Coronavirus: I watched the president reveal I had Covid-19 on TV

- Published

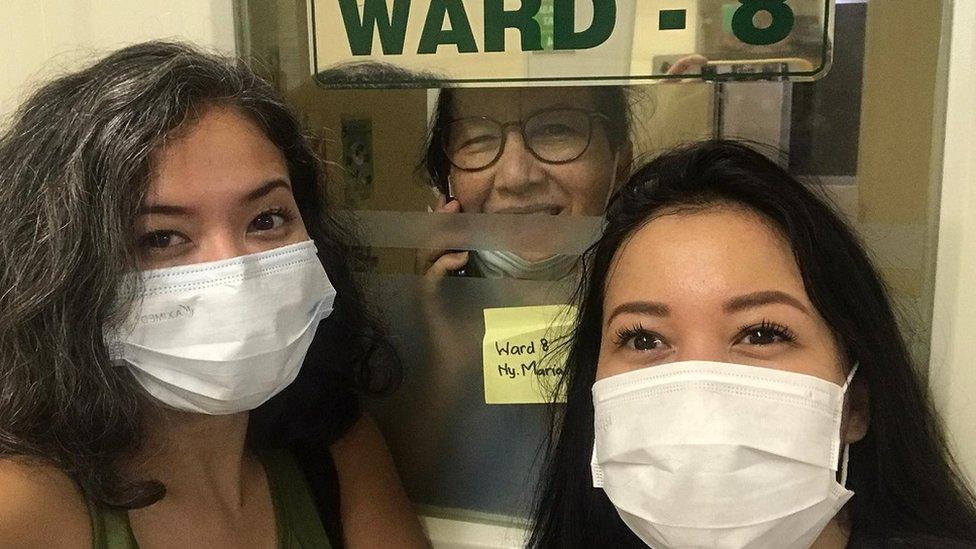

Sita Tyasutami (L), Maria Darmaningsih (C) and Ratri Anindyajati (R) said Covid-19 has changed their lives forever

A high fever, nausea and a dreaded dry cough.

Sita Tyasutami had all the tell-tale symptoms of coronavirus. Yet, as she lay in a hospital bed in Indonesia's capital Jakarta, her condition had not been diagnosed. Nor had that of her mother, Maria Darmaningsih, who had been admitted to the same hospital.

Confined to separate hospital rooms, Tyasutami and her mother were anxiously awaiting the results of their coronavirus tests, when Indonesia's president made a startling announcement.

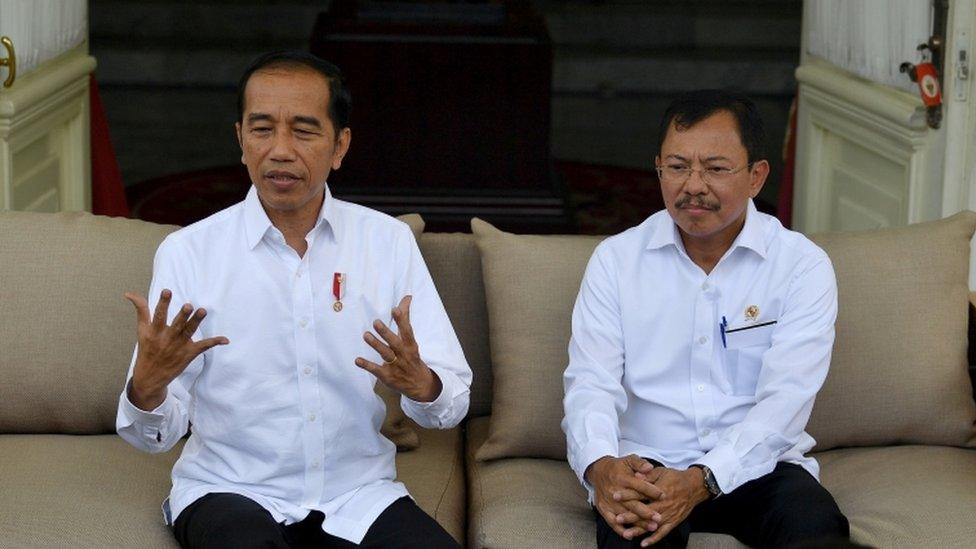

In a news conference broadcast to the nation, President Joko Widodo said two Indonesian nationals had tested positive for Covid-19, the first two confirmed cases in the country. The pair - a 64-year-old woman and her 31-year-old daughter - were being treated at an infectious diseases hospital in Jakarta, the president said.

