Imran Khan: A year facing Pakistan’s harsh realities

- Published

For years, many doubted the former cricketing superstar would become prime minister

Imran Khan, the cricketing superstar-turned-politician, has had a turbulent first year in office.

It was a position that some thought he would never achieve: his 2018 election victory came after a two-decade long struggle, large portions of which were spent in the political wilderness.

And yet he persevered, brushing off allegations that the country's powerful military, which has ruled Pakistan on and off since independence, was interfering behind the scenes to the benefit of his PTI party.

This perception, and the myriad challenges facing Pakistan, has meant that Mr Khan's first year in power has been anything but smooth sailing. Critics charge that he has presented one face to the world and a very different one within Pakistan.

But what has he done?

Yes we Khan?

With an election campaign centred on populist, anti-corruption rhetoric, with a vow to usher in a "New Pakistan", Khan promised his supporters "Tabdeeli" (change) in an almost Obama-esque fashion.

His biggest challenge was to save an economy facing a balance of payments crisis.

Within the first eight months, he had made visits to long-time allies Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and China, securing $9bn (£7.3bn) in loans to shore up the economy. But the crisis refused to go away: growth continued to slow, the rupee plummeted and inflation rose beyond 10%, the first time it had hit double-digits since 2013.

With economic woes mounting, Imran Khan had no choice but to make a U-turn on his campaign promise that he'd rather die than seek an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In July, an agreement was reached with the IMF for a $6bn package, the country's 13th IMF bailout since the 1980s.

Uzair Younus, a South Asia expert at the US-based Albright Stonebridge Group, said that the biggest indictment of the PTI government's economic performance was its lack of policy planning.

"They have set very ambitious tax revenue targets but the moment they fail to meet those targets, the whole house of cards will come down," he said.

But Fawad Chaudhry, the Federal Minister for Science and Technology, told the BBC that the government was "doing our job".

"We have a dedicated team in place for economy and we are aware that the next elections will be dependent upon the state of economy," he said.

He conceded that economic conditions had meant the government had been able to provide little relief to the PTI's core middle-class voter base.

According to a BBC Urdu analysis, the Khan government has to date only achieved three out of 34 pledges made when it came to power. Mr Chaudhry singled out a new e-visa regime as a key achievement.

Diplomat-in-chief

In his first televised speech after winning the election, PM Khan offered his country's arch-rival an olive branch, declaring: "If India takes one step towards us; we will take two steps toward them."

To prove his point, he quickly ordered the development of Kartarpur Corridor, which represents a rare instance of co-operation between Pakistan and India and will allow Sikh pilgrims from India to visit a holy site in Pakistan.

But the conciliatory words did not last long. In February, the two neighbours came to the brink of war when India launched air strikes within Pakistan, aiming at what it alleged was a training camp for militants that had carried out attacks in Kashmir.

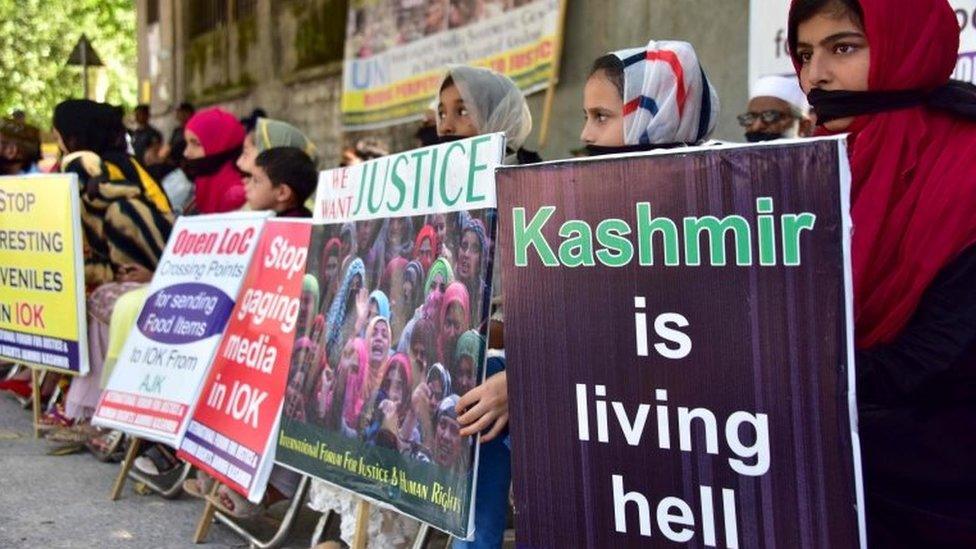

Kashmiri refugees in Pakistan-administered Kashmir take part in an anti-Indian protest

Pakistan then hit back, gunning down an Indian plane and detaining the pilot. Tensions soared but after 48 hours Imran Khan decided to release the pilot as a gesture of conciliation, earning plaudits and what appeared to be a diplomatic win over India's nationalist PM Narendra Modi.

