Chinese gambling boom looms over Cambodia's Kampot

- Published

Kampot is one of Cambodia's cultural jewels, but as George Styllis writes, a flood of Chinese gambling money is making residents of this small sleepy town nervous.

During colonial rule - from 1863 to 1953 - the French would retreat to the lush highlands of Bokor mountain above Kampot to escape the stifling heat.

There they established an enclave, with a church, a post office and a magnificent hotel.

In the tumult of civil war and genocide, the hotel fell to ruin, leaving only black cavernous windows and a gruesome grey exterior.

It stood as a haunting monument to history - until this year, when it was reopened as a luxury hotel and casino under the banner, Le Bokor Palace.

There are now two casinos on Bokor with more expected to open once an 18,000-hectare resort, in the early stages of construction, is built.

This all reflects Cambodia's lurch towards gambling tourism. Casinos are tapping into demand among Chinese players for face-to-face and online play, both of which are banned at home.

The ease with which casino licences can be obtained, along with loose regulation, has triggered a gaming gold rush that is shaping entire cities around gambling.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Sihanoukville, a city two hours away from Kampot, which locals fear is a template for their town.

Sihanoukville has become the heart of Chinese investment in Cambodia, driven by growing manufacturing, tourist and gambling industries, and for its strategic position along Beijing's planned Belt and Road trade route.

Once a fishing village and backpacker haunt, its streets are now packed with Chinese supermarkets, flashy condos and casinos. Rapid development has seen streets torn up and recently caused the city's main market to flood for the first time.

Som Annie and her French boyfriend Damien Pradayrol, both 34, recently left Sihanoukville for Kampot.

The couple, who manage a hotel, couldn't keep up with the city's runaway growth which has seen property prices rocket amid insatiable demand for housing from Chinese expats, driving up costs.

They shared a small room for $75 a month for several years before the rent was abruptly increased. They had to move four times in one year, paying $250 a month for their last apartment, before leaving for good.

They say they know others who have moved from Sihanoukville to Kampot under similar circumstances.

"Before I liked Sihanoukville, but now I don't like it anymore," said Annie.

"My mother and father rent a home there too. Once the contract finishes, they will be kicked out and the home will be rented out to Chinese," she said. Her parents will move back to the countryside.

Alex Gonzalez-Davidson, co-founder of Mother Nature, a local environmental NGO, said Chinese-backed investments are perceived as cut-throat, with little regard for locals or the environment.

"Many of these Chinese investments come hand in hand with large influxes of Chinese nationals into the areas where they happen, which in many instances tends to push away the local population, or worsen their standard of living."

But Cambodians antipathy towards Chinese investment goes beyond personal grievances.

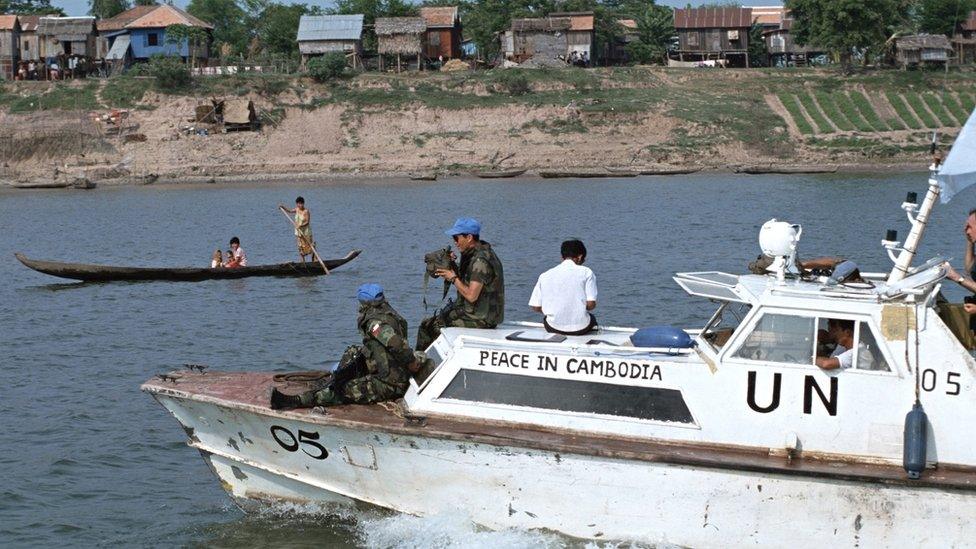

Prime Minister Hun Sen has forged a close alliance with Beijing while exerting greater authoritarianism and open hostility towards Western governments.

