Karachi Biennale: Price of speaking out against police killings

- Published

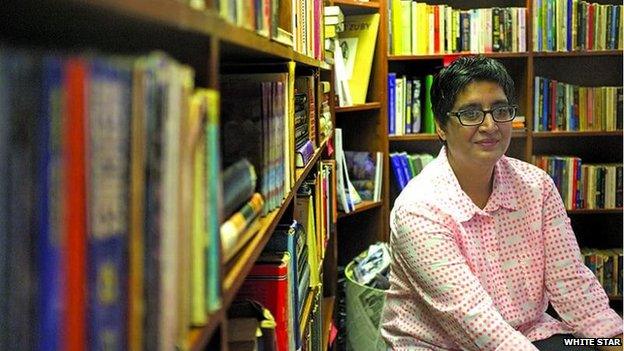

It took only a matter of hours for the two plain-clothed men to arrive and demand Adeela Suleman close her exhibition. It took another two days for unnamed men to completely destroy it.

Suleman was taken aback: yes, the 440 headstones she had carefully assembled in and around the hall in the Pakistani city of Karachi were supposed to evoke emotion.

And yes, the subject matter was controversial: each of the headstones represents a person killed by one of the country's most notorious police teams.

But now The Killing Fields of Karachi - her entry into the Karachi Biennale that was supposed to be a comment on extrajudicial killings - has become a flashpoint for freedom of expression, and the fight to be heard.

"The state officials have done what they wanted to do," Suleman told BBC Urdu. "They have closed the exhibition.

"I learnt one thing: that art has so much power, that in two hours of the public opening, something, somewhere didn't like that this is happening. That really scared them, to the extent that they had to break each and every pillar, they had to remove it."

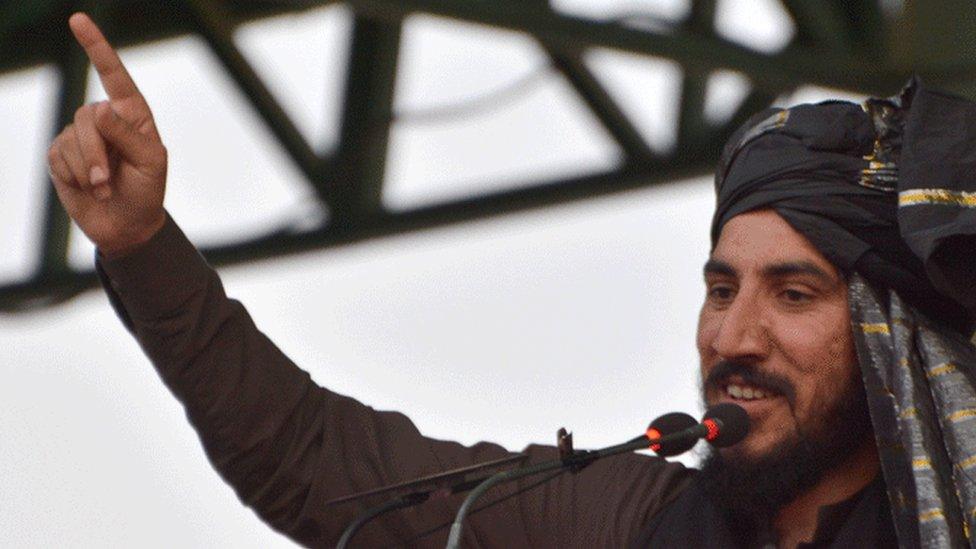

'Killing machines'

The topic was always likely to provoke someone in power. After all, you don't need to look far in order to find examples of people killed by Pakistan's police.

At the start of this year, there was the family shot dead by officers as they made their way to a wedding. Just four months earlier, a 10-year-old girl had been killed in the crossfire between officers and a street mugger.

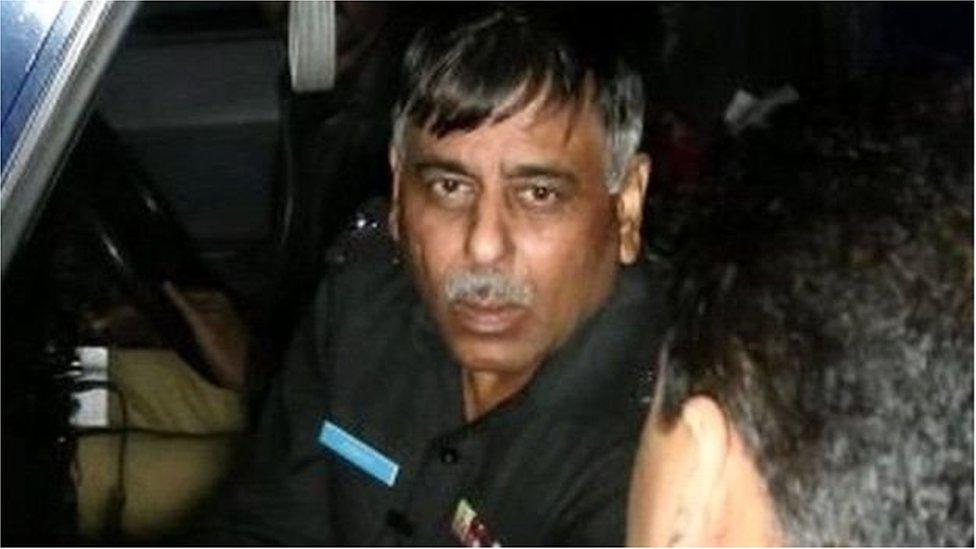

Suleman had chosen to focus on one very particular set of so-called "encounters": those linked to a man who was once one of Karachi's top police officers, Rao Anwar.

