Lost in Asia's deepest cave

- Published

Boybuloq cave is now recognised as the deepest in Asia

Almost 50 years ago, Mustafaqul Zokirov left his drought-hit mountain village in a remote corner of Uzbekistan in search of water.

He never returned.

But his disappearance led to a discovery that now draws explorers to a Central Asian country normally known for its vast deserts and ancient Silk Road cities.

What attracts them is Boybuloq - at 1,415 metres (4,640 feet) - Asia's deepest cave.

The Hisar mountains where Asia's deepest cave is located

Uzbekistan's mountains still have an air of mystery and are amongst the least explored anywhere.

That's certainly true for the Hisar range in the south of the country, where Boybuloq lies.

Just getting there is a task not for the faint-hearted. First comes a hair-raising seven-hour drive in an old Soviet-era UAZ off-road vehicle, up to the hamlet of Dehibolo - which translates as "the highest village".

As the mountains disappear in the clouds on one side, steep gorges promise certain death on the other should your driver make the smallest mistake.

The view from a Soviet-era UAZ four-wheel-drive vehicle

"I even ride in winter and at midnight," boasts our young chauffeur Erkin. "I know every stone and every bend. So relax and enjoy the view."

Once we reach the last few villages, the road disappears altogether and the car has to make do with a river bed amidst steep barren cliffs, springs and narrow streams.

At an altitude of over 3,000m, Dehibolo marks the end of the journey, a small green oasis at what feels like the end of the world.

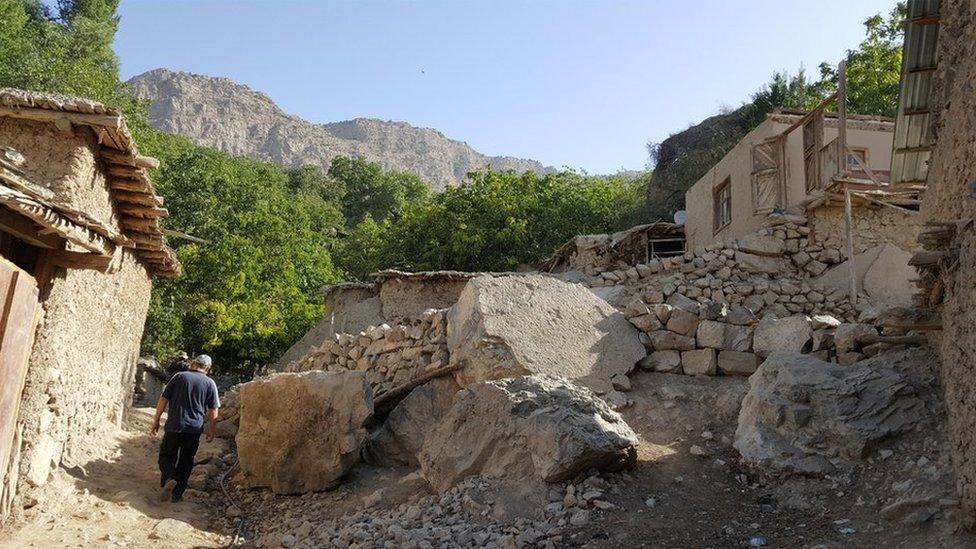

Patches of fertile ground have been cleared from the rocky ground in Dehibolo village

The dwellings of Dehibolo have been built into and around the rocks and boulders

During the snowy season from late January to mid-April, the village is completely cut off. People here have to produce almost everything themselves, except clothes, medicine and flour.

Villagers keep honey bees, rear sheep, grow fruit and vegetables and all summer they have to gather either firewood or coal in the surrounding mountains to keep them going through winter.

"Life here is tough," says Norkhol-momo, 70. "All my children have moved away, just my youngest is still here."

Everything here is built into the rocks. Norkhol-momo's courtyard is also the roof of her neighbour's place.

Like her fellow villagers,. Norkhol-momo lives a life of self-sufficiency

Growing food is challenging in these narrow, rocky valleys. People spend years clearing rocks away to make room for small gardens where they can grow fruit or vegetables.

For water they rely on rain and a few natural springs, and any dry spell can pose danger for the community.

In 1971, a bad drought hit the village and all the springs dried out.

So Mustafaqul Zokirov, a local carpenter and father of eight, decided to do something about it.

He knew that water came from a cave in the high mountain, a four-hour walk away. Taking his son and several donkeys and water canisters, he made the trek to the Boybuloq spring.

Little did he realise that this was to be his last trip - nor that it would later lead to one of the biggest geographical discoveries in the world.

