New Zealand whales: Why are so many getting stranded?

- Published

Almost 150 whales died in a mass stranding on NZ's Stewart Island

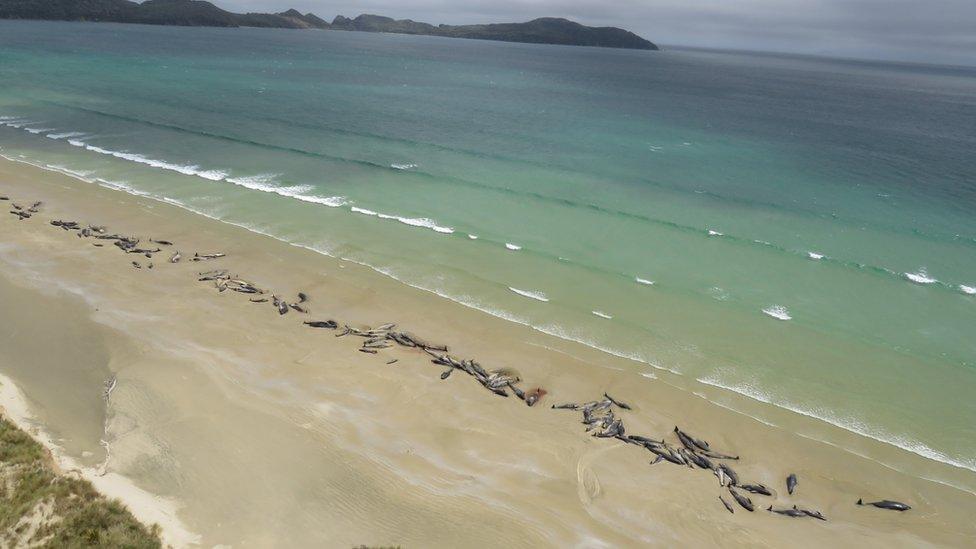

The pictures are striking: dozens of whales lie stranded on an idyllic beach in a remote part of New Zealand.

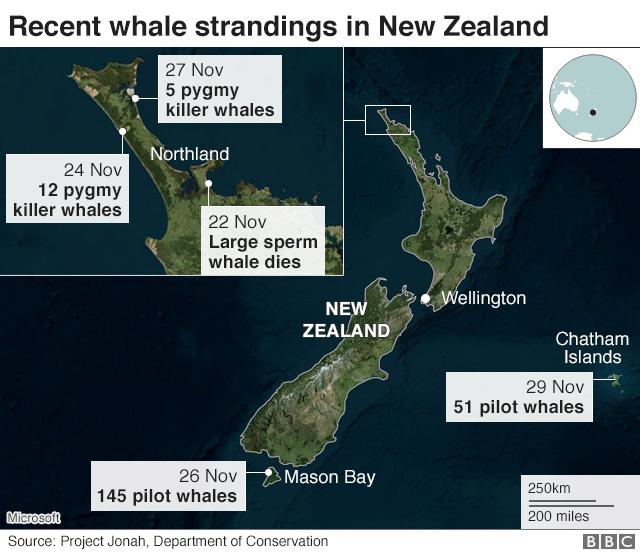

The group were found by a walker on Stewart Island earlier this week. And just a few days later, a further 51 pilot whales died after becoming stranded on a beach on the Chatham Islands.

While whale strandings are not uncommon, they usually involve just a single animal rather than a whole group. The recent flurry of mass strandings has brought a renewed focus on the mysterious, and rare, phenomenon.

So why does it happen? While the exact reasons remain unclear, experts say many different factors could play a part.

Sickness and injury

"Quite often animals that turn up on a beach are getting exhausted, they're malnourished, or they haven't eaten because they're ill," says Dr Simon Ingram, a Professor of Marine Conservation at the University of Plymouth.

"They can be in the final stages of being ill or die at sea and end up getting washed up on a beach," he adds.

But Dr Ingram says that sickness or injury mainly plays a part when a single animal is found stranded.

"The trouble is that in a huge number of animals it's quite likely that some of them are going to be ill anyway," he explains.

It's also true that there have been cases where groups of healthy whales have ended up getting stranded. So what could be behind these cases?

Navigational mistakes

Some experts say that certain aspects of the coastline or sea bed can disorientate whales, especially if they roam outside of their usual habitat.

"Some places like the tip of New Zealand are hotspots for stranding," says Dr Ingram.

"Sometimes this is due to geographic features of the coastline. If there's a feature like a peninsular or headland then animals that should be in deeper [waters] may suddenly find themselves in a confusing, shallow bay."

Dead pilot whales on a beach in the Chatham Islands, New Zealand

Shallow water can pose a risk to pilot whales in particular because of the way in which they navigate and communicate.

"These animals forage and feed largely by echolocation," says Dr Andrew Brownlow, a veterinary pathologist who has undertaken post-mortems on stranded pilot whales in Scotland. "So they use sound to navigate and communicate and find their prey."

"Using echolocation in areas with very shallow, silty mud is like trying to walk through a forest on a foggy day," he explains, "It's very hard to get your bearings and see clearly."

This combination of shallow waters and confused, muddled, echolocation is a serious danger and may lead to mass strandings.

"They end up coming into shallow areas and get stranded by the receding tide, so the natural lay-of-the-land is a real risk factor for these animals," Dr Brownlow says.

Many of the whales had severe injuries from being caught in the shallow water

Following the leader

But if a single whale gets injured or lost, why do they end up beached in such large numbers? Experts say the answer lies in their herd-like behaviour.

"It's a problem you get with these very social animals that tend to, for reasons we have never been clear on, end up following either a sick leader onto the beach or end up getting lost as a group," Dr Brownlow says.

"This particular species seems to be very prone to that herd behaviour."

Pilot whales are incredibly social and may follow one another into hazards such as shallow water

It means that if one pilot whale encounters a problem then it can have an impact on the entire group.

Dr Brownlow points to one case in 2015 when around 30 whales became stranded on the Isle of Skye, off Scotland's west coast.

"We think that was because one of the females was having trouble giving birth and was in a lot of distress," he explains. "She came into shallow waters, and all the other members of the group followed her onto the beach."

Warming waters

Another possible cause of strandings, some experts suggest, is warmer water temperatures.

"We've had an unusual week, which we haven't got to the bottom of, and it's fair to say it's been an entirely unusual year," Dr Karen Stockin, a marine mammal scientist based at New Zealand's Massey University, told AFP news agency after the latest mass stranding.

"I suspect a lot of that has been driven by the warmer sea surface temperatures that we're seeing at the moment."

She explained: "That's likely affecting where the prey is moving and as a consequence we're seeing prey moving and [whale] species following."

New Zealand's summer begins on Saturday and Dr Stockin warned that there could be more beachings to come.

"We're just going into stranding season now, this is only the beginning of it and we're very mindful of the fact that this a very busy start," she said.

While Dr Stockin says that global warming may be playing apart in the rising sea temperatures, most experts say that it's important not to jump to conclusions about the role of humans in these cases.

"Pilot whales have probably been stranding in New Zealand since before people lived there," Dr Ingram says. "It's probably not anything to do with what humans have done."

"It's a very dynamic ecosystem that these animals are in, so I would be very cautious in making any connection between these examples and climate change."

- Published30 November 2018

- Published26 November 2018

- Published27 November 2018

- Published26 November 2018

- Published15 August 2018