Viewpoint: Thai coronation heralds an unpredictable reign

- Published

After the 70-year reign of a revered and widely-loved king, Thailand's transition to the new era of his son, Maha Vajiralongkorn, was always going to be an uneasy one, an analyst reports from London.

No-one knew what to expect when King Vajiralongkorn took the throne in one of the world's most powerful monarchies at the end of 2016.

The new king's controversial lifestyle and mercurial personality, and his lack of interest in the development projects so proudly promoted by his father, gave him a more remote and forbidding public image.

Two-and-a-half years later, an elaborate coronation has formally consecrated King Vajiralongkorn's reign. What have these 30 months told us about the new king?

The severe restrictions on open discussion of the monarchy, and the deep-rooted fear of doing so in Thailand, make it difficult to penetrate the veil of secrecy that surrounds the royal institution. But this king has already made his mark, with actions that contrast sharply with those of his father.

As he did before he acceded to the throne, he spends much of his time in a large villa in southern Germany, where his 14-year-old son by his third marriage, Dipangkorn, is being educated. Those close to him say he prefers the less formal lifestyle he can lead there.

But he has started reshaping the monarchy, restructuring the palace bureaucracy and security apparatus to put them more firmly under his control, and dismissing staff who displease him with unusually blunt public statements, sometimes condemning them as lazy, or accusing them of "extremely evil acts".

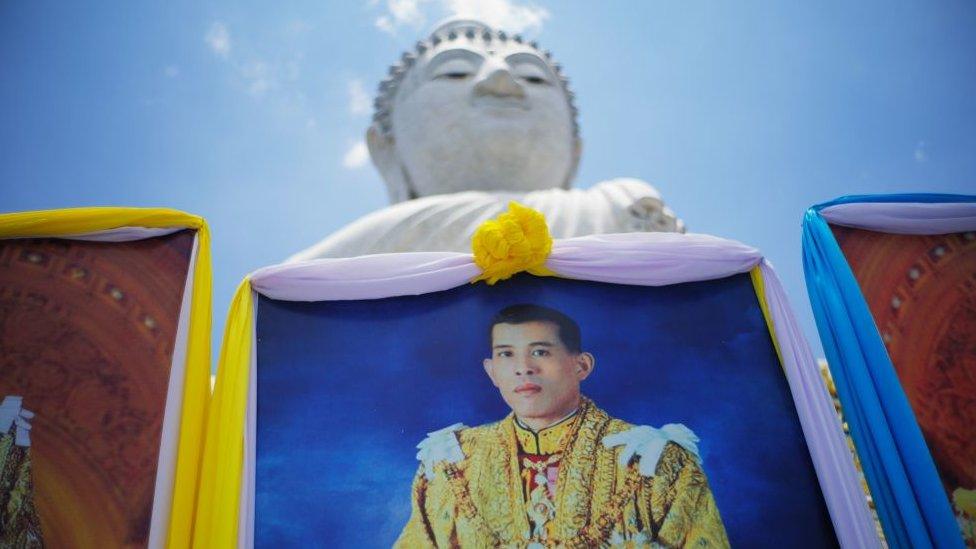

In Thailand there is a deep love and reverence for the monarchy

Some of these officials have been publicly humiliated and faced criminal charges. Jumpol Manmai, a former senior police officer and once one of the king's top advisers, was arrested and charged two years ago. There are persistent reports, impossible to confirm, of harsh punishment routines imposed on those who do not meet the king's exacting standards.

King Vajiralongkorn was trained as a military officer and pilot and takes a keen interest in the armed forces, the main power brokers through much of Thai history.

He has a personal royal guard of at least 5,000 well-equipped and well-trained soldiers, and has presided over changes to troop deployments in Bangkok which appear to put more army units under his command, and shift others out of the capital.

Soldiers and police must keep their hair extremely short and on parade they must execute a difficult new salute, which involves puffing up the chest and jerking the head quickly to one side.

The king has received advanced military training and is a qualified fighter pilot

Under King Vajiralongkorn the much-criticised lese majeste law is no longer being used against perceived insults to the monarchy. But other repressive laws, like the sedition law and the computer crimes act, are being used against those judged too critical of either the military or the monarchy, and can carry long prison sentences.

Other causes for unease have been the mysterious removal of two monuments in Bangkok marking the end of the absolute monarchy after 1932, and the disappearance of five republican activists living in exile in neighbouring Laos, two of whose bodies were found, cut open, in the Mekong River.

