TM30: The form getting expats in Thailand into a bureaucratic tangle

- Published

Zareeka Gardner says she's reconsidering her decision to live in Thailand

Thailand has long been an attractive destination for Western expats - where money goes further and can buy a good quality of life. But the revival of an arcane immigration law has angered the expat community and got them questioning their freedoms in Thailand, as George Styllis reports from Bangkok.

"I've been made to feel as if I'm not welcome here," says Zareeka Gardner, a 25-year-old English teacher from the US.

She is one of the many foreigners living in Thailand who has ended up having to pay a fine because her apartment manager failed to promptly file a form saying where she was staying.

Thailand's Immigration Act contains a clause requiring all foreigners to let the authorities know where they're staying at all times.

Previously this job has been done by hotels collecting guests' details, or it was just ignored. But as of March, the government has been applying the law without compromise or exception.

Landlords must notify immigration authorities whenever a foreigner returns home after spending more than 24 hours away from their permanent residence - be it a trip abroad or even leaving the province. The same applies to foreigners married to Thais - their Thai spouse, if they own the house, must file the report.

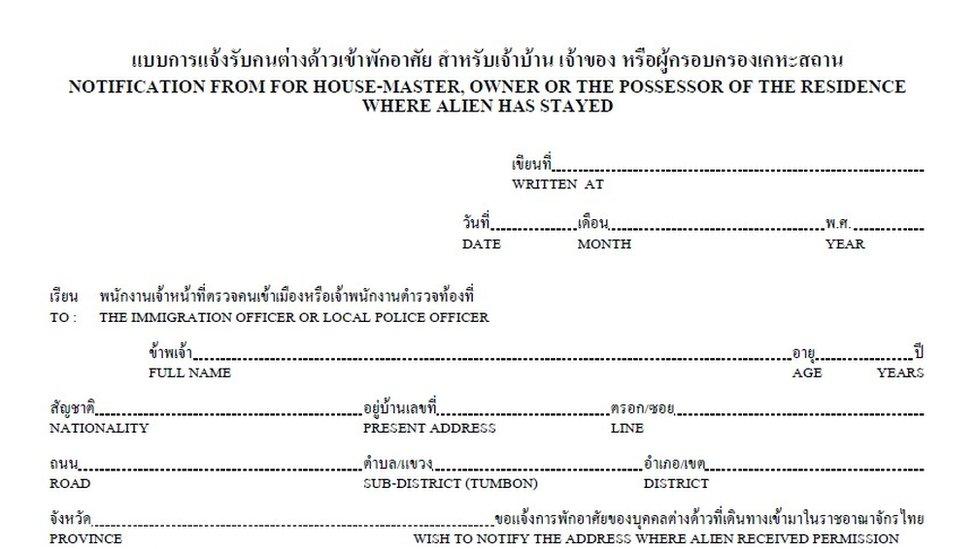

The form, known as a TM30, must be submitted within 24 hours of the foreigner's arrival or the property owner will be fined. If the fine for not doing so isn't paid - between 800 baht ($26; £21) and 2,000 baht - the foreigner will be unable to renew their visa or other permits. So they often, like Zareeka, end up paying themselves.

'It's too much'

The process has provoked confusion and consternation across Thailand, prompting caustic cartoons from local newspapers and outrage on social media.

The TM30 form is complex and must often be completed in person

Many have complained of inconsistencies between provincial authorities, and of landlords failing or refusing to fulfil their responsibilities, leaving tenants to pay the fine or risk losing their right to stay in Thailand.

There is an app and a website for the form, but many users have complained of trouble getting access or technical glitches. So they have to visit immigration offices, which can be an all-day affair with confusing forms.

Sebastian Brousseau, CEO of Isaan Lawyers in Nakhon Ratchasima province says he was inundated with questions after the law started being applied. He says the law is regressive.

"I have clients that were in Thailand before, that are leaving Thailand because they feel unwelcome," he says.

Foreigners residing in Thailand must already report to immigration every 90 days, an order known as TM47. Only those with permanent residency or a special visa are exempt from this and other orders.

"Already they felt it was a burden to fill in the TM47 and now with the TM30, for them, it's too much," said Brousseau.

He has now launched an online petition calling on the government to scrap the law. The petition has gathered nearly 6,000 signatures.

