Parasite: The real people living in Seoul's basement apartments

- Published

A surprise box office hit telling the story of a poor South Korean family living in a tiny, dark semi-basement, and a wealthy family living in a glamorous home in Seoul.

But while the Oscar-winning film Parasite is a work of fiction, the apartment is not. They're called banjiha, and thousands of people live in them in South Korea's capital, Seoul.

Julie Yoon, of BBC Korean, went to meet some of them, to find out what life is like there.

There's basically no sunlight in Oh kee-cheol's banjiha.

It gets so little light that even his little succulent plant couldn't survive.

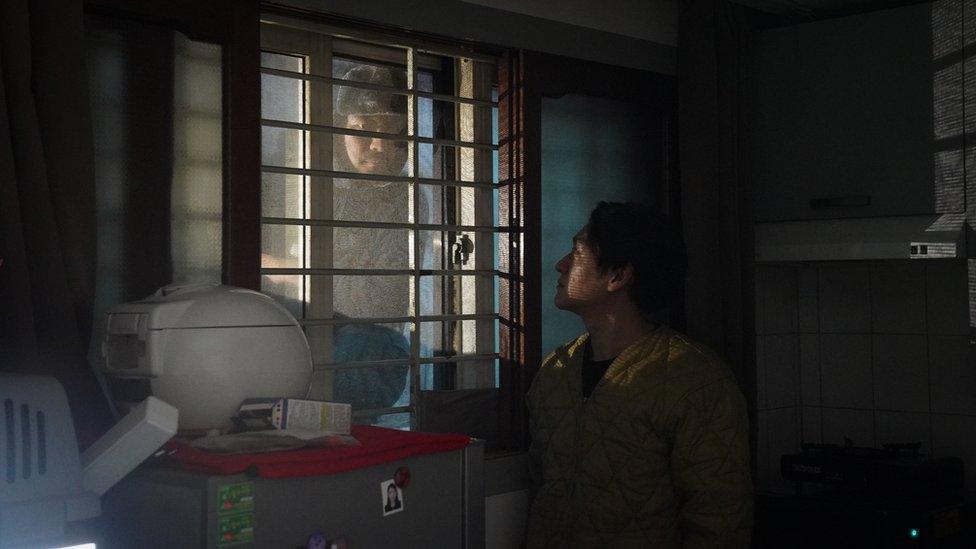

The street offers a direct view into Oh kee-cheol's apartment

People can peer into his apartment through the windows. Teenagers occasionally smoke outside his flat, or spit onto the ground.

In the summer, he suffers from unbearable humidity and battles with rapidly growing mould.

The tiny bathroom has no sink and is raised half a metre above the floor. The ceiling of the bathroom is so low he has to stand with his legs wide, to avoid banging his head.

"When I first moved in, I got bruises from banging my shin on the step and scrapes from stretching my arms against the concrete walls," says Oh, 31, who works in the logistics industry.

Oh kee-cheol can't stand completely upright in his bathroom because of the raised floor

But now he says he's used to it.

"I know where all the bumps and lights are."

