Coronavirus privacy: Are South Korea's alerts too revealing?

- Published

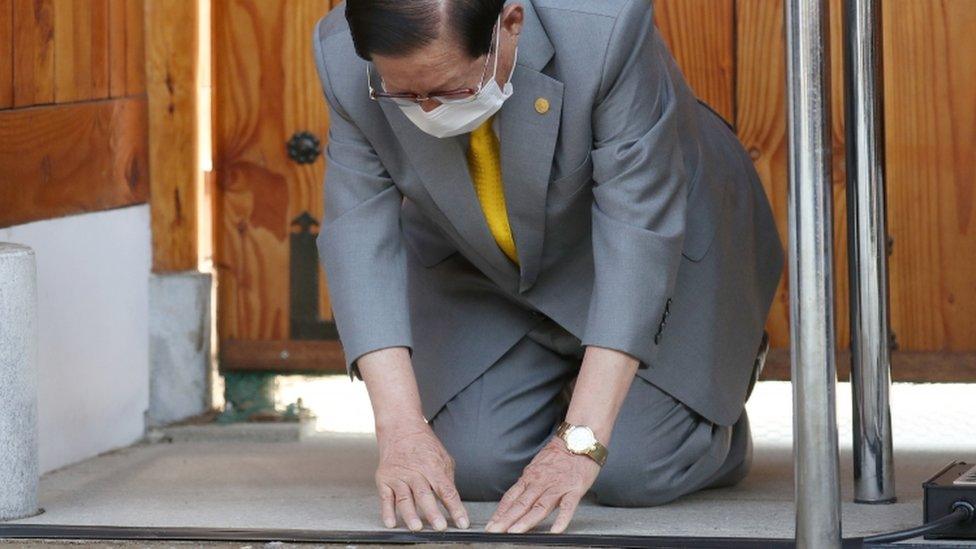

As South Korea battles a snowballing number of Covid-19 cases, the government is letting people know if they were in the vicinity of a patient. But the volume of information has led to some awkward moments and now there is as much fear of social stigma as of illness, as Hyung Eun Kim of BBC News Korean reports.

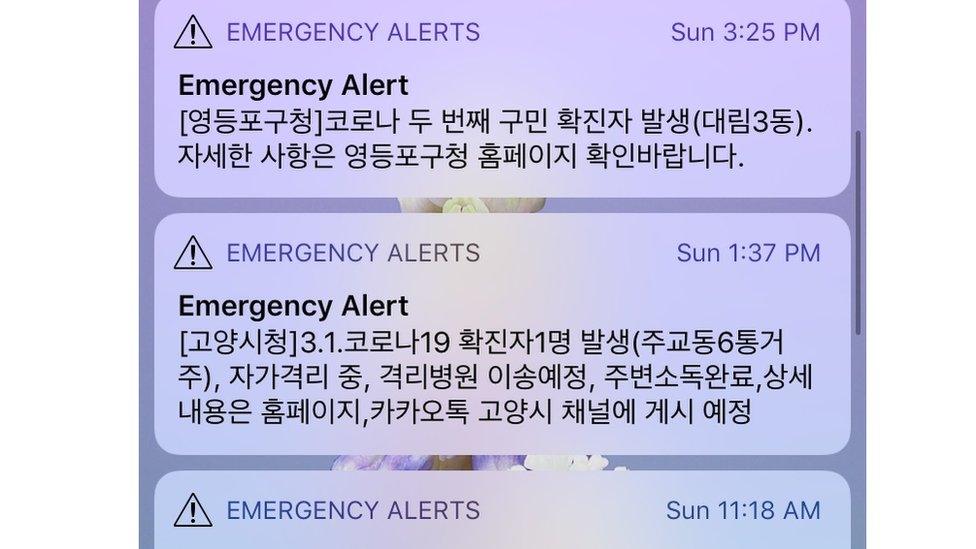

As I sit at home, my phone beeps alarmingly with emergency alerts.

"A 43-year-old man, resident of Nowon district, tested positive for coronavirus," it says.

"He was at his work in Mapo district attending a sexual harassment class. He contracted the virus from the instructor of the class."

A series of alerts then chronicle where the men had been, including a bar in the area until 11:03 at night.

These alerts arrive all day, every day, telling you where an infected person has been - and when. You can also look up the information on the Ministry of Health and Welfare website.

