Yeonpyeong: Tiny South Korean island watching the horizon

- Published

On a clear day you can see Haeju city in North Korea with the naked eye

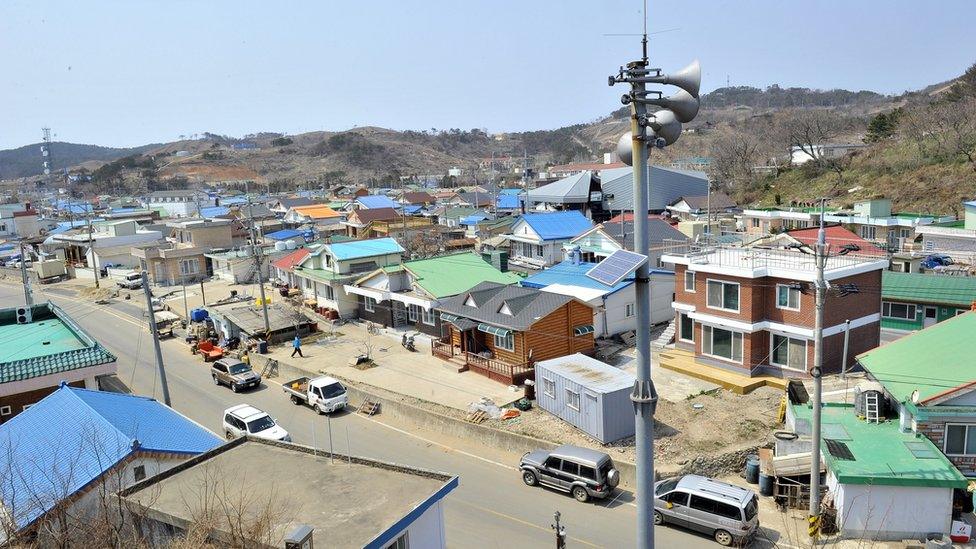

Two-and-a-half hours by ferry from Incheon, South Korea, is the small island of Yeonpyeong.

It looks from the ferry like any South Korean island, until you notice the heavy military presence. It seems like everyone here is wearing camouflage - even the fishermen.

That's because the island is only 40km (25 miles) away from Haeju, North Korea. On a clear day, you can see shoreline with the naked eye. And only 4km away is a tiny North Korean island stocked with rocket artillery launchers.

As tensions rise yet again on the Korean peninsula, people on Yeonpyeong have good reason to be nervously watching the horizon.

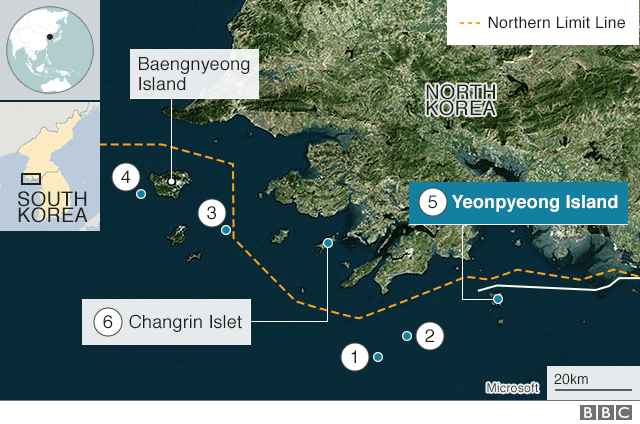

Disputed line at sea

"When I came to my senses after we evacuated I looked over what I had actually brought with me," said Ms Kang, a Yeonpyeong resident.

"I realised I'd only brought the winter jacket I was wearing and two pairs of socks for my babies."

Soldiers stationed at a Yeonpyeong watchtower

Ms Kang - she didn't want to give her full name - was among hundreds of people hurriedly evacuated from Yeonpyeong in 2010 after North Korea carried out what remains its only deadly attack on South Korean soil since the war.

Tensions had been building for some time as North Korea grew in confidence and strength.

The Korean War ended in 1953 with an armistice which set up clear borders on land - the Military Demarcation Line and the Demilitarized Zone. But neither side could agree on what to do with the sea.

Later that year, amid concerns South Korean leader Syngman Rhee, who opposed the deal, might attempt an attack on the North by sea, the US imposed the North Limit Line (NLL), to keep the two sides apart.

Five islands, including Yeonpyeong, lay on the southern side.

North Korea was not happy about the NLL - not least as it cut off access to important fishing grounds - but with its weaker naval force it had no choice but to tolerate it. Then after two decades it began to start pushing back, eventually declaring its own more generous sea boundaries.

North Korean Navy ships began to cross the NLL on purpose, and from time to time attacked South Korean vessels. Then in 1999 and again in 2002 deadly clashes broke out between the two naval forces west of Yeonpyeong Island. Another deadly clash followed in 2009 near Daechong Island.

In March 2010, the South Korean warship the Cheonan sank near Yeonpyeong, killing all 46 on board and shocking South Korea. An official international investigation concluded that the warship had been sunk by a North Korean torpedo attack, something the North has always denied.