Local springs are the essence of life in Dehibolo

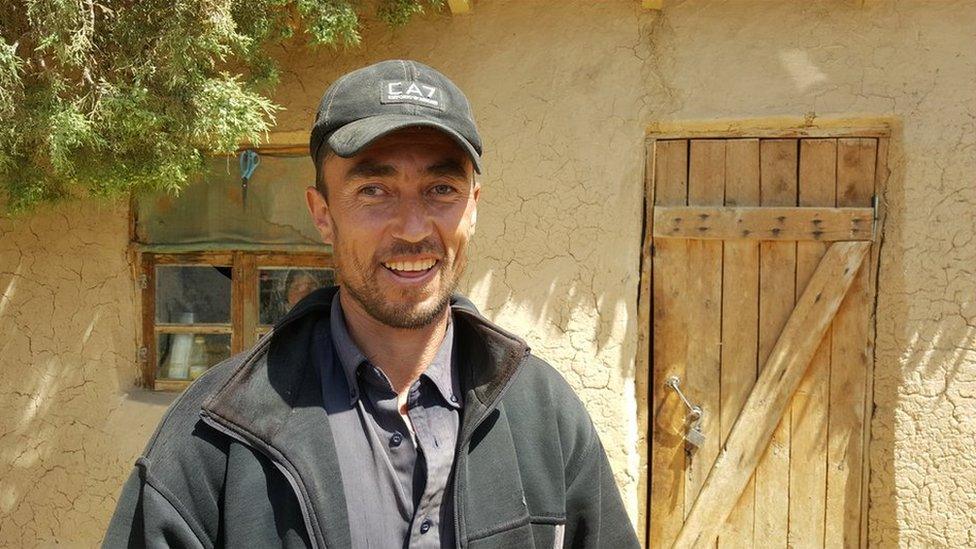

Shahobiddin is proud of his grandfather's legacy

His grandson Shahobiddin recounts a story passed on through the family. "He left the donkeys and my then teenage uncle by the entrance and entered the cave, but never came back.

"His son waited all night and the next morning alerted the village."

Young men from the village entered the cave but no trace was found for the next 14 years.

Then in 1985, a group of Russian explorers came to the village. After hearing the story, they offered to look for Mustafaqul.

Two years later they found his remains, in one of the deepest corners of Boybuloq, the lamp still lying next to his bones.

The search had led them to what is now recognised as the deepest - and one of the least explored caves - in Asia.

The trek to Boybuloq leads along narrow paths and steep rock faces

We too made our way to the cave entrance, a small hole set in a rock face.

Despite an outside temperature of 30C, a cold wind blew from the mouth of the cave.

Just beneath the opening we saw the small spring Mustafaqul had come to find.

Now - nearly 50 years on - a new drive to open Uzbekistan to visitors is bringing paying clientele to this remote spot.

This year a joint Russian-French-Swiss expedition was on site.

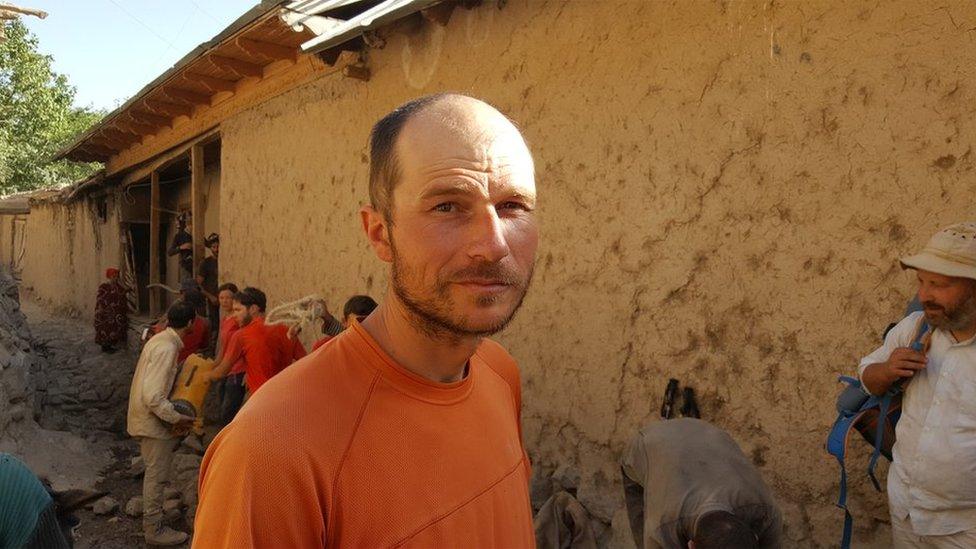

Vadim Loginov hopes to find a connection between the Boybuloq and Vishnevsky caves

"Our main task was to find a possible tunnel that connects the two deepest caves in the Chulbayir mountains - the Boybuloq and Vishnevsky caves," expedition head Vadim Loginov explains.

"They are actually positioned in such a way that we assume these two are in fact a single long cave."

If it can be proven, the two systems would become one of the deepest in the whole world.

But it's not an easy task. Vadim Loginov says they have found new rivers and lakes inside the cave. "An inexperienced person won't survive here."

While we were there, a small group of Swiss and French explorers entered the complex.

The international caving team explored underground and hope to return next year

"You cannot find such a deep cave at a height of 3,000 metres anywhere in the world," says Arnauld Mallard from Switzerland.

His team have been into the Vishnevsky cave, which is around 735m deep, and now plan to return in 2019 to enter Boybuloq and look for the elusive connection.

For the villagers of Dehibolo, the explorers offer a connection of a different kind, an opening up to the rest of the world.

Bakthiyor Imamov contributed towards this article