Taal volcano: Can we predict eruptions?

- Published

Time-lapse of lightning storm swirling round Philippine volcano

A volcano in the Philippines might erupt "within hours or days", warn authorities.

The Taal volcano has started spewing lava and has released a huge plume of ash, triggering the evacuation of 8,000 people from the area.

So how good are we at predicting when a volcano will erupt and how severe it will be?

A volcanic eruption is when steam or lava is released from a volcanic vent.

It can be notoriously difficult - with devastating consequences - to know when an explosion might happen, especially when a volcano has been dormant for many years.

However, scientists can look for particular signs and trends to make predictions.

They monitor the activity of volcanoes by looking at:

earthquakes

emissions of gases

inflation or deflation of the volcano

If scientists start to see an acceleration of gas from volcanic vents or nearby tremors, for instance, they may start to get concerned about an eruption.

However, predicting whether those signs indicate an eruption will be in one hour, a month or even longer away depends on the individual volcano.

The more data volcanologists have on a specific volcano, the better they'll be able to anticipate its behaviour and the possibility of an eruption.

Most volcanoes tend to show these signs in the weeks or months prior to an eruption but some explosions are much more sudden and unexpected.

It's also more difficult to judge eruptions when volcanoes have been dormant for a while or were active prior to the introduction of modern monitoring technology.

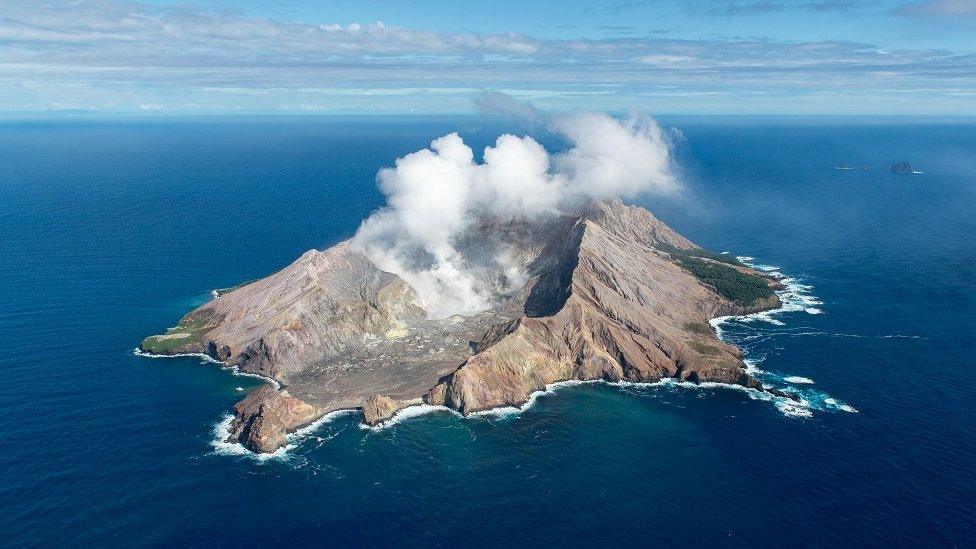

White Island volcano in 2016

In 1991, an estimated 5,000 lives were saved through an evacuation of the area surrounding Mount Pinatubo, in the Philippines.

On that occasion, advance warnings of an eruption were made by the US Geological Survey and Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology.

They monitored the increasing activity from about 10 weeks prior following a series of smaller explosions and alerted the authorities to the need for a major evacuation effort.

It was one of the largest eruptions of the last century.

The Tungurahua volcano in Ecuador erupting in 2016

However in other instances, such as the eruption of Mount Ontake in Japan in 2014, there was no alarm raised because of how sudden it was.

There have also been times when people have been removed from an area unnecessarily - when an eruption didn't actually happen when it was expected to.

But the effectiveness of national volcano-monitoring agencies can vary depending on the level of resources and expertise.

New Zealand is one of the world leaders in this field and assists developing countries such as Pacific island Vanuatu in predicting eruptions. Its most active volcano erupted in December.

The technology it uses to monitor volcanic activity includes GPS (global positioning system) receivers, high-tech sensors and drones, as well as dispatched teams on the ground.

Ben Kennedy, a volcanologist at Canterbury University in New Zealand, says they are "getting better all the time" at making predictions.

"If you compare with earthquakes, we are much better at predicting volcanic eruptions than large tectonic earthquakes," he says.