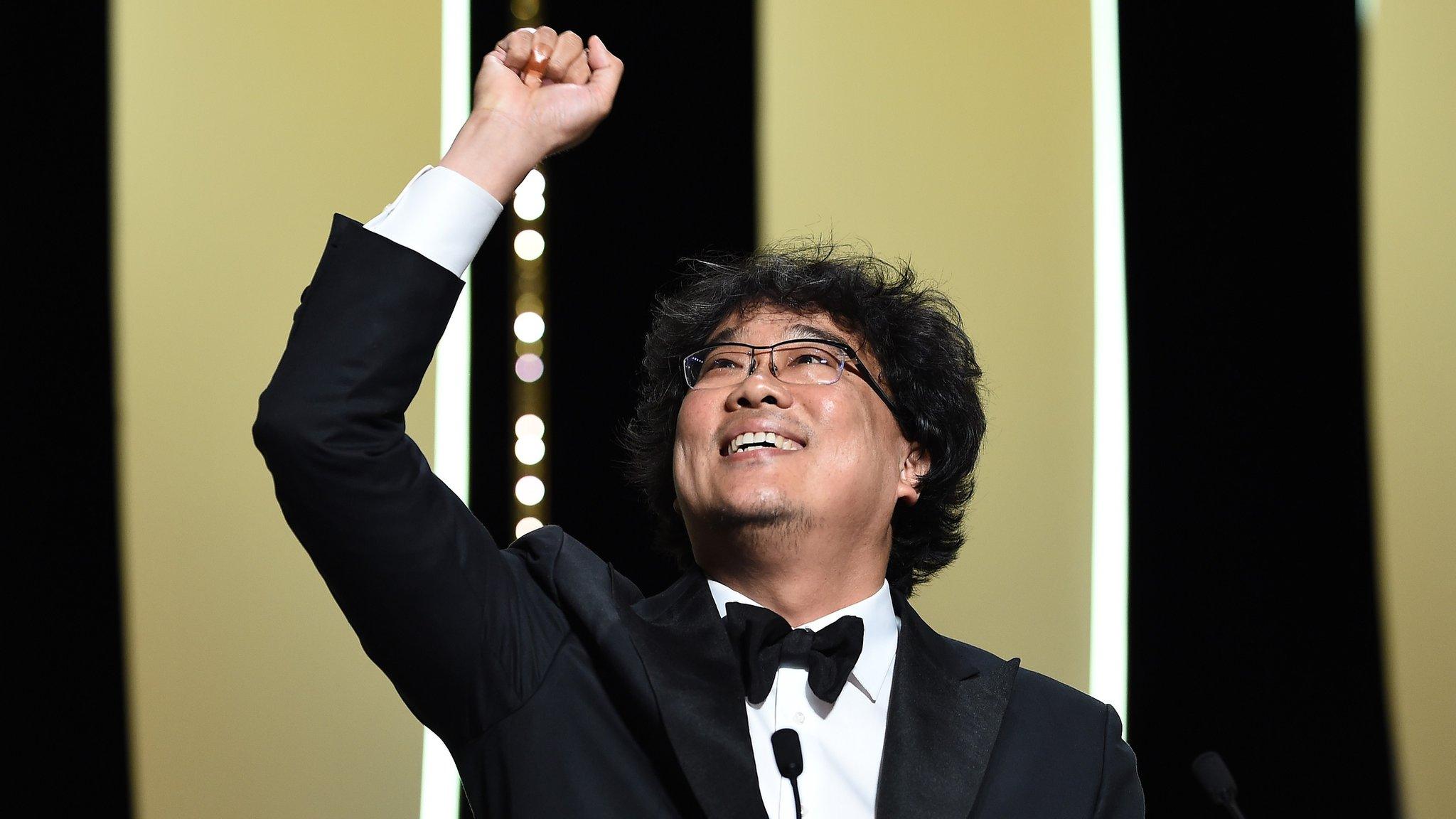

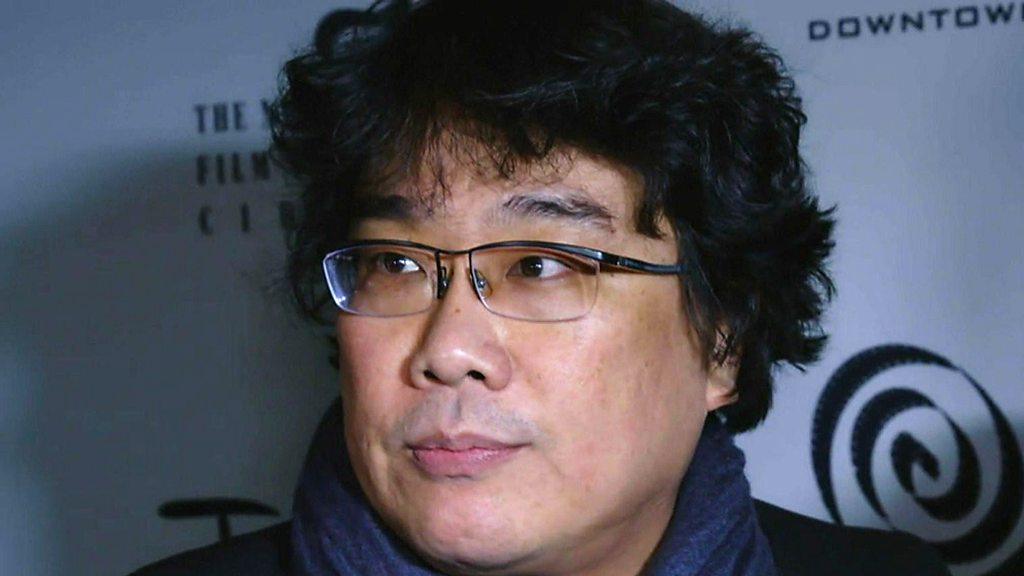

Parasite, the stealth hit by legendary director Bong Joon-ho, is a twisted tale of the haves and have-nots.

The extreme disparity between the two families - the affluent Parks and the poor Kims - is shown through their two homes. One a gleaming mansion up on the hills above Seoul; the other a dingy semi-basement.

In real-life Seoul, though, banjihas are where thousands of young people end up living, while they work hard and hope for a better future.

The Kims' bathroom in Parasite (left) is an accurate representation of how Oh lives (right)

The Parks' home in the film is in contrast bright, spacious and luxurious

The banjihas are not just a quirk of Seoul architecture, but a product of history. These tiny spaces actually trace their roots back decades, to the conflict between North and South Korea.

In 1968, North Korean commandos slipped into Seoul on a mission to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee.

The raid was thwarted, but the tension between the two Koreas intensified. That same year, North Korea also attacked and captured a US Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo.

