Tattoos in Japan: The eye-watering art thousands cross the world for

- Published

For Horimitsu, the sound of needles painting skin is a soft, rhythmic scratching, like a solitary cricket - "sha, sha, sha".

For 30 years he has tattooed by hand in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, needing nothing but ink and a needle-tipped stick.

By that hand, gods and monsters spring to life on the backs of bankers and band members. Koi carp leap over limbs.

And today, a jade-green dragon - a symbol of protection from flames - will flare on the arm of a young firefighter who flew thousands of miles to be here.

Kyle Seeley, 23, lies quietly on his back as the artist works, skewering his tricep with perfectly regular jabs. He's being inked from shoulder to wrist; a full sleeve with the great lizard set among peonies - the flower of good fortune and nobility.

Customer Kyle Seeley waits for Horimitsu to add colour to his tattoo

There are tattooists back home in Grande Prairie, Canada. But they don't have what he's looking for: the centuries-old Japanese art of tebori, or traditional "hand-carved" tattoos.

In the West, a longstanding fascination with this style has become a full-blown trend. Hipsters seek it out for the story: "I went to Japan to be hand-tattooed." For others, it's the lure of art that lasts.

"I've heard the colours from tebori stay way better and look more vibrant," says Kyle, who has machine-made designs on his chest, ribs and sternum.

"In Canadian dollars, it's 500 a session. (£300; US$374). So a few grand for sure. But I've been saving up for this."

Horimitsu, his tattooist of choice, has almost 63,000 Instagram followers and a big international following - including US singer John Mayer, who claims the artist gave him a grilling before finally agreeing to work on him: How did you find me? How do you know the person who recommended me?

His latest diary-filler is the Rugby World Cup, which Japan is hosting for six weeks from 20 September.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The overseas interest is a lifeline for this ancient artform, as local enthusiasm has waned recently. Young Japanese often prefer Western-style geometric tattoos with a focus on fine detail.

Tebori artists typically take more control of the creative process, and some will only ink those they choose.

Kyle is clearly on board with this. He walked in today with no idea what colour his new dragon would be. "This is Mitsu san's art style, and whatever he thinks would look best, I wanna go with," he smiles.

He shows no signs of pain as a stick with a row of needles at its end pushes colour under the top layers of his skin. Every 10 seconds, Horimitsu turns to dip the tool in ink.

It looks like it would hurt ridiculously, but aficionados say tebori is gentler than bone-shaking machine work.

So on a 1-10 pain scale?

"A three or a four?" reckons Kyle. "Yeah, it's way better."

Tattoo artist Horimitsu at his studio in Tokyo

John Mayer says he found himself "hallucinating beautiful, brilliant hallucinations" during his time with Horimitsu.

When I ask if there's a post-tattoo endorphin rush, the artist nods emphatically.

"Dopamine, adrenaline… I see a lot of customer, after tattoo… it's too much exciting! They lose wallet, passport, spend a lot of money…"

'Sporting events bring good business'

Ahead of the Rugby World Cup, players and fans were urged to cover their ink to avoid giving offence, as many here associate tattoos with the yakuza, Japan's mafia. But for some fans that warning proved more of an inspiration, and they'll be fitting two-hour tattooing sessions in around matches.

Many find Horimitsu through Mike Derbyshire, whose website Pacific Tattoo Co connects English-speaking clients with Japanese artists.

"We've got one Welshman right over that time period," he says of the rugby.

Dragon, presumably?

"I think it might be actually…!"

Sporting events always bring good business, he says.

"I'm noticing a real correlation - like the [Tokyo 2020] Olympics next year, we've had people asking for the last year or so to book in over that time."

