Kem Sokha: Jailed for standing up to Cambodia's strongman

- Published

Kem Sokha came close to victory in 2013

The Cambodian ruling party's landslide win in recent elections came as little surprise - the widespread jailing of rivals meant there was almost no political opposition left. The most prominent of them remains in prison, with no immediate prospect of release, as George Wright reports.

In the early hours of Sunday 3 September last year, Kem Monovithya, a politician and daughter of opposition leader Kem Sokha, received a call from her parents - armed police were attempting to break into their family home in the capital Phnom Penh.

"My mum said there's more than 100 people trying to break into our house," Monovithya said in an interview last month.

They had no warrant, but with their guards being held at gunpoint, her father decided it would be safer to open the door.

"He told me he had to get off the phone because 'they are going to handcuff me'," she recalls.

Then the phone went dead.

Kem Sokha was jailed and a year on, has never gone on trial. He remains in solitary confinement in a remote prison near the Vietnamese border.

Cynical move?

In the 2013 elections, Sokha and Sam Rainsy had brought their Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) to within just seven seats of victory, despite accusations of vote-rigging and intimidation.

Rainsy, a long-time foe of Prime Minister Hun Sen, has been living in Paris since 2015 to avoid jail over convictions widely branded as politically motivated.

So as the next election approached, Sokha was the only viable threat to the prime minister's 33-year iron-fisted rule.

CNRP supporters prepare a banner calling for his release

Sokha was accused of plotting to wage a US-backed revolution. This was based upon a 2013 video where Sokha was seen telling an audience in Australia that he had been receiving political support and advice from the US.

However, many saw it as a cynical move, aimed at securing victory for the ruling Cambodian People's Party (CPP).

The CNRP was outlawed in November, allowing the CPP to win all 125 National Assembly seats on 29 July, making Cambodia a de facto one-party state.

Sokha's arrest marked an alarming escalation in an already deteriorating political climate that had seen rights advocates, opposition supporters and critics jailed.

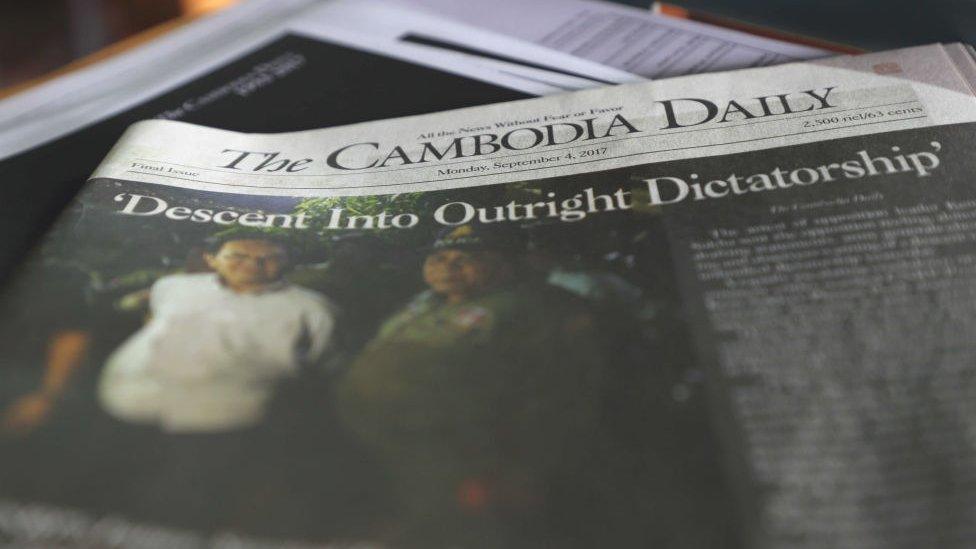

A copy of the final issue of the Cambodia Daily

On the day of his arrest, the Cambodia Daily published its last ever newspaper as it was shut down in a crackdown on independent media. It ran a front page headline "Descent Into Outright Dictatorship" above a photo of a startled Sokha in handcuffs.

'Completely traumatised'

For the past year, the only people who have been allowed to visit Sokha are his wife, Te Chanmono, and lawyers. The government has rejected repeated requests for visits from international observers, UN officials, foreign diplomats and human rights officers.