In July, he extended his more than 30 years in power after winning an election widely considered illegitimate following the dissolution by a court of the main opposition party and a crackdown on critical media.

Sihanoukville has become a symbol of China's modern imperial ambitions and its political foray into Cambodia. It speaks to a deeper fear that the country is being parcelled up and sold off, one province at a time.

"Anything Cambodia needs now we just get it from China, and so they just take what they want from us," said a tuk tuk driver in Phnom Penh.

China, however, does play an important role in powering the economy, investing in the things Cambodia desperately needs but can scarcely afford, such as new high-speed trains and airports.

Equally, entire industries in everything from agriculture to retail have gained vigour from blossoming Chinese trade, while individuals have landed sudden windfalls in real estate deals and other ventures.

But this economic advancement is a trade-off, said Anthony Galliano, CEO of financial services company Cambodian Investment Management.

"While China's investment capital hastens Cambodia's infrastructure and economic development for the benefit of the advancement of the country, it comes with some self-serving interests for China," he said.

These include the exploitation of low-cost labour and creating jobs for mainland workers abroad rather than employing locals, he said.

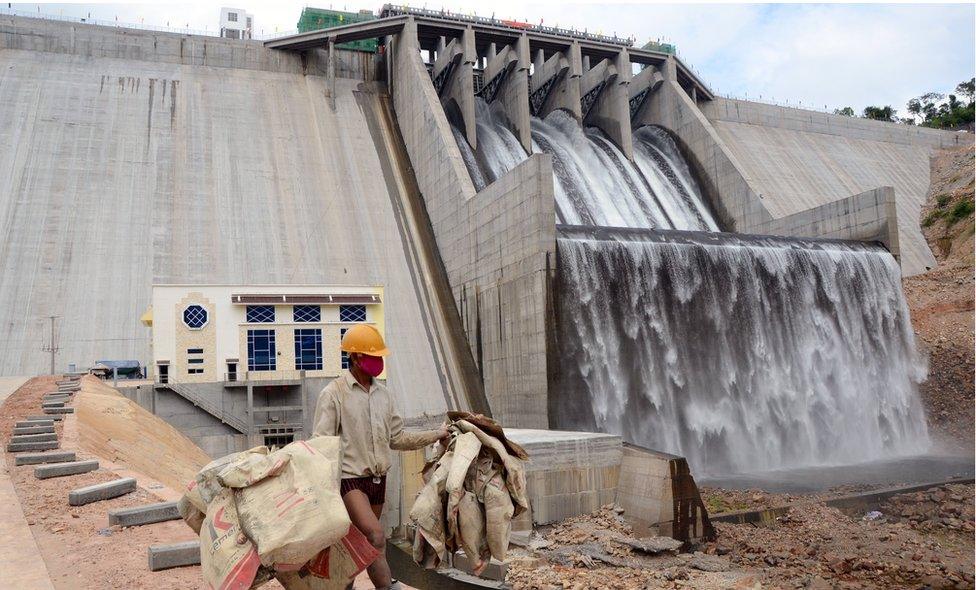

The Kamchay hydropower dam in Kampot province was built with Chinese money

A new 1,000-hectare special economic zone, with a deep-sea port and a coal power plant, both Chinese-backed, have been criticised for their impact on their environment.

Observing the transition convulsing Sihanoukville, many in Kampot view with cynicism industrial projects on their doorstep.

Ros Phirun, deputy director of the finance ministry, told the BBC there were no plans to allow casinos in Kampot outside of Bokor so as to preserve the town's "eco-tourism".

Yet cruises due to launch when the new port opens next year will ply the southern coast and stop at Sihanoukville, where they are expected to bring Chinese tourists and gamblers to Kampot.

While this could spell problems for housing tenants such as Damien and Annie, who are all too familiar with the whims of greedy landlords, others could make a fortune.

Chem Makara, a 26-year-old worker on a pepper plantation, said his small house had doubled in value, and that he was being made offers almost weekly by buyers visiting from Phnom Penh.

Yet as good as this sounds, for Makara preserving Kampot's idyllic beauty and history trumps making a quick buck.

"Kampot is a special place. We live here because we want to be closer to nature."

Referring to the new hotel on Bokor, no matter how fancy it may be, he said: "People prefer to see the old one. I hear all foreigners ask where it has gone. It was special. It had history."

George Styllis is a freelance writer based in South East Asia

- Published28 July 2018

- Published27 July 2018

- Published21 March 2018