Armed North Korean agents infiltrated South Korea, and there were a number of terrorist incidents.

Fearing an escalation, in 1970 the South Korean government updated its building codes, requiring all newly built low-rise apartment buildings to have basements to serve as bunkers in case of a national emergency.

Initially, renting out such banjiha spaces was illegal. But during the housing crisis in the 1980s, with space running short in the capital, the government was compelled to legalise these underground spaces to live in.

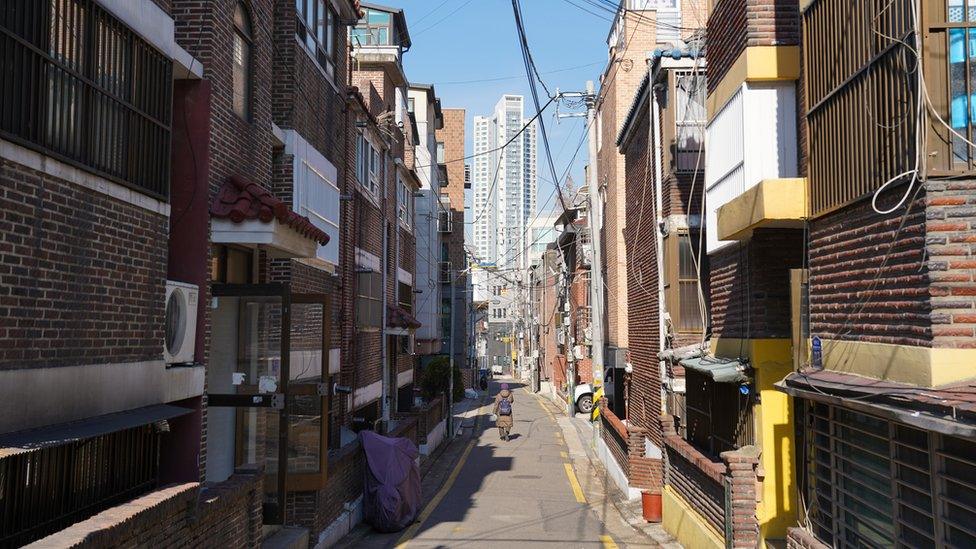

In crowded Seoul, space is at a premium and rents are high

In 2018, the UN noted that despite having the world's 11th largest economy, South Korea's lack of affordable housing was a substantial barrier - particularly for young people and poorer people.

For under-35s, the rent-to-income ratio has remained at around 50% during the last decade.

So the semi-basement apartments have become an affordable response to rapidly-growing housing prices. Monthly rents are around 540,000 Korean won (£345; $453), with average monthly salaries for people in the 20s around 2m won (£1,279; $1,679).

Nevertheless, some banjiha dwellers struggle to overcome the social stigma. But not all.