There is no evidence linking these incidents to either the palace or the military government, but they are being seen by dissidents in Thailand as a warning not to question the status of the monarchy.

The king has taken direct personal control of the crown's vast assets, valued at well over $30bn (£23bn), and which under his father were always described as being held in trust for the nation, not the king.

He has installed his closest adviser, retired Air Chief Marshall Satitpong Sukvimol, who has served King Vajiralongkorn for 14 years, to run the Crown Property Bureau, and put army chief General Apirat Kongsompong onto the board as well.

But some assets have been sold, notably a controlling stake in the international Kempinski Hotel Group, thought to be worth around $1bn. The king is also reported to have taken more direct control of significant shareholdings in the two most important royal companies.

What he plans to do with these substantial funds is not yet clear.

The previous king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was the longest-reigning monarch in the world when he died

King Vajiralongkorn has also reclaimed royal properties in the old historic quarter of Bangkok which had been the site of important public institutions, like the city's oldest and largest zoo and the national parliament, which now have to move.

Again, it is unclear what his plans are for these strategic parcels of land.

Officially the monarchy is enshrined in a position above politics. In practice, its influence has often been significant, sometimes decisive.

King Vajiralongkorn showed a willingness to intervene in areas that mattered to him early on, throwing the military government into confusion when, on the death of his father in 2016, he refused to take the throne for six weeks.

He insisted on changes to the new constitution brought in by the military government in areas defining royal powers.

But his most dramatic intervention was in February this year, when he issued a royal command effectively forbidding his older sister from running as the prime ministerial candidate for a political party backed by the exiled former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

Mr Thaksin, whose parties had won all the elections held in the last 20 years, may have hoped the star quality and royal status of Princess Ubolrat would give his side an unassailable advantage in this year's election.

Princess Ubolrat made an unsuccessful bid to enter politics this year

That the palace intervened so late, only after she had announced her nomination, after weeks of rumours, gives weight to the claim by some in Mr Thaksin's camp that she had at least a tacit endorsement from the king, and that it took intervention by the military to change the king's mind.

The notion of King Vajiralongkorn aligning the royal family with Thaksin Shinawatra, the nemesis of the military and conservative royalists and Thailand's most successful election campaigner, would have turned Thai politics on its head.

There were rumours some years ago of a close relationship between Thaksin Shinawatra and the then crown prince. But that notion has been scotched by recent events.

The party was dissolved, significantly weakening the pro-Thaksin alliance. The king followed this by publicly stripping Mr Thaksin of his royal decorations, and making an unprecedented statement on the eve of the election calling on Thais to vote for "good people", a phrase understood to refer to anti-Thaksin pillars of the royalist establishment.

Thai people wear yellow on special occasions related to the royal family

The king's relationship with the military junta which seized power five years ago is harder to assess. The generals are intensely loyal to the monarchy.

The Thai armed forces and the royal institution have built a symbiotic partnership over the past 70 years of coups and Cold War conflict. Each needs the other.

But King Vajiralongkorn has discomfited the current military rulers by some of his actions, and is actively promoting officers who may be seen as their future rivals. His palace has become a distinct source of power in Thailand, an opaque and unquantifiable one.

The coronation was to be followed almost immediately by the announcement of the final result of the 24 March election, and the formation of a new government.

Already there are clear signs that the much-criticised Election Commission, a body picked by junta-appointed lawmakers, will act in ways that weaken the representation of opposition parties in parliament.

If, as predicted, the pro-military party is able to form a government, expect loud complaints from Thais unhappy about the judicial harassment of opposition parties and the contentious seat allocation system used by the commission.

Few people believe the long-awaited and much-delayed restoration of an elected government will end the political polarisation of the country.

After he placed the Great Crown of Victory on his head, King Vajiralongkorn stated that "I shall continue, preserve, and build upon the royal legacy and shall reign with righteousness for the benefit and happiness of the people forever".

But how will he approach the messy, post-election environment? At one time Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn was thought to be uninterested in many of the affairs of state, that he might be a hands-off monarch. His actions as king, however, have shown him to be keenly concerned with redefining royal power, and with the success of his reign.

Will he continue the close partnership with a military that wants to remain at the heart of political power, or might he encourage parties promoting reform and a more liberal political climate?

One quality of the new king has shone out these past 30 months - his unpredictability.