It's not just foreigners who are finding the mounting bureaucracy bothersome.

Suchada Phoisaat, a journalist and entrepreneur, lost a day's work doing the TM30 on her Russian husband's behalf at the immigration department.

"There were long queues - it was annoying. If foreigners or Thais have to do this, we just ask for a proper system to help us save time."

Why now?

The immigration law was introduced in 1979, when Thailand was trying to keep track of an influx of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees fleeing conflicts at home.

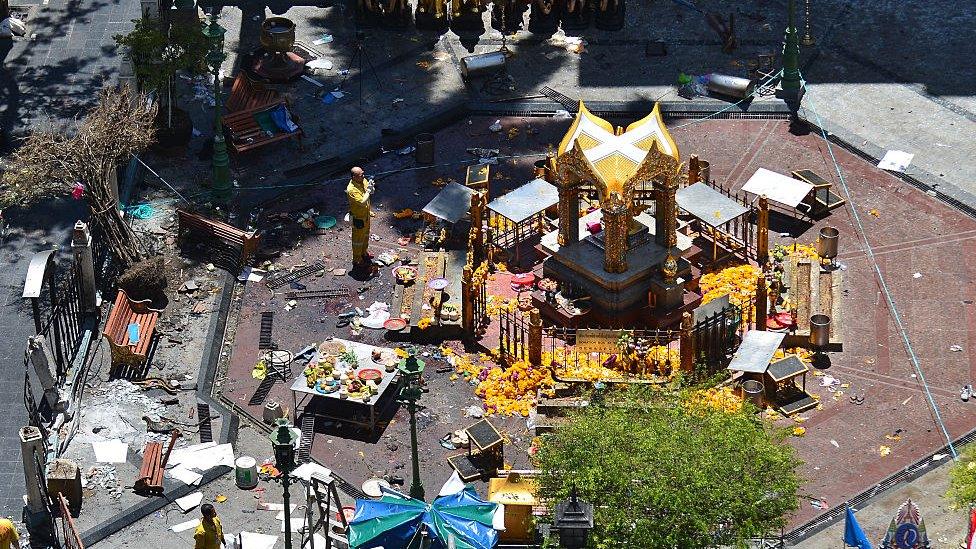

The 2015 attacks on a shrine in Bangkok shocked

Just why the government is enforcing the law now remains unclear since official reasons are flimsy.

Still haunted by the major terrorist attack in Bangkok of 2015, the government says it will help strengthen national security while protecting law-abiding foreigners. "Good guys in, Bad guys out," is its slogan.

Yet by responding to criticism with ways to shortcut the registration process, the government has often undermined its own argument, along with that of it forcing rogue landlords to declare their earnings. Such holes have left foreigners cynical.

Zareeka Gardner says she feels defeated by the system.

Coming from the bureaucracy of China, she felt Thailand would be an easier place to live. But lost in a thicket of vague and contradictory information, without help from her teaching agency, her perception soon changed.

Still without a work permit and hounded about it daily by officials, she has had enough and booked a flight back to China. During one immigration visit on another issue, she says, an official told her he would send police to visit every day "until you are gone".

"I went out and just cried for about half an hour," she says, adding that she knows people who have gone through worse than she has.

Analysts say the new policies could also deter foreigners from travelling around the country

The growing number of cases like Zareeka's comes at a worrying time for businesses heavily dependent on foreign labour and money. While international tourism should be relatively immune to the immigration law, domestic travel among foreigners is expected to dip.

The economy is already struggling, growing at its slowest rate in nearly five years in the second quarter, and aspirations for it to go digital will not be met with punitive immigration policies, says Amarit Charoenphan, co-founder of HUBBA, a co-working space and community.

Yet the government remains defiant, maintaining the law is necessary.

Speaking at a panel discussion last week at Thailand's Foreign Correspondents' Club, representatives of the immigration department conceded there had been technical problems with filling the TM30 forms online, but once addressed, the process should run smoothly.

But for foreigners like Zareeka, they're wondering if it's worth waiting.

"Sure, it's nice here, but with all the hoops we have to go through, is it really worth it?" she said.

George Styllis is a freelance journalist based in Bangkok

- Published16 April 2018

- Published17 July 2019

- Published16 August 2024