Uzbekistan: Land of a thousand shrines

- Published

Uzbekistan boasts hundreds of holy places and shrines attracting pilgrims from home and abroad

Uzbekistan has aspirations to become a second Mecca, a destination for pilgrims from all over the world.

Central Asia's most populous country boasts a wealth of well-preserved mosques and shrines in famous silk road cities like Samarkand and Bukhara.

For millions of Uzbeks these are sacred places. But for the Uzbek government they also represent an opportunity to boost tourism as the country opens up after decades of isolationist, authoritarian rule.

Samarkand is home to dozens of magnificent tombs. Notable figures like the emperor Tamerlane, the astronomer Ulughbek and Kusam Ibn Abbas, the cousin of the Prophet Muhammad, who brought Islam to this land in the 7th Century, are all buried here.

Some of the most famous religious leaders and scientists are buried in Samarkand

But there is one grave that is unlike any other. Every morning hundreds of people climb a hilltop on the outskirts of the city to visit an oddly shaped, elongated tomb, surrounded by pistachio and apricot trees among the ruins of the old city.

The air is filled with birdsong and the murmur of prayers. Families share lunch on the benches and young couples take selfies nearby.

But among the pilgrims are not just Muslims, because this tomb is believed to be the last resting place of the biblical prophet Daniel, or Daniyar as Uzbeks call him.

"Muslims, Christians and Jews come here and say their prayers according their own religion," Firdovsi, a young guide explains. "St Daniel was a Jew but our Muslims respect him as he was the prophet of Allah."

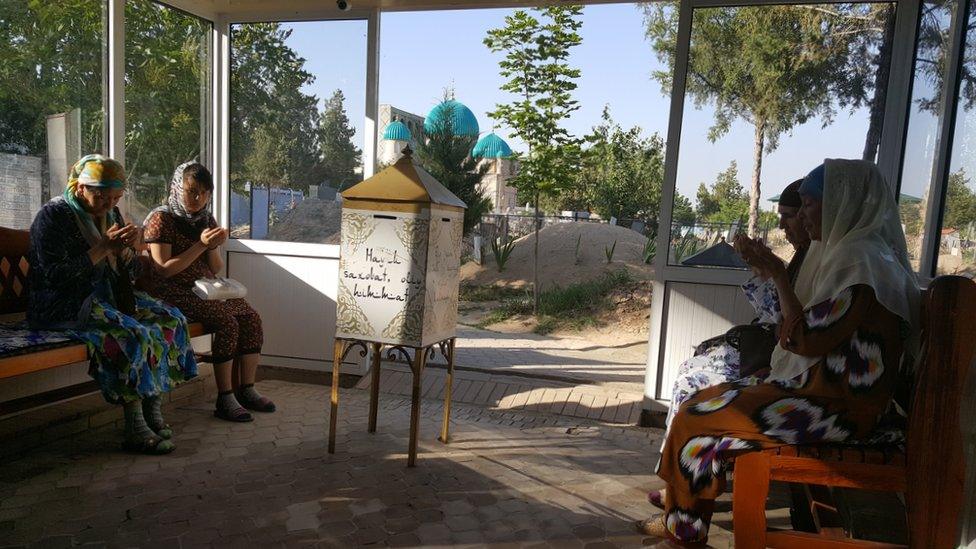

Uzbekistan is a predominantly Muslim country and most of the visitors to shrines are locals

Dilrabo (centre) and her daughter and granddaughter travelled to pray at the Daniyar shrine

"I often come here and pray for his soul," a woman called Dilrabo tells me. "He was not only a Jewish prophet, he was sent to all humanity. I even called my grandson Daniyar in his honour."

Dilrabo has come with her daughter Setora and a granddaughter. After prayers led by a mullah they join the queue to take a closer look at the tomb.

It's an extraordinary edifice, more than 20m (65ft) long and made from sand-coloured bricks in the medieval Islamic style with internal arches and a domed ceiling.

Inside the mausoleum or maqbarah, there is an 18m long sarcophagus covered in dark green velvet cloth embroidered in gold with verses from the holy Koran.

The pilgrimage ends with every visitor touching the centuries old pistachio tree outside and making a wish

This place is one of just a few in the world where people from different faiths come together to worship.

"I'm a Jew and if I want I can pray here and a Christian can pray here as well," Suzanne from Israel says. "This is all about Uzbek tolerance. This place unites people."

Kristina from Moscow tells me that her friends came from Russia to ask for healing from an illness. "They are cured now," she says.

Believing in magic or the healing powers of the saints or sacred places is a deep-rooted tradition in Uzbekistan - and pilgrimages to shrines go back thousands of years to Shaman, Buddhist or Zoroastrian times.

Even over 1,200 years of Islamic presence have not erased these ancient traditions as people simply mixed their old beliefs with the Muslim faith. No wonder then that places like Daniel's tomb are full of legends.

There are various stories explaining the length of the Daniyar sarcophagus

As to why the tomb is 18m long: Many people believe that St Daniel was either a very tall man or his tomb grows a little every year.

Uzbekistan boasts hundreds of shrines across the country, many of which were neglected or closed during the time of the Soviet Union.

"Central Asian Islam is quite flexible, inclusive and mixed with local traditions," Khurshid Yuldoshev, a former religious school student says. "That's why religion is interpreted more tolerantly. The tradition of visiting shrines is benign and part of our culture and has nothing to do with political Islam; these pilgrims are peaceful."

Women praying at the popular Zangi-ota shrine near the capital Tashkent

Political Islam has been something the Uzbek government has long feared. Under the 26-year rule of the late autocratic President Islam Karimov, thousands of independent Muslims were jailed.

