Afghanistan election: What's at stake in the parliament vote?

- Published

Afghan "war on terror" generation votes

Afghans are once again set to defy threats, insecurity and fears over electoral fraud as they prepare to vote in parliamentary elections on 20 October.

The poll is long overdue. Bitter wrangling over electoral reform since the stalemate of the 2014 presidential poll has delayed it by three-and-a-half years.

So what's at stake for Afghans and their fledgling democracy, four years since most Nato troops left the country?

Why do the elections matter?

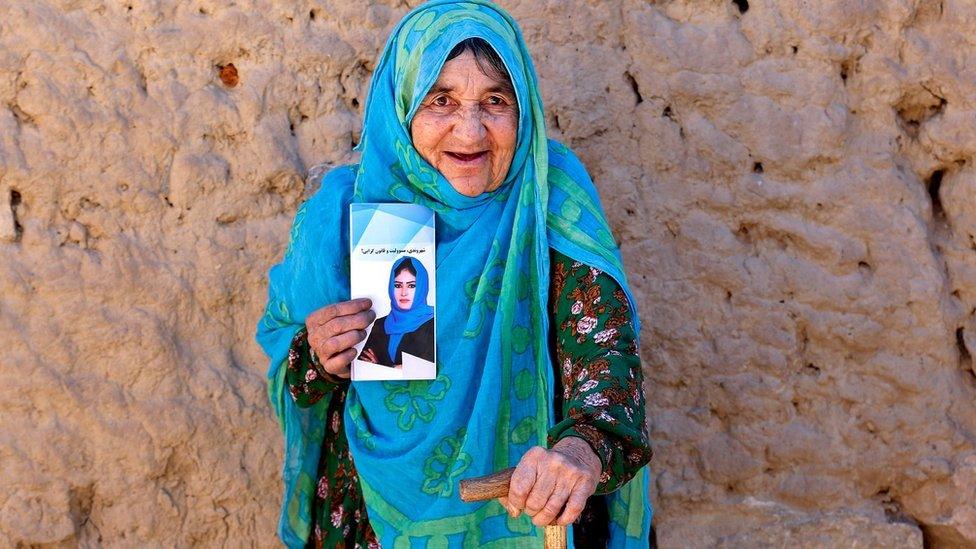

A woman in a camp for internally displaced people in Kabul holds an election pamphlet

Most Afghans are desperate for a better life, jobs, education and an end to the war with the Taliban.

For the country's foreign partners, seeing a flourishing democracy would be the return they're seeking after many years of investment, billions of dollars spent and thousands of lives lost in more than a decade of fighting.

This will be the third parliamentary election since the Taliban were removed in 2001.

They should have been held when the current assembly's five-year term ended in 2015. But the standoff after the disputed 2014 presidential election changed all that, bringing the country to the brink of civil war.

It needed the intervention by the Unites States to pave the way for the current government of national unity (with Ashraf Ghani as president and his main rival Abdullah Abdullah as chief executive officer, a prime ministerial post in all but name).

Both parties agreed a comprehensive review of the electoral system. Saturday's poll will be a test of the reforms undertaken and the ability of the country's much-criticised election commission to organise free and fair elections.

The poll is also seen as a test ahead of the all-important presidential elections due in April 2019.

How can you hold a vote amid so much violence?

The election will also test the readiness of the Afghan army and police who have been struggling to combat a rise in attacks by the Taliban this year.

It's also the first poll since Nato's combat mission ended in December 2014, placing security responsibility for the election primarily with Afghan forces.

Nato's Resolute Support Mission has promised to provide backup, as and when requested.

But with the Taliban openly active in as much as 70% of Afghanistan according to a BBC study published early this year, the security challenges are not being taken lightly.

The Taliban have urged people to boycott what they call "fake" elections. And Islamic State militants in Afghanistan have followed suit.

Since the poll was announced there have been several attacks on voter registration centres, the deadliest killing almost 60 people in Kabul in April and claimed by the Islamic State group.

At least 10 candidates were killed in attacks around the country in the run-up to the vote.

But Afghan officials have vowed to fully secure the elections and open most polling centres across the country.

In previous polls as many as 10% of polling centres remained closed because of security concerns. This time about a third of the more than 7,000 centres will be shut.

So what about fraud?

Afghanistan elections: Running an election in a war-torn country

Security isn't the only issue threatening the vote. Past elections have been marred by corruption and fraud, with cases of ballot box stuffing, multiple voting and voter intimidation all documented.

Ahead of the current elections, the problem of over-registration of voters in a handful of provinces has raised concerns with some observers.

In five provinces, the number of registered voters was higher than that of the estimated eligible voting population, according to figures published on the election commission website.

An Independent Election Commission worker tests a biometric device at a warehouse in Kabul

The anomaly appears to be in part due to the lack of a system that connects individuals to a physical address and a specific constituency, and the lack of a central database which collates everyone who has been registered.

Following protests by several political groups, the election commission agreed to demands to use biometric verification machines at all polling booths.