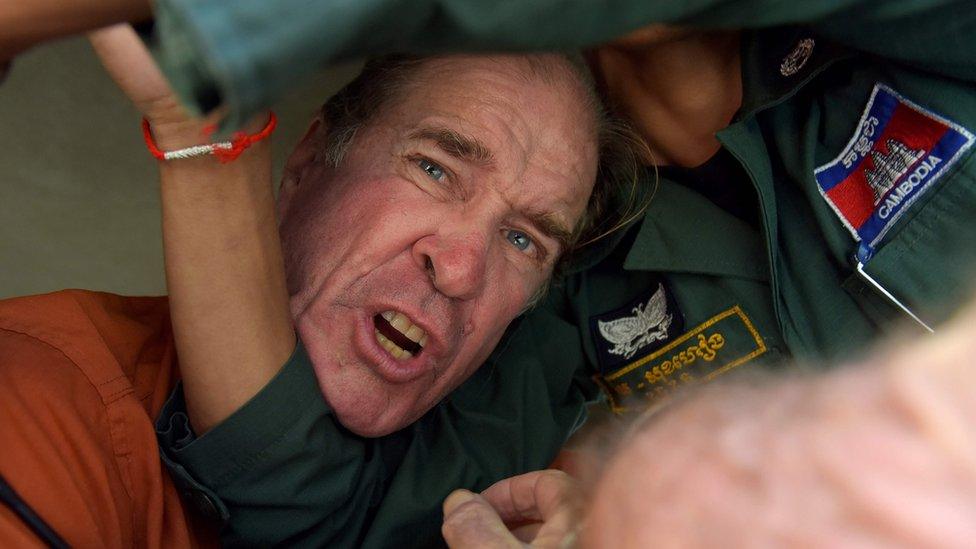

Kem Sokha is shown here escorted by police in 2017

Sokha spends most of his days alone and prison guards generally do not converse with him, Monovithya says. Chanmono was only recently allowed to bring him books, mostly relating to Buddhist meditation, but he is still banned from using pens and pencils, she adds.

One of Sokha's lawyers, Heng Pheng, who visits his client every few weeks, says he attempts to stay active and is allowed to grow vegetables but his moods are up and down, often due to his serious health problems. He currently is suffering from high blood pressure, severe pain in his shoulder and diabetes but is being denied surgery and other medical treatment.

Monovithya says the family home in Phnom Penh is also under regular surveillance and her mother is "completely traumatised".

"I think it's more difficult on her psychologically than any of us."

Hun Sen has been known to ramp up oppression during politically tense periods before relieving the pressure valve once he has stamped his authority once more.

So with the election done and dusted, some observers were expecting Sokha to be released on bail.

Almost all the other detained CNRP members were recently free but, last week, Phnom Penh Municipal Court extended Sokha's pre-trial detention for a further six months.

This came a day after Hun Sen told around 10,000 garment workers that he would keep the opposition leader locked up, which appeared to once again contradict his claims that the country's judiciary is independent.