Now Uzbekistan says it is changing.

Current President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who came to power after Karimov's death in 2016, promised more religious freedom.

"The government is releasing those who have truly repented," says Shoazim Minvarov, the head of the newly founded Centre of Islamic Civilisation in the capital Tashkent.

Mr Minovarv believes that Uzbeks who lived in the atheist Soviet Union lacked knowledge and orientation once communism disappeared.

During the 1990s hundreds of disillusioned young Uzbeks joined the Taliban and al-Qaeda affiliated organisations.

Now the authorities hope that a renewed emphasis on local religious traditions will counteract extreme beliefs.

"Radicalism is the consequence of ignorance," Mr Minovarov says. "We want to teach our people the Islam of enlightenment."

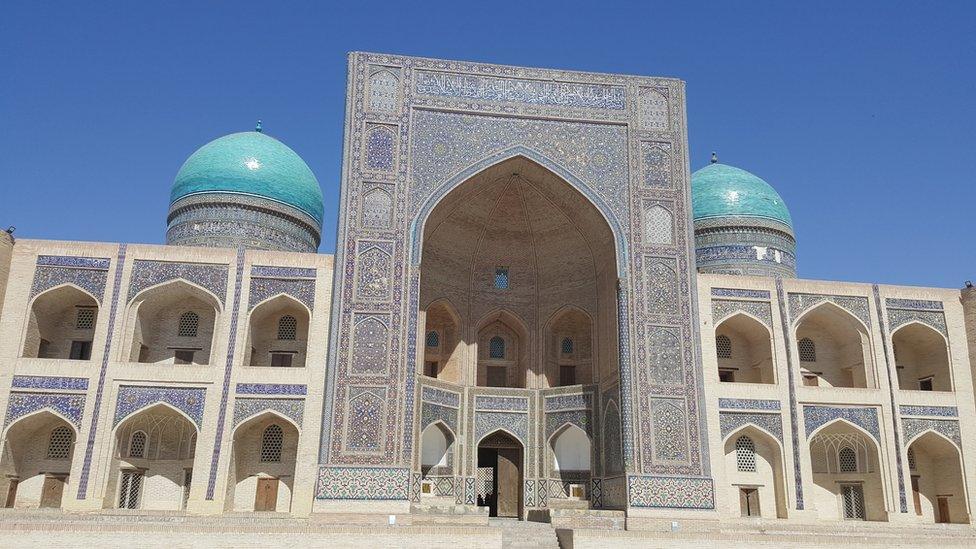

The famous Silk Road city of Bukhara has many mosques and shrines

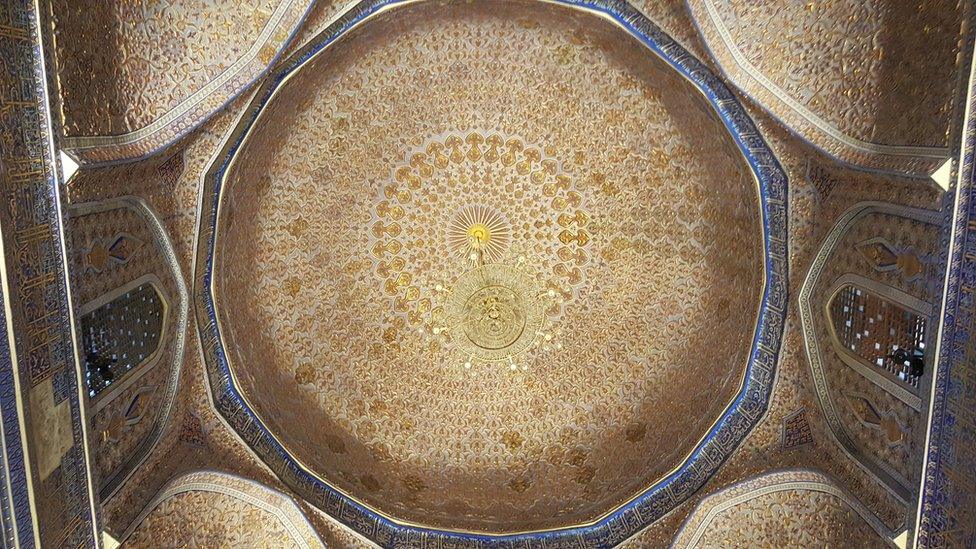

The magnificent ceiling in Tamerlane's tomb, Gur Emir

No one knows for sure how many shrines there are in Uzbekistan. Some officials put the number at around 2,000. And this wealth is an opportunity for the government to boost tourism.

"Only last year, nearly 9 million Uzbek citizens performed a pilgrimage," says Abdulaziz Aqqulov, the deputy head of the Uzbekistan Tourism Committee.

The number of foreign tourists still lags behind with around two million visitors a year, but Uzbekistan has now opened its borders to neighbouring countries and eased visa restrictions for many others.

"World famous Islamic scientists and scholars like Imam al-Bukhari or Bahauddin Naqshband are buried in Uzbekistan," Mr Aqqulov says. "Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Turkey or India can provide millions of additional pilgrims to these sites."

The potential is indeed significant. The 14th Century Sufi leader Bahauddin Naqshband alone is believed to have more than 100 million followers worldwide, representing a huge number of potential pilgrims to his tomb in the ancient Uzbek city of Bukhara.

For now, the bulk of visitors are from Uzbekistan itself.

At the St Daniel's shrine in Samarkand, Dilrabo and her daughter have completed their pilgrimage under the curious eyes of Setora's little daughter.

Once the adults have finished, the girl leaves her sweets on a bench and goes up to the old pistachio tree herself to share a whispered wish.

All pictures BBC

- Published30 October 2024