The pioneering medics who drove across the world to help Nepal

- Published

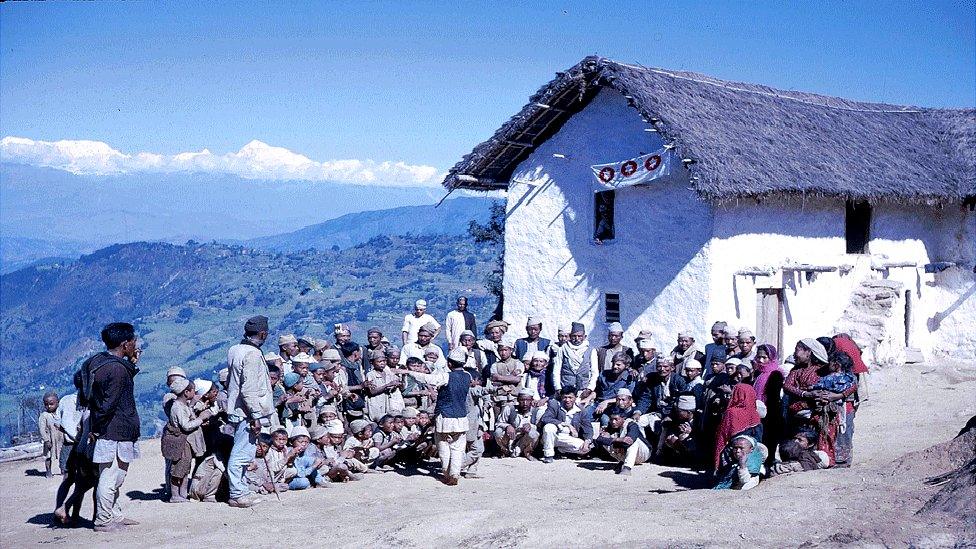

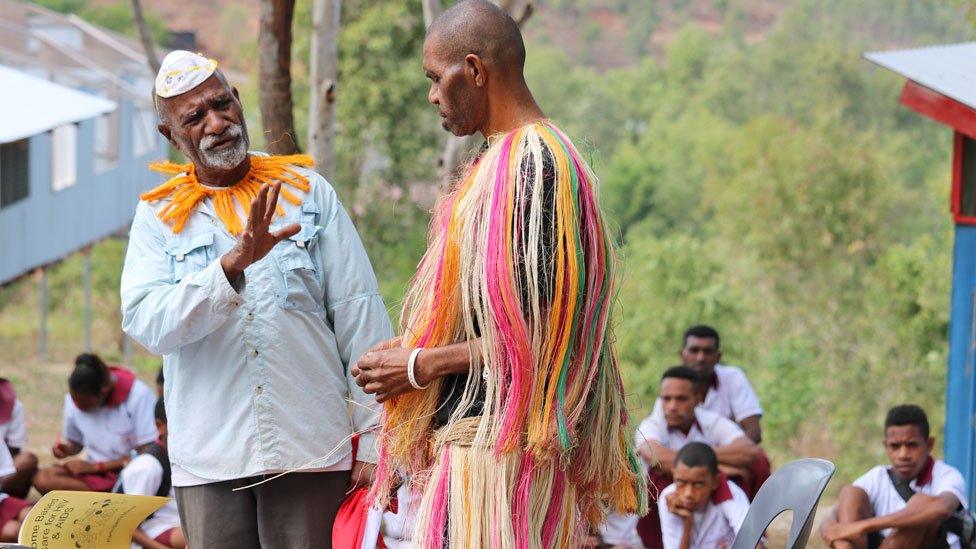

Villagers in the eastern district of Dhankuta

Fifty years ago a group of young doctors and nurses drove from the UK to Nepal, a country desperately short of medics. The health services they helped set up have saved millions of lives since, reports the BBC's Bhagirath Yogi.

In three donated Land Rovers laden with equipment, the 11-strong team left in early April 1968.

Through Europe they drove to Istanbul and then crossed Iran and Afghanistan, reaching Pakistan via the Khyber Pass, before continuing to Delhi. Such a journey would be unthinkable these days for security reasons.

But they did it in about seven weeks and by the end of May they had reached Nepal's capital, Kathmandu.

The overland route the group chose was cheaper than going by sea and road, which would have been no quicker.

In Nepal, they set up an anti-tuberculosis programme, trained health workers and immunised children. It wasn't just local lives that were changed - several of the group ended up marrying each other in the then Himalayan kingdom.

