How Sri Lanka's arrack coconut spirit went upmarket

- Published

Sri Lanka's arrack producers are trying to take the spirit upmarket

Distilled from the sap of the coconut flower, Sri Lankan arrack has been a local favourite for centuries. But now its makers are trying to take the spirit global, writes the BBC's Ayeshea Perera in Colombo.

It's served in some of London's most fashionable restaurants, like Dishoom and Hoppers.

And the late food and travel writer Anthony Bourdain described it as tasting like "a marriage of bourbon and rum, but with a stronger, burning kick and a mysterious bouquet".

Yet the makers of Sri Lankan arrack - best described as a dark coconut rum - believe it is still punching far below its weight when it comes to international recognition and appreciation.

For years, arrack was considered too "low class" to be taken seriously as a premium alcohol, even in Sri Lanka, whose elite in the capital Colombo preferred Scotch whisky, wine or rum.

Arrack is distilled from the sap or toddy of the coconut flower, which is still harvested by hand

Arrack's makers have also had to survive multiple Sri Lankan governments who have taken the view that while necessary for revenue, the local alcohol industry is a terrible influence on society, rather than a business that ought to be nurtured.

Distilleries are therefore subject to heavy taxes, and advertising spirits is prohibited by law.

Despite these impediments, attempts to raise the quality and profile of the drink at home and overseas appear to be paying off.

Premium versions of arrack have found lucrative markets both in Sri Lanka and other countries, where it is marketed as a smooth, artisan spirit that can be either drunk neat, or used in cocktails.

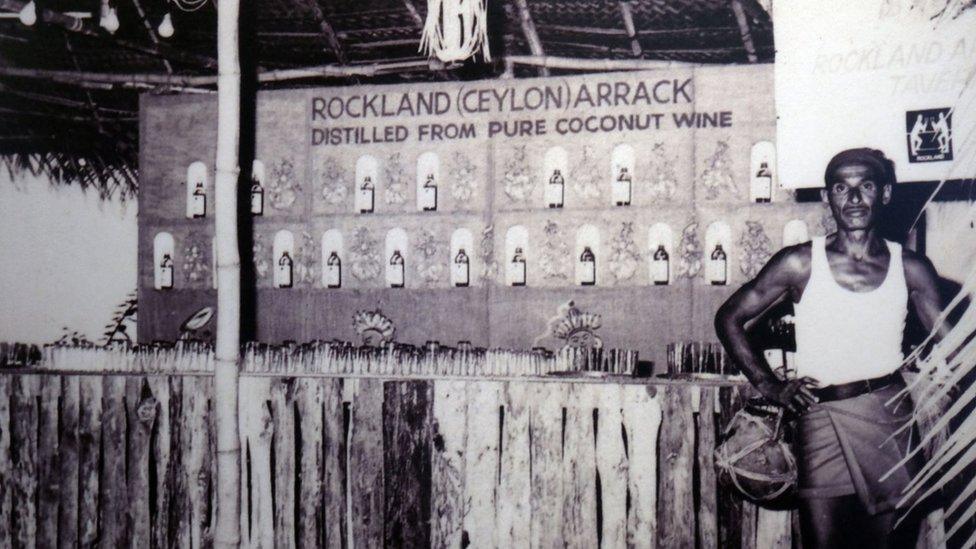

Amal de Silva Wijeyeratne, the managing director of the country's oldest arrack producer Rockland Distilleries, is at the forefront of these efforts.

He passionately points to the fact that quality arracks are made from just two ingredients - coconut flower sap (known locally as toddy) and water.

And for him, it's in his blood.

The sap ferments naturally after it has been harvested

His great grand uncle, JBM Perera, is credited with completely changing the way the drink was distilled and blended, when in 1924, he accepted a British government contract to produce arrack on a commercial scale.

His innovations, including the procurement of a custom-made still from a French company, helped transform arrack from a crude liquor into a smoother and more sophisticated drink.

Mr Wijeyeratne says he is trying to continue that legacy of innovation.

Part of this was his company's introduction of an upmarket, barrel-aged blend called Ceylon Arrack, which he says has been made to appeal to drinkers around the world.

And it is making some significant inroads in the global market.

First introduced in the UK back in 2002, which Mr Wijeyeratne calls the "toughest liquor market in the world", he says that Rockland now sells more Ceylon Arrack to British buyers than those in its home market.

The brand is now also sold in countries like Singapore, Germany and Japan. And there are plans to launch it in India this year.

Working as a "toddy tapper" collecting the coconut flower sap is not for those who are scared of heights

Singaporean bar Native uses Ceylon Arrack in one of its cocktails, and its owner and head bartender Vijay Mudaliar says it has been a bestseller ever since they introduced it.

"Arrack is a beautiful spirit. The taste profile is very fresh and clean. Aged arracks are definitely a viable choice for any dark spirit drinkers."

There is no way of really knowing how long Sri Lankans have been drinking arrack, but it is believed to be one of the oldest spirits in the world.

According to Mr Wijeyeratne, that's because "God has already taken care of the fermentation process".

What he means by this is that the toddy ferments of its own accord, because it contains both natural sugars and yeasts.

Rockland is Sri Lanka's oldest commercial producer of arrack

As soon as it is collected from the trees, it's a sweet, slightly tangy white liquid. But the fermentation process is rapid and its alcohol percentage increases in just hours to around 6%.

It is then distilled like whisky or brandy to an alcohol level of more than 60%, before water is added to bring that back down to 40%.

Global Trade

However, collecting the coconut sap is not for the faint hearted.

In a process that has remained unchanged for generations, men known as "toddy tappers" twice a day shimmy up the unnervingly tall coconut palms - a fully grown tree can reach 60m (200ft) - to collect toddy from the unopened flowers.

Sri Lanka's four major arrack producers - DCSL, IDL, Mendis and Rockland - employ hundreds of tappers on their vast coconut estates.

With each tapper given a group of trees to look after, they stay high above the ground for hours, using crude rope bridges to move between trunks.

Together the four firms produce about 60 million litres of arrack a year, in different grades and mixes.

Sri Lankan arrack has become increasingly popular both in Sri Lanka and overseas

The price and quality of arrack has a lot do with the percentage of actual toddy in it.

While the premium versions are made from 100% distilled sap, cheaper blends - which are somewhat erroneously called "Extra Special Arrack" - are usually also made from molasses, a form of treacle.

Some of the most basic versions of arrack can actually contain as little as 3% toddy.

Although lower grade arrack still accounts for almost 70% of sales in Sri Lanka, the premium versions are making Sri Lankans feel that they can take pride in the drink.

"Many Sri Lankan CEOs I meet tell me that they don't travel without a bottle of arrack as a gift for their high profile international clients," says Mr Wijeyeratne.

He adds that changing the perception of the drink continues to be a slow but rewarding process.

"It takes years and years. You have to be willing to go for the long haul."

"It's still going to be a long time before arrack gets the attention and recognition it deserves."