How to protect reporters on Afghanistan's deadly front line

- Published

Tolo News journalist Samim Faramarz was reporting on a blast in Kabul when a second one killed him and his cameraman

More journalists have been killed in Afghanistan this year than in any other country.

And although the race to be the first at the scene remains competitive, the pressure is on media organisations to do more to ensure their reporters stay safe, reports the BBC's Najiba Feroz.

On 5 September, Tolo News journalist Samim Faramarz was reporting live on a suicide attack in the capital, Kabul. A few minutes later, a second attack at the scene killed him and his cameraman.

A car bomber had targeted emergency services responding to the first incident. In total, 26 people died and 70 were injured, including five more journalists.

Twenty-six-year-old Aman Farhang, who was covering the news for 1TV, was among them.

"I was close to the scene of the first explosion and was trying to speak to witnesses," he says. "Suddenly I heard a loud noise and I collapsed. I tried to stand up but couldn't and saw lots of people struggling to move. Next, I found myself at the hospital."

This was the second attack in four months using the same tactic - a follow-up blast that targets first responders, journalists among them.

On 30 April in Kabul, some 26 people, including nine journalists, were killed in twin blasts. One of those who died was renowned photographer, Shah Marai.

It was the deadliest single attack involving journalists in Afghanistan since 2001. The first explosion was carried out by an attacker on a motorbike; the second followed about 15 minutes later.

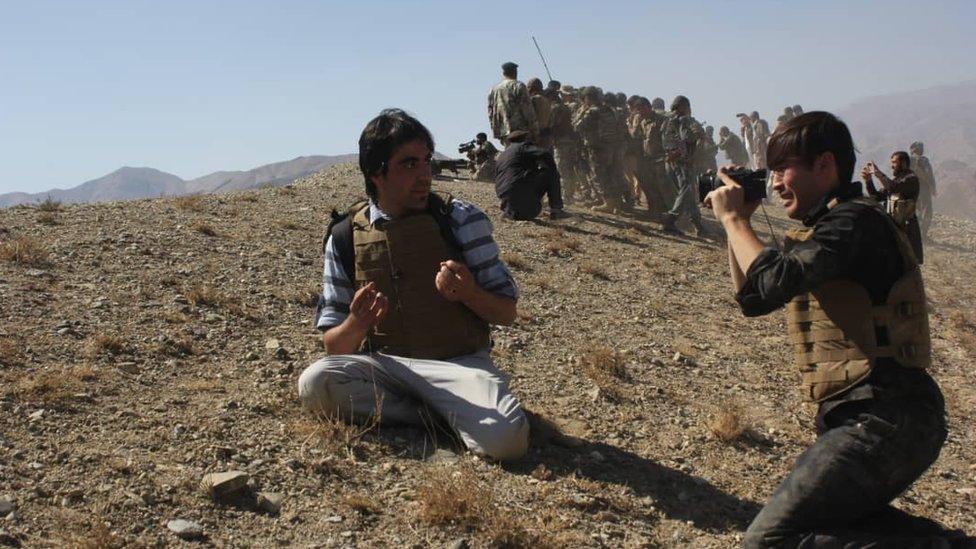

The 30 April attack used the tactic of a follow-up bombing

Despite the fact that the twin-bombings tactic has grown, Afghan media outlets still follow the routine practice of despatching journalists within minutes and expecting them to broadcast live from the scene.

So are news editors learning anything?

After losing its two journalists on 5 September, Tolo News, Afghanistan's first and biggest 24-hours news channel, issued new guidelines on how to cover security incidents.

Lotfullah Najafizada, head of Tolo News, told the BBC: "One thing we rethought is the distance that we should keep. In future, we might keep a longer distance when we cover incidents like a suicide attack, demonstration and natural disaster. It's also important that our journalists should have all the protection gear that is required, and for them to stay in touch with our security personnel."

Mr Najafizada also spoke about boosting security risk assessments and providing intense hostile environment training courses for journalists.

Costly competition

But I've spoken to a number of reporters and cameramen working with different media platforms in Afghanistan, and not every media outlet has safety training for their journalists or takes protective measures sufficiently seriously.

Aman Farhang, who was injured on 5 September, has been working with 1TV for only the past five months. He told me that he hadn't had any training during this period of time but had been sent to cover security incidents.

Tolo News staff work on, with a memorial to lost colleagues in the background

Emad Roustaei has been working with the same channel since 2014 and only once underwent training provided by the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee.

He told me that a number of times he had been sent to the scenes of bombings when not safely equipped.

"On 28 January, I was on my way to cover another story when I received a call from my news editor who told me an explosion had just happened in the city and to go to the scene now. I was told that I was the closest person to the area. I didn't wear a flak jacket and helmet and I went," Roustaei says.

The suicide bombing killed at least 95 people and injured 158 others in the centre of Kabul.

1TV head of news and current affairs, Abdullah Khenjani, admits there have been some cases where it has failed to take precautionary and protective measures before sending journalists to cover security incidents.

When asked about safety training, Mr Khenjani says 1TV does not have any budget for such programmes, but that it will make sure to assess the security risk before deploying journalists on the ground.

Emad Roustaei says there's pressure to be first on the scene

More journalists have been killed in Afghanistan this year than in any other country, according to the Reporters Without Borders, external.

The competition among many media organisations in Afghanistan has been very costly. "We are under pressure to be the first at the bomb scene and film or broadcast live the best shots," says Emad Roustaei.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, external' Asia programme co-ordinator, Steven Butler, told the BBC that precautionary measures should be taken by journalists, their employers and security forces in Afghanistan.

"All employers of journalists need to make sure that their journalists have the required training and equipment so they can do their job safely," he says.

A vibrant and young media is one of the great successes of post-2001 Afghanistan. But the media groups face extreme challenges and have always been under threat.

Reporters Without Borders says 60 journalists and media workers have been killed in Afghanistan in the past 17 years.

Aman Farhang says he has learned his lesson. "I will be extra cautious about my safety in future and won't go too close to a bomb scene, even if I lose my job."

- Published30 April 2018

- Published15 August 2018