The briefing, held in front of jockeying reporters outside the presidential palace, confirmed the inevitable: coronavirus had reached Indonesia.

Aired on TV screens at the hospital, the president's announcement left Tyasutami and her mother in disbelief. President Widodo was talking about two patients at their hospital, with their profiles, their ages, their symptoms, their contact history.

President Widodo did not mention the patients by name, but he did not have to.

Her brain whirring, Tyasutami asked a nurse whether the hospital was currently treating any other coronavirus patients. When the nurse said no, reality hit her like a punch to the gut.

She and her mother had been revealed as the first two known cases of coronavirus in Indonesia. "I was confused, I was angry, I was sad," Tyasutami told the BBC. "I didn't know what to do because it was all over the media."

Before her diagnosis, Tyasutami was a professional dancer, a performing arts manager, a sister, a daughter, a friend. Afterwards, her identity was reduced to a humiliating two-word label: case one. Her medical records were leaked. The details of her case were misreported. False rumours spread online.

Within a matter of hours, she became the face of Indonesia's coronavirus outbreak.

It started with an itchy throat.

Tyasutami brushed it off. It was nothing to worry about, she thought. Then, on the morning of 17 February, she woke up with symptoms that were more than just the hallmarks of a benign illness.

Her mother Darmaningsih, a professor of dance at the Jakarta Institute of Arts (JIA), fell ill later that week. Darmaningsih's condition worsened after a dance performance on 23 February, leaving her feeling "very sick".

At this point, Darmaningsih and Tyasutami went for a medical check-up at their local hospital in Depok, on the outskirts of Jakarta. Initially, the doctor diagnosed Darmaningsih with typhus - a bacterial disease spread by lice or fleas - and Tyasutami with bronchopneumonia.

"We asked to be tested for Covid-19, but our request was rejected because, at the time, the hospital didn't have the right facilities," Tyasutami said.

Tyasutami said the first hospital she attended did not have Covid-19 testing facilities

On 27 February, they were kept in hospital, unaware of the pathogen invading their cells. It took a tip-off from a friend, 24 hours later, to set alarm bells ringing. The friend phoned Tyasutami to tell her she had attended the same dance event as a Japanese woman who had tested positive for Covid-19.

Tyasutami did not know the Japanese woman, but understood the gravity of her diagnosis.

"That's why I insisted once again to the doctor to be tested," Tyasutami said.

Doctors yielded to her request this time. She and her mother were transferred to Sulianti Saroso, Jakarta's infectious disease hospital, where they underwent a swab test for Covid-19.

Tyasutami and her mum were transferred to an infectious disease hospital in Jakarta

Tyasutami and Darmaningsih expected a doctor to tell them the results. Instead, their diagnoses were read out by President Widodo on 2 March. It was as much of a surprise to them as it was to the country. A few days would pass before Tyasutami and Darmaningsih were told that, in the event of a disease outbreak, the president must be informed before patients, by law.

Achmad Yurianto, a spokesman for the Indonesian government, told the BBC there was nothing wrong with the president's disclosure to the public. A 2009 health law says patient discretion does not apply to matters of public interest. Therefore, the president's announcement was lawful, according to Jakarta-based legal expert, Bivitri Susanti. Was it the right thing to do, though, given the legal protection of medical records? "I don't think so," Ms Susanti said.