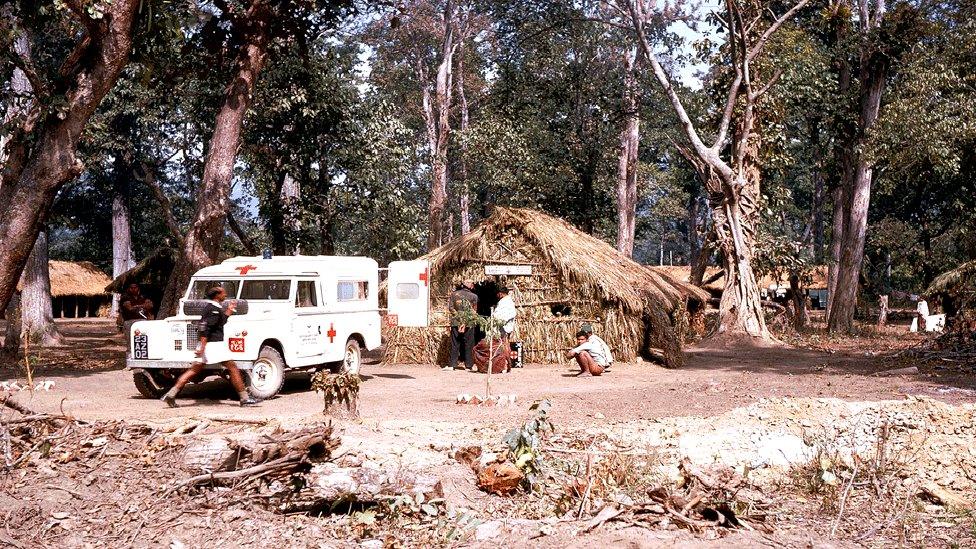

Tuberculosis was a major disease in Nepal's hills

The idea for the trip had come two years earlier. John Cunningham, a doctor at St Thomas's Hospital in London, wanted a challenge and found that Nepal had just 200 doctors for 11 million people. A positive reply to a letter to the Nepalese government enthused him - and in 1967 he registered a charity called the Britain Nepal Medical Trust (BNMT).

"John was a consummate organiser and recruiter," recalls Dr Barney Rosedale, a member of the expedition.

By early 1968, those organising powers "had wrought a miracle, in fact several miracles. Mountains of donated equipment and medicines had been sorted and packed for shipping to Calcutta".

Among those on the team was nurse Pru Hunt, the daughter of John Hunt, who led the first expedition to the summit of Mount Everest in 1953. The youngest member was handyman Peter Hawksworth, 19.

"We had two other Land Rovers, a full team, and John had visited Kathmandu for preliminary discussions with the government. There was much debate about where we should go," says Dr Rosedale.

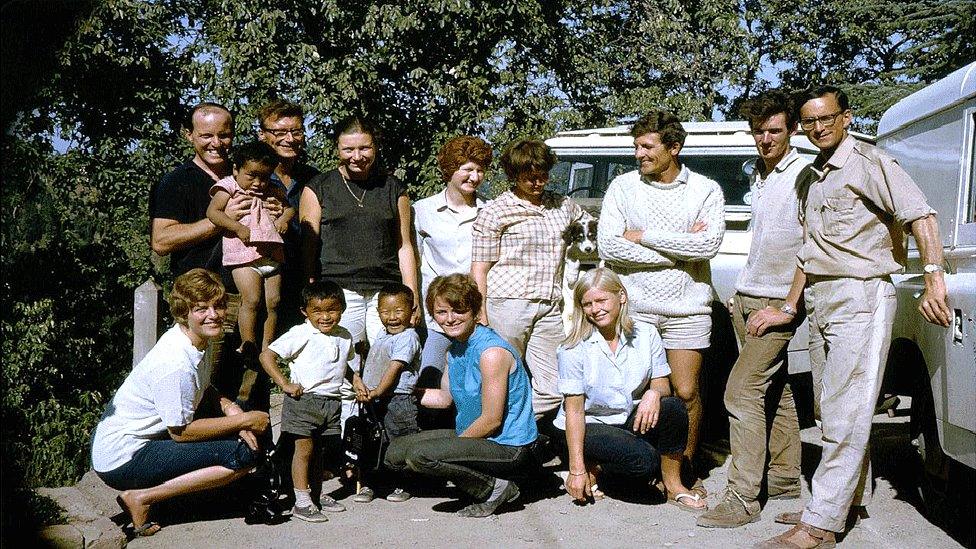

Some of the team en route to Nepal. Dr Cunningham is second left, Dr Rosedale far right

First, they went to Kathmandu.

A couple of hours from the capital, the entourage stopped at a river crossing and washed the vehicles and themselves. Suits, ties and dresses were donned, and at 4pm on 28 May 1968, looking bizarrely smart after seven weeks on the road, the team drove into the British embassy in an early monsoon rainstorm.

"We spent a couple of months in the capital, finding our way around, making many friends and contacts," Dr Rosedale says. "We learned Nepali from a Peace Corps tutor."

It was confirmed they would be working in the east, in Biratnagar. In those days the town was much smaller than now, surrounded by expanses of flat rice and jute fields with slow shallow rivers and many bullock carts.

The team settled in and soon established a new children's ward at Biratnagar Zonal Hospital under Dr Bharat Raj Baidya. A programme of nurse training followed, along with more surgery and, later, a large, new outpatients' building, with a modern pathology lab upstairs.

A father and his baby son with advanced TB in Dhankuta in about 1969

In nearby hills, the town of Dhankuta, with its one doctor and small hospital, was next to receive help.

With a host of porters carrying their surgical equipment, some of the team were met on the way by the husband of a woman seriously ill in long obstructed labour.

That evening they performed a Caesarean section on her in the hospital. Mother and baby boy survived and thrived. And the chief district officer, whose wife it was, was impressed.

