Viewpoint: Qandeel Baloch was killed for making lives 'difficult'

- Published

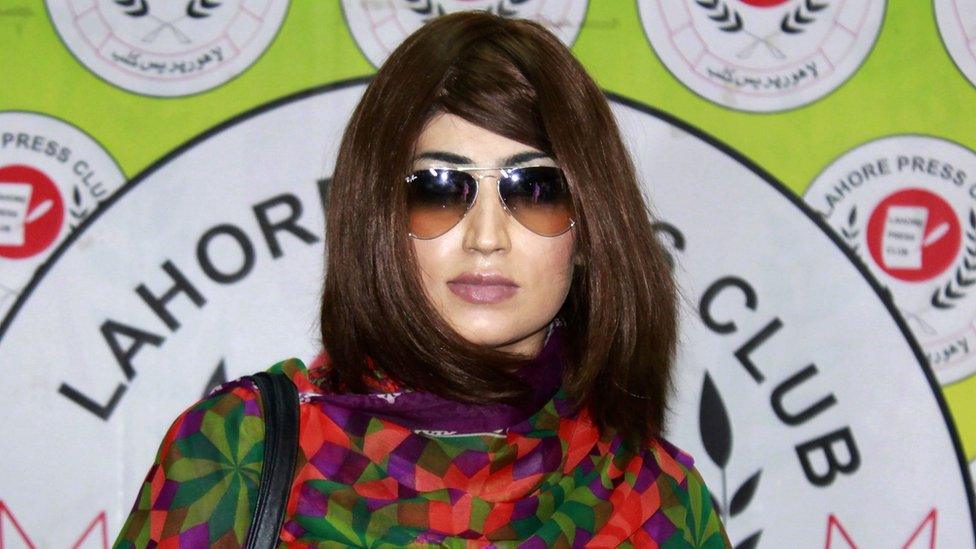

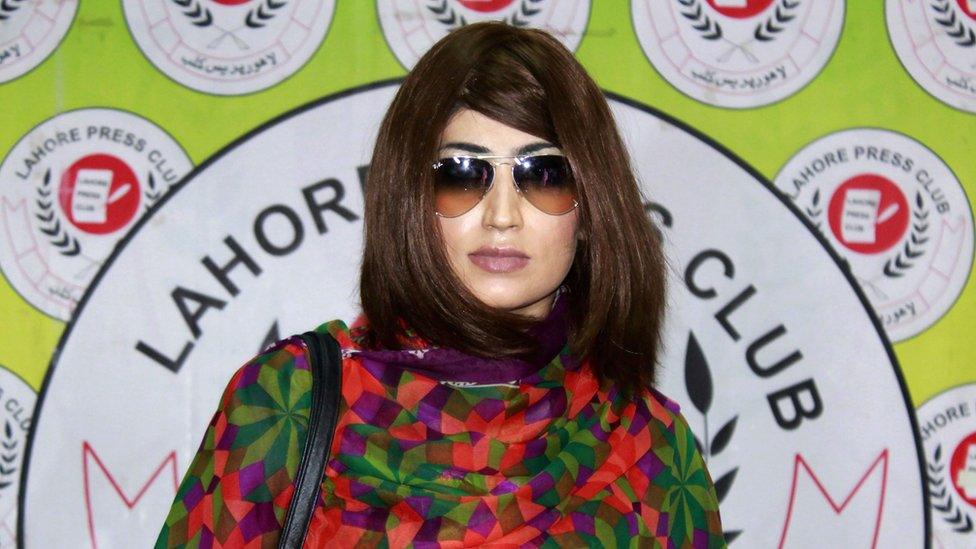

Qandeel Baloch challenged Pakistan's conservative society with her videos

The murder of Pakistan's first social media star Qandeel Baloch prompted instant soul searching in the country and made headlines around the world. Her brother has now been sentenced for killing her but the roots of this tragedy can also be traced to the judgement and scorn of her lifestyle in Pakistan, writes journalist Sanam Maher who has followed Qandeel's story for years.

Last Friday, one of Pakistan's most well known murder cases came to a close after three years.

The country's first celebrity-by-social-media, Qandeel Baloch, was killed at the age of 26 by her brother in July 2016. It was a so-called honour killing - he felt that the videos and photographs she had been posting online brought disrespect to their family.

After he strangled his sister at their home in Multan while their parents slept, Waseem returned to their ancestral village of Shah Sadar Din, a little over two hours drive away, where he made no effort to hide.

According to many reports, he was spotted riding around on his motorbike in the village's main market the morning after he killed his sister. He needed people in the village to know what he had done.

In the days before the murder, a newspaper had published images of Qandeel's passport, revealing that her real name was not in fact Qandeel but Fouzia Azeem.

Her followers learned that she came from a village in rural Punjab, from a house with dirt floors, and she was not, as she had claimed, the daughter of a rich landlord.

The day after he killed Qandeel Baloch, her brother rode about the village apparently unashamed of his action

When I travelled to Shah Sadar Din in October 2016 to report on the murder, I met with villagers who told me that they were disgusted when the news of her true origins broke.