Later in the year, against all expectations, the Pakistani leader shared great camaraderie with Russian President Putin whom he met in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

He then got coveted camera time at the White House during a visit in July where President Trump called him a "great athlete and very popular". While in Washington, he also met congressional leaders, gave interviews to the US media and said all the right things on the think tank circuit.

Donald Trump called Imran Khan a "great athlete and very popular"

But observers question what benefits have flowed from Mr Khan's charm offensives abroad.

"Will the US become friendlier with Pakistan and resume giving aid?" asked poltiical analyst Suhail Warraich. "Will Russia's behaviour change towards Pakistan on policy level? What are the substantial gains from these meetings?"

A crackdown at home

While portraying a progressive, and even endearing image of himself and the country during his foreign visits, the Imran Khan that Pakistanis see is a different political animal.

At speeches and public rallies, he is combative and often rails against previous governments, accusing them of corruption and bringing the country to the brink of disaster.

At the last count, at least 13 top opposition politicians are behind bars on charges of corruption, including three-time PM Nawaz Sharif, his daughter Maryam Nawaz and former President Asif Zardari.

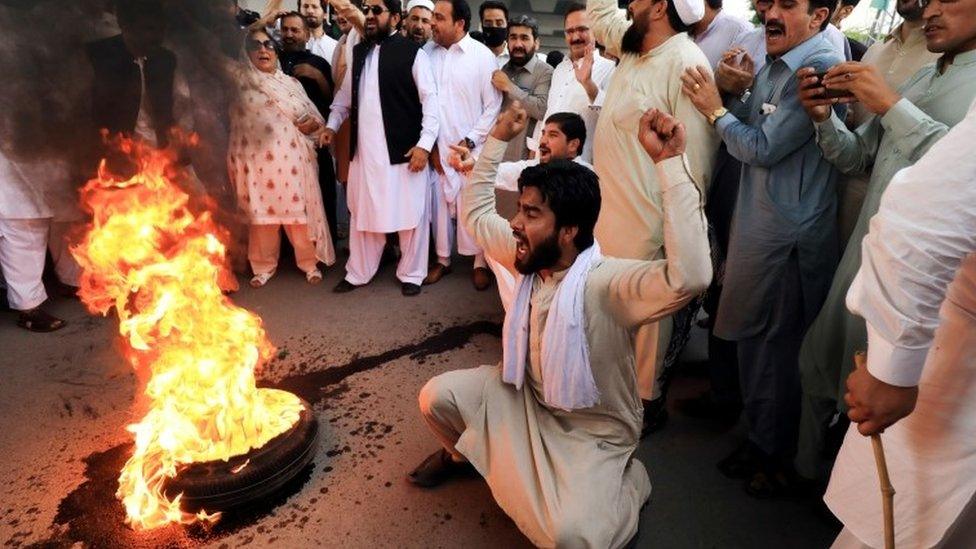

Supporters of the Pakistan People's Party protest against the arrest of former president Asif Ali Zardari

The Khan government is accused of hounding its opponents but insists it has no role in anti-corruption cases. "There is no witch-hunt," said Mr Chaudhry.

More ominously, say activists, there has been an insidious clampdown on freedom of expression and dissent since Imran Khan took power.

International press freedom group Reporters without Borders has complained of an "alarming decline in the state of press freedom in Pakistan" and asked Mr Khan to take urgent measures.

Reema Omer, a lawyer associated with International Commission of Jurists, said the government had been more oppressive than even its strongest critics had feared.

"Red lines on what can and cannot be reported are increasing by the day," she said. "The space for even questioning the government's narrative on certain issues is rapidly shrinking."

The power and influence of the Pakistani army

Professor Ahsan Butt, of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University, questioned whether Mr Khan - a man who long ago shed the image of a playboy liberal - was fully behind the crackdown.

"[The crackdown] has been primarily led by the military and intelligence agencies. Imran Khan has either been wilful participant in that or at worst; he has just looked the other way and not tried to stop it," he said.

Considering the historical imbalance between the civilian executive and the military establishment in Pakistan, some observers remain deeply sceptical about who is calling the shots. Army Chief Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa has just had his term extended for another three years, despite being set to retire in November.

"Imran Khan is in power with the help and blessings of the military and he knows that," said Professor Sameen Mohsin of the Lahore University of Management Sciences. "To that degree, they are indeed on the same page. I don't think he's really in complete control of decision making."

Such questions have dogged Mr Khan throughout his first year in office - and there is little chance he will be able to bat them away any time soon.

- Published28 July 2019

- Published2 June 2019

- Published7 February 2019

- Published1 March 2019

- Published29 November 2018

- Published1 February 2024