PM Hun Sen has not backed down on Kem Sokha's detention

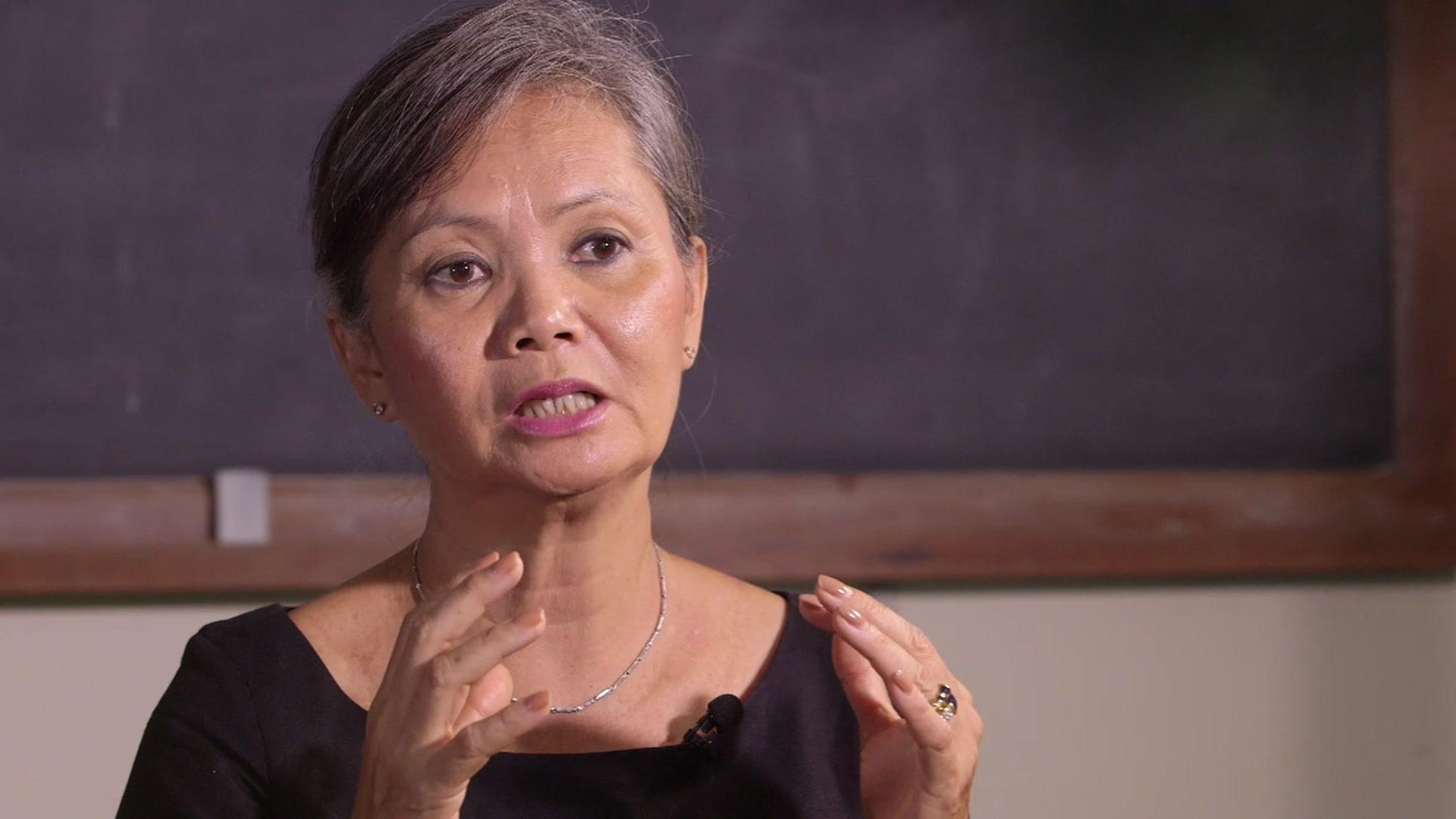

Astrid Noren-Nilsson, an associate senior lecturer at Sweden's Lund University specialising in Cambodian politics, says the decision to keep Sokha locked up illustrates that the ruling party will not be relaxing its heavy-handed approach to the CNRP.

"The election marks a transition to a new, one-party order, and the government needs to establish the 'new normal'," she argues.

She says the international community could press for Sokha's release by making credible threats to Cambodia's economy.

Cambodia generated more than $7bn (£5.4bn) from exporting garment and footwear products last year. The main importer is the EU, which allows Cambodia duty-free access under the Everything But Arms agreement, on the condition that democratic and human rights standards are met.

The EU has said it could consider taking action against Cambodia if the political situation does not improve.

While there was never much hope that the CNRP could contest the election, she says, "the release of Kem Sokha could be a minor enough concession".

'Not a decent person'

Government spokesman Phay Siphan denied any suggestion that Kem Sokha was being held as a political prisoner, insisting he was guilty of treason.

He dismissed claims the government could be pressured into releasing Sokha by threats of sanctions or the potential removal of its preferential trade access for garment exports.

"EBA is completely different and cannot interfere with the court's decision," he said. "Let the court do their own process."

Monovithya says that she believes her father would not turn his back on politics or go into exile if released, like Sam Rainsy and most senior opposition figures.

Until then, she says, she has no hope of him being released on humanitarian grounds.

Kem Monovithya says her father will not turn his back on politics

"I don't think [Hun Sen] would release him just because he's in power and the election is done, because obviously this is not a decent person."

She believes the only chance of her father being released is if his detention becomes a genuine burden to Cambodia's long-serving strongman: "If there's no cost of keeping him he will continue to keep him."

George Wright is a freelance reporter based in Phnom Penh

- Published31 August 2018

- Published31 October 2017

- Published8 February 2018

- Published6 October 2017

- Published2 August 2016