"Your sister is singing and dancing in her knickers and you're living a luxurious life with the money she earns," one man told Waseem. "You have no ghairat (honour)."

When Waseem was arrested the day after the murder, he was presented at a press conference where journalists asked him why he had killed his sister.

"The reason is the way she was coming on Facebook," he replied simply.

Attiya Jaffrey, the lead investigator on the case, told me that Waseem confessed to her: "She made our lives very difficult and I had no other solution".

Waseem has now been sentenced to 25 years in prison, but five other suspects, including Mufti Abdul Qavi, a cleric, were acquitted.

In June 2016, Qandeel publically accused Mufti Qavi of behaving inappropriately with her during a meeting at a hotel.

In a press conference held shortly after, she pleaded with the government for protection, saying that she was receiving threatening phone calls and messages, saying she had "exposed" the cleric for what she claimed he truly was: a hypocrite who used Islam to further his interests.

When news broke of Qandeel's murder, a television channel asked Mufti Qavi for his reaction.

"In the future, before you humiliate the clergy, you should remind yourself of this woman's fate," he warned.

Mufti Qavi's role in Qandeel's life and death has been controversial

On Friday, Mufti Qavi was acquitted of playing any part in her murder and as he exited the court he was showered with rose petals by those who felt it was a step too far to even indict him.

However, many others took to social media to voice their dismay at the court's judgement.

"It is now proven that a mullah will always escape punishment irrespective of the crime," tweeted journalist Mubashir Zaidi.

"This verdict offers an empty, dissatisfying closure," said another journalist, Amber Rahim Shamsi. "The lesson is that the powerful and influential… are never held responsible."

When I met Mufti Qavi in 2016, he was at a low point: he had been left out in the cold by his political party (Imran Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf), unceremoniously removed from a religious committee and he was the butt of jokes in the press.

The police had been investigating whether Mufti Qavi directly or indirectly, through his supporters, encouraged Qandeel's brother to kill her.

In the crush of reporters outside the court on Friday, Mufti Qavi said he had been vindicated. "The prayers of my supporters have been met," he said. "It is a day of justice, of victory."

Could one woman's word, I had wondered in our meeting three years ago, threaten a man's privilege and status? I got my answer this Friday - no.

"They did not have a single witness who spoke against me," Qavi said.

There's no doubt that Qandeel was provocative and indeed many of those who mourn her today drew courage from this at the time.

Fatima, a 25-year-old journalist I met in Multan in 2016, told me that she started following Qandeel on social media after she watched a video of her swimming in a pool where men were present. It was a small way to thumb her nose at those who said she was immodest. "She was a baghi (rebel)," Fatima said.

Qandeel's photographs and videos became more risqué - for conservative Pakistani society - as her fame grew and hateful comments would follow within moments of her posting them.

Qandeel Baloch had a reputation for being Pakistan's first social media celebrity

"If I find this woman alone, I would kill her right on the spot and would hide her haram (forbidden) body," one comment on Facebook read.

She confused her critics. How could she continue to behave the way she did? What kind of woman did not feel shame?

A man in Shah Sadar Din who sympathised with Qandeel - and did not want me to name him for this reason - told me that when I wrote about her, I should not call this an "honour killing".

"This woman was not murdered in the name of honour," he said. "She was murdered because of people's judgement." When Waseem strangled Qandeel, he was trying to silence that judgement.

What followed was praise: "Qandeel Baloch was a disgrace to Pakistan," a woman tweeted when news broke of the killing. "She's certainly gonna suffer in hell. Her brother did well."

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that nearly 1,100 women were victims of honour crimes in the year preceding Qandeel's murder.

They had stepped out of line: had a relationship, married of their own free will, had an argument with their husband. Sometimes they were killed because someone merely suspected them of doing these things.

If their stories made it to the newspaper, they were usually buried within the pages inside in a small paragraph. But millions had seen Qandeel's transgressions. She had behaved badly, and what was worse, her critics said, was that she didn't seem to care.

"Shamelessness and exhibitionism are a scourge in our society, spread through women like her," said Maulana Fazlur Rehman, leader of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam religious party.

In Shah Sadar Din, there was relief. "One who seems without honour or self-respect can discover it at any time," they said.

Qandeel's parents told me that she had promised her brother that she only needed a little bit of time before she quit the work she was doing.

If she had, if Waseem had given her that chance, would she have been praised for rediscovering her ghairat (honour)?

When the verdict was announced, this is one of the first tweets I saw: "This bitch got exactly what was coming to her."

Honour crimes seek to strengthen a social code by brutally punishing those who violate it. The court's verdict on Friday draws a neat line between victim and suspect. Perhaps that is why it feels like it falls short.

A parallel justice system exists, a court of public opinion. And there, the question remains: how complicit is this society in this killing? The jury is still out.

Sanam Maher is a journalist based in Karachi, Pakistan and the author of the book, A Woman Like Her: The Short Life of Qandeel Baloch.

- Published22 August 2019

- Published27 September 2019