Lives lived and lost along Manila's Pasig river

- Published

The body of a man was recovered from the river by the coastguards

The Pasig river, which winds its way through Manila has long been a dumping ground for the Philippine capital's 13 million residents.

So bad was the pollution that in 1990 ecologists declared the river "biologically dead".

Award-winning clean-up efforts have meant some stretches are showing a return of aquatic life. But in the past few years a different kind of death has come to the Pasig. Local people say bodies are being dumped there with alarming frequency. They are victims, they suspect, of President Rodrigo Duterte's brutal war on drugs.

"Sometimes when we're sleeping, we would suddenly wake up because of a commotion," Regine told us.

She lives in Tondo, one of the most densely populated and poorest districts of Manila and for years, one of the most crime-ridden.

The Tondo neighbourhood has long had a high crime rate

She has grown up surrounded by violent crime. But she says that in recent years the community has also been a repeated target of "Oplan Tokhang" operations, the Philippine National Police codename for drug stings.

Her cramped and dark makeshift shelter has been repeatedly raided.

"They pointed a gun at us, they searched everywhere," she says of one raid. "My daughter was told to take off her clothes because they suspected that the drugs were hidden on her chest."

But as well as the raids, there is sometimes that other "commotion". Regine believes people are being killed in the neighbourhood and dumped in the Pasig river.

"The impact [on the water] sounded really heavy," she says.

"Then we would get up, but could not see anything floating. After maybe four days, we'd hear news that a body had been spotted."

Police in Manila routinely conduct drug raids but have also been accused of extrajudicial killings

And she says she has seen police officers carrying out a killing in Tondo.

"They shot the person once," she says. "They were not even in civilian attire but rather wearing uniforms. There were six policemen."

In this area, they call this "salvaging" - extrajudicial, execution-style murders.

Regine's allegation was corroborated by one of her neighbours, while five other people also told us they'd seen multiple bodies in the river - but said they didn't know for sure where they had come from.

But despite these testimonies, it is likely no-one will ever be held responsible for the many unresolved deaths in Tondo.

We put these allegations to the Manila Police District but they declined to comment.

The Philippine Coastguard regularly patrols the Pasig river. According to its records, it retrieved 36 bodies from it last year.

We were invited by the Coastguard Station Pasig to join them on an early morning patrol.

Coastguard teams conduct regular patrols along the Pasig river

It began with routine checks of private boat moorings, but after just 10 minutes, Deputy Commander Mizar Cumbe received a call: "There's a floating cadaver in the river," he told us.

We set off at high speed, passing Malacañang Palace - home to President Rodrigo Duterte - on the way.

About 3km (1.8 miles) further up the river the skipper shut off the engine.

Ahead of us was a bloated, naked body of a man face down on a rocky shoreline beneath an industrial estate. The body appeared to have red lacerations on his back and stomach.

"He's been in the water for two or three days because his body is stiff," Mr Cumbe told us, inspecting the scene from the patrol boat.

Another team of Coastguard officers put on rubber gloves and stepped gingerly over the rocks. Notes and photos were taken and then the body was heaved into a zip-up bag and moved to the nearby Pandacan Bridge to await a forensics unit.

Half an hour later, Jo Bautista of the Manila Police District arrived.

"Male, late 20s, no gunshot wounds," he declared. Two men from a funeral parlour loaded the body onto a stretcher and struggled up a steep bank to take it a morgue.

The dead man remained unidentified and was taken to a funeral parlour

The later autopsy report found the man had died of asphyxiation, but his identity remains unknown.

Mr Bautista said it can take months until bodies are collected by families, but most of the time they are left unclaimed. Unless someone comes forward to positively identify him, it is unlikely we'll ever know the true story of how he died.

In the Malacañang Palace, which faces on to the Pasig, lives the president, who has a hatred of drugs and a habit of joking about violent death.

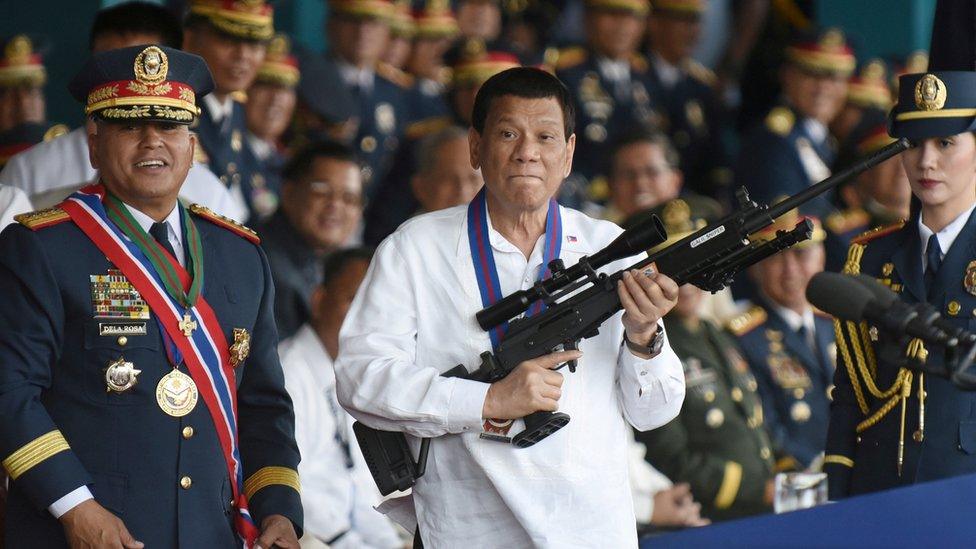

President Rodrigo Duterte has refused to co-operate with rights investigations

Rodrigo Duterte once warned drug dealers: "I'll dump all of you into Manila Bay, and fatten all the fish there."

