Indonesia election 2019: Why did so many officials die?

- Published

Indonesia held presidential, national and regional elections last month in one of the biggest voting exercises held on a single day anywhere in the world.

Now questions are being asked as to whether a deadly price has been paid for this - in the lives of election officials, more than 500 of whom are reported to have died during the vote and in the following days.

Media reports say the burden of organising and counting the votes led to exhaustion and death for some of the seven million or so workers who took part.

But were the deaths above the average that would be expected in Indonesia for this group of people had there not been an election?

How many officials died?

The vote on 17 April was a huge logistical exercise with more than 190 million voters taking part in a country made up of 18,000 islands and covering nearly two million square kilometres.

The Indonesian election commission told the BBC there were 7,385,500 personnel involved in running the poll, of whom 5,672,303 were civilian workers.

The rest were security personnel guarding polling stations.

All the counting was done by hand, and reports suggest it often continued through the night and into the next day to meet deadlines.

By 28 April, the election commission said that more than 270 of these election workers had died from overwork-related conditions..

It also said another 1,878 had fallen ill.

This death toll was subsequently revised upwards to more than 550.

Was the death toll higher than expected?

With more than seven million people involved in the poll, you would expect a significant number to die during the poll in line with national death rates.

The question is: was this number higher as a result of the election?

Well, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), Indonesia has a death rate of 7.16 per 1,000 per year (2017 data).

So applying that death rate to the figure of seven million election workers, you would expect around 137 people to die daily.

Let's assume that each election official was involved for four days - that would include any preparation, the poll itself and the subsequent counting.

Based on the national death rate above, you would expect around 548 people to die during this time.

This is pretty much exactly in line with the figure given by the Indonesian election commission.

Which groups were most affected?

This very approximate calculation does not take into account age, gender, health conditions or other factors.

The Indonesian authorities said that most of those who died were workers aged over 50.

So you would perhaps expect a higher death rate among election workers than for the overall population.

Continuing controversy

It is clear that the conditions under which election officials were required to work remains a matter of intense debate - despite there being no clear evidence that more died than would have been expected over a similar period.

In a report on election deaths, released by the Indonesian health ministry,, external it lists a number of health conditions which it says contributed to the deaths, including heart failure, strokes, respiratory problems, meningitis and sepsis.

We do not know how many of those who died had pre-existing health issues.

Of those admitted to hospital complaining of fatigue and stress, most had worked non-stop for 24 hours or longer to get their vote counts finished.

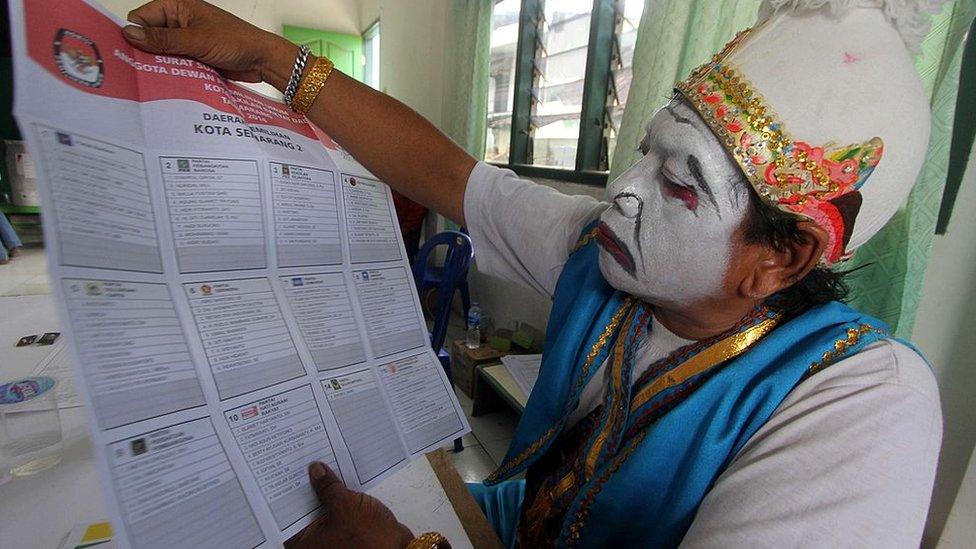

A Java election official holds up a ballot paper

Add to that the fact they may also have spent several days before the vote ensuring everything was ready.

The weather was hot in April. although not excessively so.

Jesse Hession Grayman of the University of Auckland says that while the number of deaths is unusual compared to the 2014 election when the death toll was 144, more work is needed before reaching a conclusion.

"It would need a detailed investigation of the demographic and health profiles of the election workers to see if the numbers fall within expected mortality rates," he told the BBC.

The controversy over the deaths has now sparked a debate about health checks being implemented in future for election officials, and the need for proper breaks and management of the workflow.

There have also been suggestions that Indonesia should look to other Asian democracies such as India and South Korea, where voting is staggered and technology is used to help record and count votes.

- Published18 April 2019

- Published17 April 2019