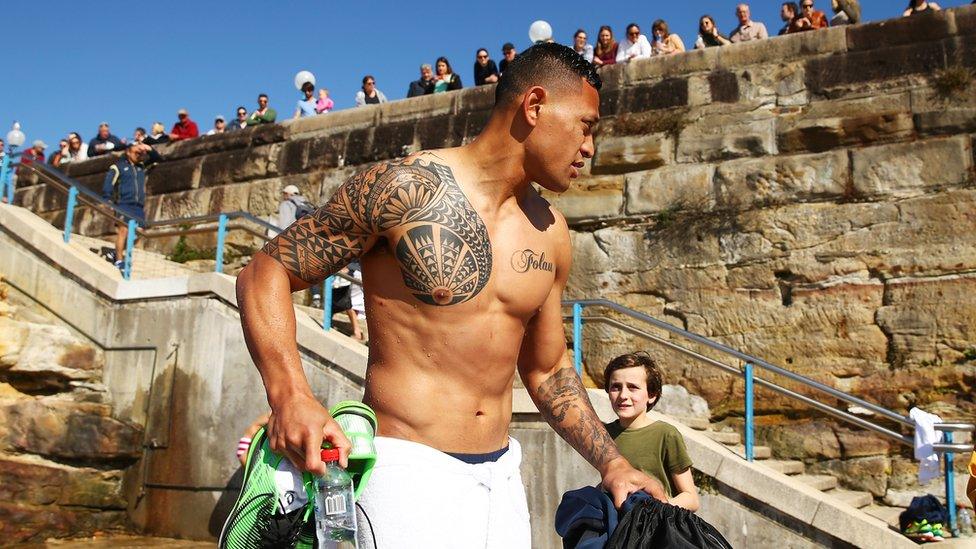

Customers frequently fly across the world to be tattooed here

Some 60-70% of Horimitsu's clients come from outside Japan, and other tebori tattooists report the same.

"We've had guys from Germany, we've got guys from the UK all the time, a lot of Americans… A lot of military staff from US bases," Mike says.

"Business hasn't been great for Japanese tattooists in Japan for the last little period, unless you've been able to crack the communication problem."

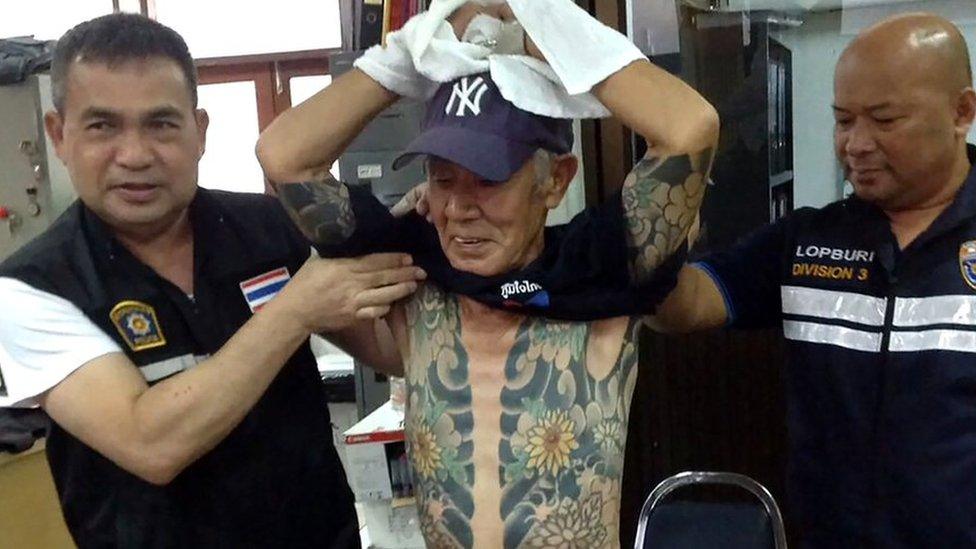

Part of the issue is a loss of customer base. After the Second World War, Japanese tattoos (known as "irezumi") were strongly tied to Japan's yakuza crime gangs. For decades, mobsters got tattoos to prove their courage, flaunt their wealth, and identify themselves to other yakuza.

Horimitsu learned his craft through a Japanese tattooing "family", where several young apprentices serve a master, often for many years, in a strict feudal environment.

He says the world of irezumi was "violent sometimes. Scary. Before our customers were only yakuza. Until 10 years ago".

Now Japan has hardened its stance on the gangs, and a police crackdown has squeezed yakuza membership from a peak of 184,000 in the early 1960s, down to 30,500. Those who remain want to fly under the radar, which means no big identifying marks.