"A good omen for our career in the hills," Dr Rosedale says.

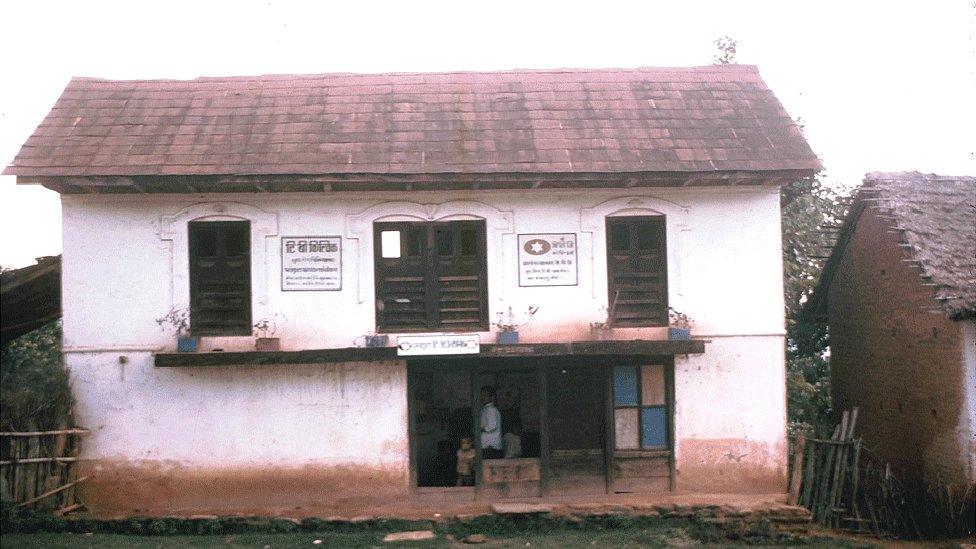

"Our first TB clinic was in an old house nearby, near the hospital... with a consulting/treatment room downstairs and laboratory for sputum staining upstairs, the waiting area on the steps outside. TB drugs were supplied by Unicef."

The first TB clinic at Dhankuta, established in 1970

It was soon clear that TB was a major disease in Nepal's hills, far commoner and more deadly than leprosy, which the team also diagnosed and treated.

It was also clear that although treatment was vital, prevention on a huge scale would be better value, so the team organised and started a BCG programme, both in districts where the doctors and nurses could visit by Land Rover or motor bike, and in the hills entirely on foot.

First, a motivator would be sent a few weeks ahead to explain the programme to the elders of the villages and to arrange times and places.

Then the doctors would arrive, vaccinate, give some health education and move on to the next village, sleeping in village houses.

The young doctors and nurses were among a handful of medics in the country at the time

In the first four seasons of the programme they vaccinated about half a million children in Koshi zone, and much of Mechi zone too, and also put forward a plan for a national vaccination programme.

"In those early days we had the support of Oxfam and individual donors who loved Nepal, but we were always short of money," Dr Rosedale says.

Even before TB clinics were established in many further hill towns, the lack of reliable, in-date and affordable medicines became a clear problem.

Dr Rosedale at a BCG vaccination programme in Dhankuta district, circa 1970

The Hill Drug Scheme devised by Dr Rosedale - to ensure a supply of carefully selected vital drugs at a controlled cost to strategic points - was gradually unfolded to 20 distribution centres, with its own accounting and portering systems. The scheme evolved and expanded to meet a far wider need over the decades.

According to Dr Rosedale, much of the ethos and tradition of the trust was formed in those early days, involving a small team that was egalitarian, secular and non-missionary.

Key principles were working alongside the government services, managing on a small budget and using local resources.

This, he says, made the team flexible enough to tackle a cholera outbreak in 1971 or assist at an eye camp in the hills; and establish a service which has kept evolving to this day.

Dr Rosedale (second from right) and some of the original team were received at Nepal's London embassy

In March 2018 Gillian Kellie and Rosemary Boere, two of the nurses back in 1968, visited the hospital at Biratnagar along with Peter Hawksworth, the team's handyman.

So how have things changed over the last five decades?

Gillian says Koshi Zonal Hospital is almost "unrecognisable".

"The old compound was packed with buildings containing all the departments of a teaching hospital. The medical superintendent, Dr Roshan Pokharel, told us there were 344 beds including a 100-bed maternity wing and a 21-45 bedded children's ward.

"Three theatres with purpose-built scrub and sterilisation rooms had replaced the one small theatre where I worked," she told the BBC.

These days the hospital looks nothing like it did in 1968

The young British doctors and nurses were among just a handful of foreign medics assisting Nepal when they arrived in 1968.

The country is still very poor but these days it has more than 21,000 doctors for a population which has grown to 29 million. And TB is still a major health problem but treatment coverage is now 70%, according to the World Health Organization.

"Our expedition changed a good many lives, including our own, and best of all, we have come to share increasingly the mantle of this work with our Nepali brothers and sisters, to the benefit of a country we have all come to love," says Dr Rosedale.

- Published25 July 2018

- Published24 March 2017

- Published15 July 2024