More than 20,000 of these hand-held devices are being distributed so voters' fingerprints and pictures can be taken, in an attempt to make sure no one votes twice.

There are fears the process may disenfranchise some voters, because the election commission says it will only accept votes validated through the biometric system, so technical faults or missing devices my cause problems.

Who's standing?

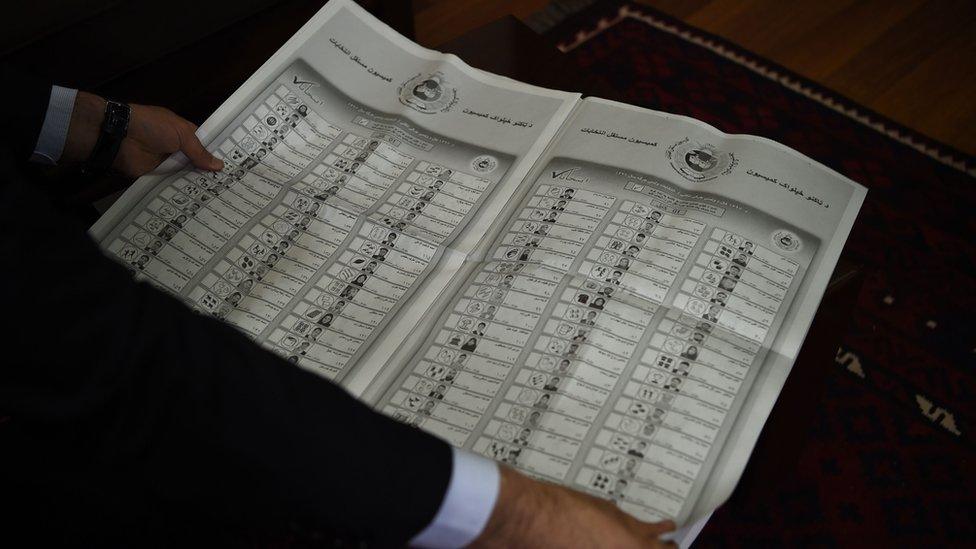

A newspaper-sized ballot paper for Kabul, featuring more than 800 candidates over 15 pages

More than 2,500 candidates are standing, meaning that on average there are at least 10 people contesting every seat in parliament.

There is no party political system so candidates run as de-facto independents, although many are linked to political groups and factions, often based on ethnic loyalties.

All this leads to a fractured political system, most visibly in Kabul where more than 800 candidates vie for 33 seats, leading to a very long ballot paper.

Among candidates who have close ties with former warlords, powerbrokers or current parliament members, using patronage and family ties is common.

Some of the most prominent include the sons of second deputy CEO Mohammad Mohaqiq, Hizb-e Islami leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Vice President General Dostum.

But for those who are hoping for change from the status quo of established politicians, there is a silver lining in the many campaign posters of young, educated candidates visible in Kabul and beyond, among them many former journalists, entrepreneurs and government employees.

What about women?

Seemi Barakzai, seen her next to a poster of herself, is a candidate in the western city of Herat

Securing women's rights has always been a declared priority for Afghanistan's foreign backers.

That's reflected in the Afghan constitution which guarantees 68 seats - or 27% of the total - for women MPs, regardless of their vote share.

And while this quota system has ensured that Afghan women participate in the legislative process, inequality and especially domestic violence remain huge problems. And parliament has remained dominated by conservatives.

In 2016 President Ashraf Ghani introduced the first woman candidate ever to sit on the bench of the Afghan Supreme Court, but parliament did not back her.

During 2018 the president sought parliament's approval for 11 ministers. The only one who failed to win the backing of MPs was a woman.

The house also failed to pass legislation to defend women's basic rights, rejecting the law for the Elimination of Violence against Women. The bill was then passed by former President Karzai by decree in July 2009.

Whether the 400 or so female candidates in the forthcoming election will secure a stronger voice for women remains to be seen. One indication might be if women secure more seats than allocated by the quota system.

In the 2010 election, women candidates beat the quota by just a single seat.

What happens after the vote?

While in most countries initial results or exit polls come within 24 hours, in Afghanistan the process takes rather longer.

That's in part due to logistical challenges like transporting the ballot boxes to Kabul from remote and insecure areas, and because of a multi-stage counting and verification process.

In some parts of the mountainous north, villagers used donkeys to transport election materials for the 2014 vote

There will be three rounds of announcements: initial, preliminary and final results.

After voting ends, polling stations conduct a first vote count in the presence of observers. The initial results sheet is sent to Kabul in a secure bag and a copy is posted outside the polling centre.

Further copies go to the candidate with the most votes, to the provincial complaints commission and another is placed inside the ballot box before it is sealed and transported back to the capital.

Once the boxes have arrived at the Election Commission's main office, the votes are counted again.

Preliminary results are expected 20 days after the election, on 10 November. That's followed by a lengthy period in which complaints can be made and addressed.

Final results are due by 20 December.

- Published31 January 2018

- Published2 October 2018