No names or addresses are given, but some people are still managing to connect the dots and identify people. The public has even decided two of the infected were having an affair.

And, even if patients are not outright identified, they're facing judgement - or ridicule - online.

Examples of the messages Koreans get, alerting them to new cases

When you search online for a virus patient's case number, related queries include "personal details", "face", "photo", "family" - or even "adultery".

Some online users are commenting that "I had no idea so many people go to love motels" - the by-the-hour hotels popular with couples.

They are also joking that people cheating on their spouses are known to be keeping a low profile these days.

One recent alert concerned a woman, aged 27, who works at the Samsung plant in Gumi. It said that at 11:30 at night on 18 February she visited her friend, who had attended the gathering of religious sect Shincheonji, the single biggest source of infections in the country.

City mayor Jang Se-yong further revealed her surname on Facebook. Panicked Gumi residents commented on his post: "Tell us the name of her apartment building."

"Please do not spread my personal information," the woman later wrote on Facebook.

"I am so sorry for my family and friends who would get hurt, and it's too hard for me psychologically, more than (physical pain)."

"We're often persecuted": Spokesman for virus-hit S Korean church defends secrecy

South Korean laws on managing and publicly sharing information on patients of infectious diseases changed significantly after the Mers outbreak in 2015.

South Korea had the second-largest number of Mers cases after Saudi Arabia. At the time, the government was criticised for withholding information, such as where the patients had been.

After that, the laws were amended to empower investigators.

"We know that it is [in the] the territory of important personal data," Goh Jae-young, an official at the Korea Centers for Disease Control Prevention, told BBC Korean.

"At first we interview the patients and try to gather information, emphasising that this affects the health and safety of the entire people.

"Then to fill in the areas they perhaps haven't told us, and also to verify, we use GPS data, surveillance camera footage, and credit card transactions to recreate their route a day before their symptoms showed."

Mr Goh emphasises that they do not reveal every place a patient has been.

"We share with the public only places where there was close contact or infections could have spread - like where there are many people, where the patient was known to have not worn a mask."

Sometimes they have to reveal the name of specific store, too - which leads to closure for certain time and financial loss to the business owner.

South Korea has had more than 5,000 confirmed case of Covid-19 and more than 30 deaths.

But with most cases not leading to serious health problems, South Koreans now dread stigma as much as they fear the virus itself.

A research team at Seoul National University's Graduate School of Public Health recently asked 1,000 Koreans which scares them the most:

Potential carriers around them

Criticisms and further damage they may suffer from being infected

That they may not have symptoms yet have the virus

Prof You Myoung-soon's team found "criticisms and further damage" were more feared than having the virus.

A man who contracted the virus along with his mother, wife and two children wrote an emotional, lengthy post on Facebook asking people to stop blaming them.

"I didn't know my mother was a follower of Shincheonji [church]," he wrote. He went on to defend his wife, a nurse, who had been criticised for visiting so many places during her incubation period.

The husband said her job was to accompany people with physical disabilities to clinics for appointments, and she had no idea she had the virus.

"It is true my wife moved around a lot, but please stop cursing her. Her only fault is marrying someone like me, and having to work and take care of the children."

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

LATEST: Live coverage of developments

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Doctors warn that online pursuit of patients could have very serious consequences. Malicious comments online have long been a problem in South Korea, and in some cases have led to suicide.

Lee Su-young, a psychiatrist at Myongji Hospital in Goyang, Gyeonggi, told BBC Korean that some of her patients "were more afraid of being blamed than dying of the virus".

"Many have told me repeatedly 'someone I know got infected because of me,' [or] 'the person is quarantined because of me.'"

It was at Myongji Hospital that the two people accused of being in adulterous relationship were treated. One is known to have high levels of anxiety and suffered sleep deprivation due to online comments.

As the virus spreads rapidly, it's vital that the public are giving the information they need to protect themselves and others.

But Dr Lee says the public needs to remain mature with this information - otherwise "people who fear being judged will hide and this will put everyone in further danger".

Mr Goh, from the Korea Centers for Disease Control Prevention says this is the first time the government has given quite so much information about each individual affected.

''After the spread of virus ends," he says, "there has to be society's assessment whether or not this was effective and appropriate."

The BBC's Health team talks you through what the NHS says about protecting yourself from Covid-19

- Published2 March 2020

- Published2 March 2020