In June, he entertained an audience of local government officials by recounting the time he forced a corrupt official to eat money or be killed.

"No-one would find out if the body is floating in the sea," he told the audience.

Mr Duterte came to power in 2016 promising a crackdown on the rampant problem with crystal meth, known locally as "shabu".

Duterte drug war: Manila's brutal nightshift

Urged on by the president, the police swept through predominantly poor communities, targeting drug suspects on lists compiled by local community leaders. For a while, nightly images of bloodied bodies splayed across roads and alleyways were broadcast around the world.

Police now put the number of people killed by them directly at 6,600. They argue all of the killings were in self-defence, after the suspects resisted arrest.

The president says crime in the Philippines has fallen 30% since he came to power, making streets and communities safer.

But human rights groups say the number killed in the drug war could be up to 27,000. They say many of the killings, including those carried out by vigilantes, were extra-judicial and therefore illegal.

The president's representatives always say his comments about murder are just jokes or hyperbole, not to be taken seriously.

But Amnesty International is among the rights groups saying killings on such a scale "do not happen by accident, but in pursuit of a state policy articulated at the highest levels".

Last year, Mr Duterte unilaterally withdrew the Philippines from the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court after it had announced a preliminary examination of allegations of "crimes against humanity" during the drug war.

A UN panel is putting together a comprehensive report into these allegations, and is due to present its findings to the Human Rights Council next year.

Mr Duterte, who has a well-known disregard for human rights groups, has said he will never be tried by an international body. I'll only "face trial in a Philippine court", he said, adding: "I will not answer [to] a Caucasian."

Meanwhile the Pasig river continues to be the last resting place for some of the victims of Manila's violence.

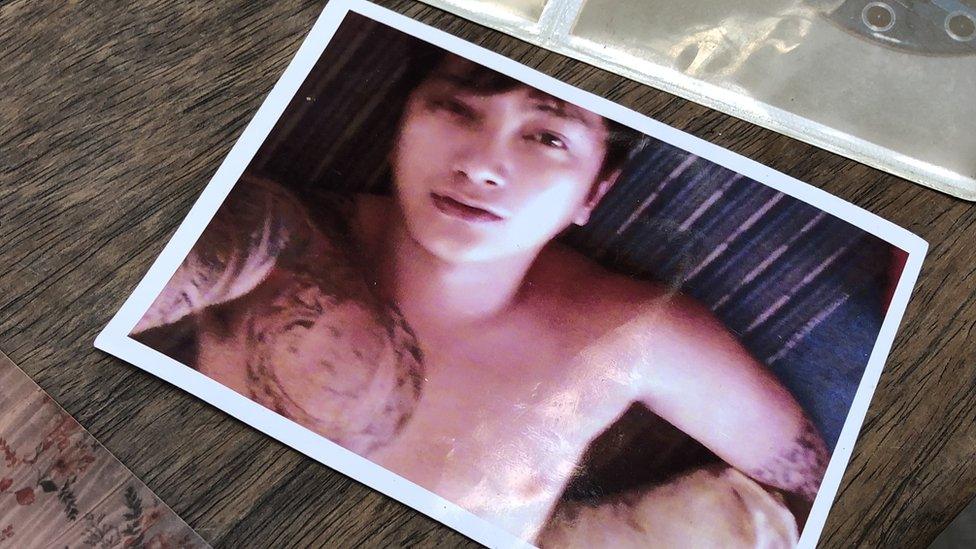

Harry's family identified him by his tattoos after his body was found in the river

In September last year, children from a slum in Tondo were scavenging for recyclable materials to sell when they dragged up a metal drum from under a bridge over the Pasig river.

Inside it was the body of Harry Lee Honra, aged 29. The drum had been filled with cement. His hands and feet were bound, his mouth had been gagged.

His family live in the Novotas area, nearby. His grandmother Flor Rivero helped bring up Harry.

She told the BBC he'd been a good child up until high school, but had become "lazy" and turned to drugs - specifically shabu - while hanging out with bad friends.

Harry's family say they may never know who killed him so they will "leave it to God"

Harry went missing on 20 August 2018. He'd gone to buy some fish, but when he didn't come home the family became concerned. Speaking to his friends the last they heard was that he had received a phone call and had gone to meet the caller. No-one knew who that was.

"He has tattoos of me, his mom, and his daughter on his chest," said Mrs Rivero. "If he didn't have those tattoos, we would never have know that it was him."

The family have no idea who killed Harry or why. Given the slow and inefficient justice system in the Philippines, Mrs Rivero isn't hopeful that the case will be solved, "we just leave it to God," she said.

Across town from Tondo is the Philippine Commission on Human Rights (CHR), an organisation Mr Duterte has been increasingly hostile to for its investigations into his war on drugs.

He has accused the organisation of political bias and threatened to reduce its yearly budget to just $20.

CHR's Karen Gomez says the growing list of deaths under investigation had become a "cause of serious concern" and that regional police stations are blocking or delaying the release of information in the public interest.

"This is something quite different about how we used to investigate killings in the past," said Ms Gomez.

"This time there is little or no co-operation when it comes to sharing documentation. There must be independent investigations on the killings or the deaths that have happened as a result of this culture of killing."

The massive rehabilitation centre for drug addicts in the Philippines

In her simple home in Tondo, Regine say she has become afraid to live in a place where neighbours disappear without a trace and bodies are dumped in a river along with the waste of the capital.

She fears the criminals and the drug dealers who operate openly in Tondo, but above all, she fears the people charged with fighting that crime.

"Even when the dogs are barking at night, I feel uneasy, thinking that maybe it's the police about to enter our home again," she says.

"I feel anxious whenever I hear keys jingling, because they come with guns for sure. I really feel scared."