Yakuza members display their tattoos during a festival in Tokyo

"Some young people still join the yakuza, but they are new generation - smarter than before," Horimitsu says. "They don't get tattoos. Their business is more sophisticated. [Happens] after golf…"

In the old days, he says, clients would start a huge back piece and get sent to prison, only to return a decade on to have it finished.

Asked how he greeted them, he smiles mischievously: "Oh, welcome back! You seem old!"

'No pools, no gym, no hot springs…'

Sadly for tattoo fans, social attitudes in Japan haven't caught up with the fact most yakuza don't want ink these days.

In law, it's been a grey area since 2001, when Japan's health ministry decided to class tattooing as a medical procedure - meaning any tattooist who wasn't also a qualified doctor was suddenly operating illegally.

People with tattoos are often banned from using public gyms, swimming pools and onsen - Japan's hot springs. Visible body art can also damage your job prospects in professions like teaching or finance.

Kyle, who as a cheery blonde Canadian couldn't look less like a Japanese gangster, still got hit by the ban.

"Even at my hotel. I was gonna go to the swimming pool and it was like - uh-uh - there's a sign: 'No tattoos.' I don't speak Japanese. But I still notice on the subway if I'm wearing a T-shirt, people stare at my arm."

Though it looks gruesome, Kyle describes the pain of tebori tattooing as a three or four out of 10

Facing negativity at home but a rock-star reception elsewhere, some tebori tattooists take their skills overseas.

Kensho II, who received his professional name from his master, lives in Amsterdam.

He says clients there value the hand-crafted approach, and come prepared to be patient: A full back piece can take 70 hours or more, depending on skin type, body size and design.

"Dragon is most requests I get," he says. "I like make it, never boring. Japanese dragon has a lot of story and meaning. Each folklore is different."

Though he has left Japan, Kensho II holds fast to tebori traditions.

"All my tebori instruments [are] made by myself. I believe in one of the teachings of Shinto [the ancient Japanese religion], "musuhi", which means all human-made things have a soul. Tebori instrument is part of my body and soul for me. That's why I never sell my instruments."

Tattooist Kensho II says Japanese-style dragons are a popular request

Just as Horimitsu praises his master Horitoshi - "74 and still working - crazy!", Kensho II speaks of his own with reverence.

"When I started as an apprentice, I was always watching his technique, researching the story and meaning of each subject from old book, drawing a lot. I slept only two-to-three hours a day for three or four years, 'cos I must learn many things.

"Our rules were, 'do not ask, do not say no, and do not say your opinion. Must follow master's order. Be humble, study hard. Respect other culture.' Master never explain it, you need to understand by his face changing and tone of voice. Otherwise [you would be] punished physically by older apprentice so you can understand anyway."

Horimitsu says he was invited to learn tebori aged 20 only after visiting his master several times, being tattooed by him, and bringing a symbolic gift:

"I brought two sake bottles. One is no good. Two - is a Japanese traditional style. Two tied with rope. It means, I want to connect to you."

His training took more than a decade.

Kensho II was tattooed by his master before becoming his apprentice

On the day I meet Horimitsu, the needle-stick (or "nomi") he's using is one that belonged to his master. The apprenticeship, he notes, really lasts until death.

'Change is coming…'

Some commentators have predicted that Japan's conservative attitude to tattoos could soften with the arrival of thousands of inked foreigners for the Rugby World Cup and Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

As an outsider who's made a study of Japan, Mike Derbyshire believes the chance of a sudden shift is minimal.

"It would have happened a hundred times over already.

"If it's gonna happen, it's going to be the younger group right now getting into Western-style tattoos in emulation of Western popular culture, and it'll creep in over time.

"Go to Harajuku [the hub of Tokyo's youth subcultures] and look at the fashion ads - they're covered in Westerners with tattoos. It's everywhere.

"I think it's starting to shift at the moment. The beginnings of the change are happening. The question will be: will [the government] try to clamp down on it aggressively?"

Harajuku, Tokyo: The barometer of style in Japan's capital

More on Japanese tattoos...

- Published20 September 2018

- Published20 September 2019

- Published11 January 2018

- Published22 May 2016

- Published1 February 2017