According to official police records, his team killed 444 people over the course of seven years. There is some suspicion Anwar may have made a living from staging extra-judicial killings of men wanted by the security establishment.

What is clear is that, as one unnamed police official put it to Pakistan's Dawn newspaper, Anwar had "led a team of killing machines", external which went unchecked for years.

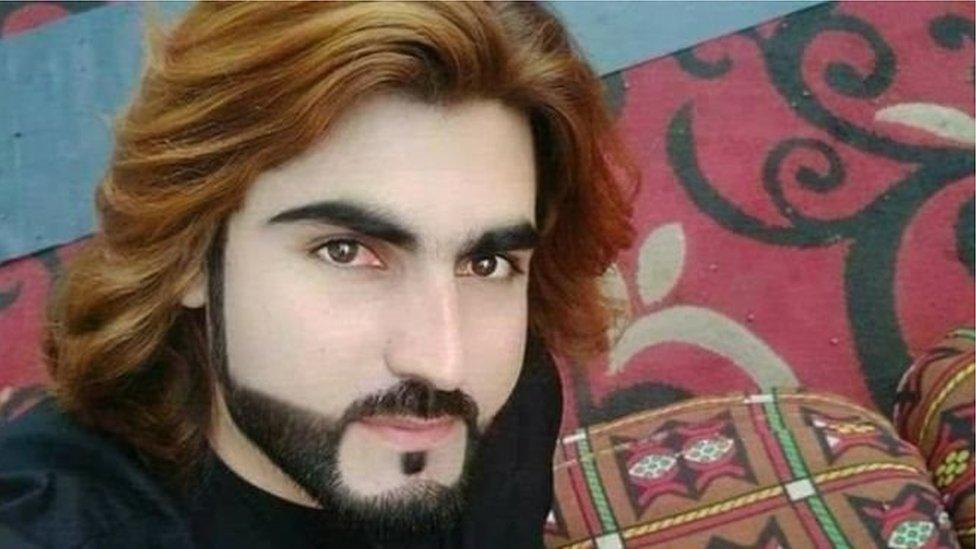

But Anwar's role in the killings in Karachi really hit the headlines after a young man called Naqeebullah was killed by police in an alleged "staged encounter". He was, they said, a terrorist. His family said Naqeebullah was no such thing. In fact, he was an aspiring model and this was a "fake encounter".

Rao Anwar's methods were criticised but they appear far from uncommon

The case caused outrage: Anwar was removed from his job, while a police inquiry found Anwar guilty of murdering Naqeebullah and others. He has not been tried in court and denies the charges against him.

It was Naqeebullah's death which inspired Suleman, as well as prompting wider protests against the treatment of the ethnic Pashtun community he was from., external

"Naqeeb's case was one case which really shook the whole world, not because that policeman was involved, but simply because he was a young, beautiful 27-year-old man," she said.

"It really made us question what kind of a society we live in. I think it stayed with all of us."

The result was her entry to the biennale: the tombstones, and a short film where she - with the help of Naqeebullah's bereaved father - tells the story of his death.

Naqeebullah's death sparked protests in Karachi

"There was nothing in the film or in the installation which was not out their in the public," she explained to the BBC. "I was working with the father, I was playing with emotions, I was questioning as the viewer, where should I go, what am I looking at. We as viewers, are we the perpetrators because we are not doing anything?"

She did not foresee any backlash. She was wrong.

The men arrived within hours of Sunday's opening, demanding it be shut. The head of the city's parks department came out and described the work as vandalism. By Monday morning, the gravestones which stood outside the hall - and therefore could not be locked away - were on their sides.

Suleman's supporters came and lay down beside them - an act of defiance against the as yet unidentified groups which had taken such offence.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

By Tuesday morning, the stones had been smashed to bits. Suleman says it was the security services, but there has been no official comment.

It didn't take long for the organisers of the Karachi Biennale to decide the exhibit was no longer something they could back. They released a statement saying it was "not compatible with the ethos of #KB19".

"We feel that politicising the platform will go against our efforts of bringing art to the public and drawing artists from the fringe to the mainstream cultural discourse," they added, pleading for understanding.

That understanding is, however, in short supply from Karachi's artist community. The organisers, they say, have abandoned their artist.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"It's very simple. The work was vetted by the curatorial committee. Seen by the jury. Allowed to be shown to the public. If there was anything that did not adhere to the concept... people should have not allowed it to go forward," Sameera Raja, the founder of Karachi's Canvas Gallery, told the BBC.

"However, once it is allowed, under the ambit of KB, then KB cannot abandon their artist. This is not about Adeela or a particular work. This is not only about freedom of expression. It is about owning up, taking responsibility and respecting the artist and the community at large."

Marvi Mazhar, an architect and urban planner, warned of the chilling effect it will have on future installations - especially at a time when other industries are finding themselves fighting against increasing censorship.

"The whole order of taking No Objection Certificates will now be vetted through censorship, and every public artwork will now go through scrutiny. Now every artist will have this insecurity of some work which will not be accepted and this insecurity is what I am really questioning - how does the state work with the notion of art?"

But it the authorities are going to insist art is removed from politics and comment, they are going to have a problem, Suleman says.

"The moment you make art you are political, the moment you put it out in the public space you are political," she shrugs.

However there is one thing which has given Suleman hope for the future of Pakistan's art scene in the last few days: the number of people who have come out in support of her work.

"I am not alone. I think I have more people with me than before. I am not abandoned at all," she said.

- Published29 July 2015

- Published24 April 2015

- Published23 April 2018