virtual certainty, especially given that the Trump team has positioned itself as the one endangering a peace process.

"Growing indications of an alignment with Moscow are particularly worrisome. If they continue to expand, they could afford Pyongyang a variety of ways to break out of containment in the future."

It wasn't too long ago that Mr Kim was testing nuclear missiles

Syrian President Bashar-al Assad's relationship with Pyongyang is one that may also worry the US and the UN.

The North's state-run media agency said that he plans to make a visit to Pyongyang.

It is an old alliance. The North established diplomatic relations with Syria in 1966 and sent troops and weapons to the country during the Arab-Israeli war in October 1973.

A UN report leaked in February accused the North of making 40 shipments to Syria between 2012 and 2017 of materials including acid-resistant tiles, valves and pipes that could be used to make chemical weapons.

The international community will be now watching this particular alliance even more carefully.

Whiff of desperation?

But not everything has gone North Korea's way.

Pyongyang's vice-foreign minister last month issued a harsh statement which criticised US Vice-President Mike Pence as "stupid" and warned the United States that it faced a nuclear showdown if diplomacy failed.

Most on the Korean peninsula know this is typical North Korean rhetoric and the South Korean administration has been very careful not to react to similar swipes.

It was also perhaps utterly predictable after Mr Pence and National Security Adviser John Bolton both compared nuclear disarmament in North Korea to Libya.

But the words rattled the White House. It gave Donald Trump ammunition to walk away and cancel the summit. I heard so many analysts from Washington on that night as I reported from Seoul wondering if Pyongyang would go on the offensive, maybe even test another missile.

They didn't. Instead they attempted to take the moral high ground. There was a hastily arranged meeting with President Moon at the border to smooth things over with the South.

Kim Jong-un hugged his neighbour - a gesture designed perhaps to portray a gentler side. He then despatched his right hand man to New York to try to get things back on track and wrote President Trump that now famous letter.

US-North Korea: Trump gets an unusually large letter

Some may have felt there was a whiff of desperation from the North Korean leader. Perhaps he seemed a little too eager to save his prized summit which he saw slipping away.

But luckily for him, it paled in comparison to the daily dramas of the White House. And many wondered if Donald Trump really knew what he was doing. As sociologist Aidan Foster Carter tweeted:

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Kim Jong-un has changed the rules of the game. Last year his nuclear arsenal was a liability, now he has turned them into a diplomatic tool.

But what is North Korea's end game? And what happens after the summit?

Former US state department official Joel Wit, who also founded the North Korea analysis site 38North, told a press briefing: "This isn't a 'charm offensive', this isn't a sort of tactical trick. There is enormous momentum in Pyongyang behind what they're doing. I personally don't think it's because of sanctions.

"That may have played a small role. But it's something they decided internally and it has to do with the size of their nuclear arsenal, the missiles, the desire for modernization of their economy. All of these different issues have sort of come together at this moment.

"And I think what you need to do is pay attention to what the North Koreans are saying. It's not just propaganda. He doesn't just say things. This is a new formulation that is very important."

- Published29 May 2018

- Published5 June 2018

- Published14 April 2018

- Published21 April 2020

- Published11 September 2023