Then on the morning of 23 November 2010, South Korea carried out routine drills on Yeonpyeong, despite objections from the North.

North Korea was furious, claiming live shells had fallen into waters it claimed. Hours later, it fired dozens of artillery shells towards the island. Two soldiers and two civilians were killed.

It remains the only time North Korea has deliberately attacked and killed South Koreans on South Korean soil since the war.

The bombardment of Yeonpyeong is the only time North Korea has deliberately attacked civilian territory since the Korean War

With fires breaking out, buildings damaged and power shortages, the government ordered the roughly 1,000 residents to evacuate for the mainland. They would stay away from their island home for three months, living with relatives or in motels. Some even stayed in a public bathhouse.

'Matter of national security'

Once the immediate danger passed, the question arose of whether it was safe to go back to Yeonpyeong.

Many didn't want to.

Aside from safety, the island's economy had never recovered from the collapse of the yellow croaker fishing industry in the 1960s, the result of overfishing and climate change. Many people had left for the mainland even before the shelling.

The evacuees asked for the government's support to help them relocate permanently, but the government disagreed.

The vice-minister of the interior and safety, Ahn Yang-ho, said in a committee meeting that it was a matter of national security.

"If all the residents leave and only soldiers remain in the island, this could lead to the zone becoming an international conflict area in many ways. Considering our national security policy to defend the NLL at any cost, we think we shouldn't support the residents to leave the island," he said.

People like Ms Kang couldn't afford to move themselves, unless they could sell their homes.

"But who's going to buy a house in Yeonpyeong after that?" she said.

A few thousand people still call Yeonpyeong home

These days, Yeonpyeong has about 2,000 residents. The defence ministry won't disclose the actual number of military personnel there, but villagers say a little under half of the registered dwellers are related to the military.

Many others rely on part-time jobs subsidised by the government, designed to encourage the population to remain.

Mrs Kim, a woman in her 50s who also asked to be not named, moved to the island two years after the bombardment when her husband took up one of these jobs.

"If I had experienced it [the bombardment] myself, I wouldn't have come here to live." she said.

"To be frank, I'd like to leave this place as soon as the [subsidised] job ends."

There's a daily ferry to the mainland, but it's unreliable because of changing tides. Islanders have been asking for a new port which would allow larger vessels to dock regardless of the tide in case of emergency. There was a plan for one, but the budget was cut.

"I'm so afraid... there will be no ship for us [to evacuate] when something happens."

Relations between North and South Korea seemed to be on track for a period of time

In 2018, South Korea's President Moon Jae-in and North Korea's Kim Jong-un signed the historic Panmunjom Declaration, announcing a new era of peace on the Korean peninsula and their commitment to formally end the Korean War.

Among the agreements was that both sides would "cease all live-fire and maritime manoeuvre exercises" around the Northern Limit Line, and cover up their artillery and ship guns in the area.

"By making the Korean peninsula into a permanent peace zone, now we can put back our lives into normal," said Mr Moon.

But the optimism of early 2018 has faded, as Kim Jong-un's talks with US President Donald Trump collapsed when North Korea refused to give up its nuclear weapons before the US made some major concessions on sanctions.

North Korea has given the US until the end of this year to come up with a new deal. And as the deadline approaches, Pyongyang has been ratcheting up the tension again.

On 25 November, North Korean state media reported that a coastal artillery company in the Changrin Islet had held a live-fire drill under the guidance of Kim Jong-un. South Korea's defence ministry condemned this as a violation of the agreement.

Two days later, a North Korean civilian vessel crossed the NLL and roamed around what South Korea considers to be its territorial waters for almost 20 hours. Only after the South Korean Navy fired warning shots did it go back beyond the line.

Then last week, North Korea conducted a "crucial test" in a satellite launch station it had once promised to dismantle.

South Korea has also conducted drills.

The evening I arrived on the island, red beams of light could clearly be seen flying out of a Marine Corps unit to the sky, accompanied by the droning sound of the Vulcan anti-aircraft cannon. Villagers said the Marine Corps had notified them of further live-fire drills tomorrow involving mortars and the Vulcans.

One islander said the bombardment happened "out of the blue"

It's got islanders concerned.

"We agreed to stop the drills, didn't we?" Park Tae-won, 59, tells me.

"But we're doing it now. Whatever it is… be it mortars or Vulcans. We shouldn't do that here."

The Marine Corps unit told me that drills involving small-calibre weapons did not violate the agreement. But North Korea has since condemned it as "warmongers' military provocation".

Mr Park, a native islander who's been making a living by fishing for more than three decades, remembers the day of the bombardment.

"When I take a look back to the past when the bombardment and the battles [of Yeonpyeong] happened, there always had been signs," he said.

"After the signs, it just happens out of the blue. Away from where we expected. There was an artillery fire drill in the Changrin Islet and a few days later a North Korean ship crossed the line [NLL] again.

"This makes me very anxious. It makes me think that they could make some problem again at any moment."

- Published25 November 2010

- Published28 March 2011

- Published21 April 2020

- Published5 December 2019

- Published5 September 2023