Oh kee-cheol says he has grown to like his semi-underground home

"You know, I'm genuinely OK with my apartment," says Oh.

"I chose this place to save money and I'm saving a lot from it. But I've noticed I can't stop people pitying me.

"In Korea, people think it's important to own a nice car or a house. I think banjiha symbolises poverty.

"Perhaps that's why where I live defines who I am."

Midway through Parasite, as the poor Kim family infiltrate the lives of the Parks to try to make money off them, the youngest Park, Da-song notices a smell among the Kim family.

When Kim Ki-taek, the father, tries to get rid of the smell, his daughter says coldly: "It's the basement smell. The smell won't go away unless we leave this place."

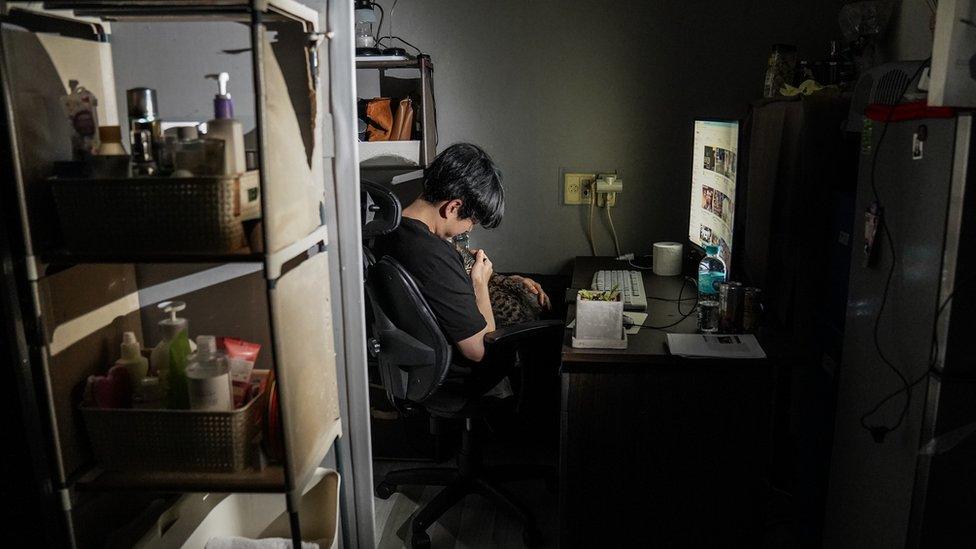

Park Young-jun (right) was attracted to the space and low rent of the banjiha

Park Young-jun, a 26-year-old photographer, watched Parasite soon after he moved into his banjiha apartment. Initially, Park's reason for choosing a banjiha was straightforward: affordability and space.

However, he couldn't help but feel conscious about the smell after watching the movie. "I didn't want to smell like the Kim family," he says.

That summer, he burnt countless incense sticks and kept his dehumidifier on most of the time. In some ways, he says the film motivated him to fix up his flat and decorate it.

"I didn't want people to feel sorry for me just because I live somewhat underground," he explains.

Park and his girlfriend, Shim Min, kept a vlog about their banjiha apartment makeover.

They are very happy with the place, but it took months to get where they are now.

Park Young-jun and Shim Min have renovated the apartment together

"When my parents saw the apartment for the first time, they were in dismay. The previous tenant was a heavy smoker and my mom couldn't get over the smell," says Park.

Shim, a 24-year-old YouTuber, first strongly disagreed with Park when he made a decision to live in banjiha apartment.

"I had a very negative perception of banjiha. It didn't look safe. It reminded me of the dark side of the city. I grew up in high-rise apartment complexes all my life, so I was worried about my boyfriend."

But their home makeover videos have had positive feedback from their subscribers. Some even envy how stylish their flat is.

"We love our home and are proud of the work we've done here," says Min. But she points out that it doesn't mean that they want to settle in banjiha forever. "We are going to move up."

Oh is also saving up to buy his own place. By living in semi-basement, he hopes to realise his dream much sooner.

"My only regret is that my cat, April, can't enjoy the sun through the window."

All images Julie Yoon

- Published30 January 2020

- Published10 February 2020

- Published13 January 2020

- Published10 February 2020

- Published25 May 2019