President Widodo announced Tyasutami's diagnosis in a news conference at the presidential palace

Right or wrong, the announcement thrust case one and case two into the national limelight. Within hours, messages showing the initials, full address and medical records of case one (Tyasutami) and case two (Darmaningsih) were leaked and shared widely on WhatsApp. The backlash on social media, and the spread of misinformation about their lives, was immediate, vicious and unrelenting.

"They attacked Sita, blaming her for bringing the virus to Indonesia," Tyasutami's older sister, Ratri Anindyajati told the BBC. "They blamed her for losing their job, or being separated from their families. They questioned how she could look so nice and beautiful after being sick. They said it was a set-up."

Tyasutami is a professional dancer and performing arts manager

Tyasutami was put on trial by the public, even though it was entirely possible Indonesia had coronavirus cases before 2 March. The government had denied there were. But in early February, a study by Harvard University suggested there could be "undetected cases" in the country, external, which has close links to China, where the virus originated.

Now, Indonesia is one of the worst-hit countries in south-east Asia, with about 12,000 cases and almost 900 deaths to date. The origins of Covid-19 in Indonesia may never be known. Case one and two, however, were on record.

"Before my diagnosis, I had less than 2,000 followers on Instagram," Tyasutami said. "I didn't have anyone sending me hate speech. Within days [of my diagnosis], my followers went up to 10,000. People were commenting on everything, especially pictures of me in sexy, revealing dance clothes."

Why "patient zero" is not a helpful term

Analysis by Richard McKay, historian of epidemics and researcher at the University of Cambridge

Given its accidental formation and lack of precision, "patient zero" is always a misleading phrase, so it is best avoided. It was coined by mistake in the 1980s. It is thought by some to mean the first (or "primary") case in a given area by date of infection, by others to mean the first case noticed in an outbreak ("index case"), and by still others to mean the first case "ever" appearing in humans.

The term also has a long history of being used as a sensational, attention-grabbing device and of generating stigma. Real-world conditions - like infected individuals who don't display symptoms - remind us that placing overdue emphasis on any definitive ordering and numbering of cases would be misguided.

If Covid-19 had previously been perceived as a risk far removed from Indonesia, there might be some public education value to confirming the existence of cases in the country. However, whenever the number of cases is small, extreme discretion must be used when discussing them.

On 3 March, President Widodo urged hospital and government officials to respect the privacy of Covid-19 patients, but by that point, the damage was already done.

The leak set the tone for what was to come next. Imprecise comments from Indonesia's health minister, Terawan Agus Putranto, would prove even more chastening. At a news conference on 2 March, the minister wrongly suggested case one (Tyasutami) contracted the disease from a Japanese citizen, external, a "close friend", while dancing at a nightclub in Jakarta. The minister's comments allowed imaginations to run wild.

Tyasutami said she was at the same dance event as a Japanese woman who later tested positive for Covid-19

There were false reports that suggested "the Japanese person was a close friend who was 'renting me'," Tyasutami said. "My story has been twisted so many times. People were making assumptions about me," she added.

The health minister did not respond to requests for comment.

Tyasutami said the media should also take responsibility for the way her diagnosis was reported. "There is this culture of victim blaming," she said. One press freedom group, the Alliance of Independent Journalists, urged the media to avoid "sensationalist" reporting and respect the privacy of Covid-19 patients. The media went too far, Tyasutami felt. While watching television in hospital she could see reporters "bombarding" her house.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

ON FRONTLINE: The young doctors being asked to play god

INSIDE STORY: Spain's care home tragedy

REASON TO HOPE: The good that may come out of this crisis

Everyone at her home had to be tested for Covid-19, including her older sister, Anindyajati. The 33-year-old artist manager, who lives in Vienna, had already been ill and recovered after arriving in Indonesia for a holiday in early February. The test confirmed what Anindyajati had already suspected. She would join her family in isolation at the same hospital, now known as Indonesia's case three.

Anindyajati said she mistook her illness for jet lag at first

Aside from a few complications, the recovery period went fairly smoothly for the three of them.

On 13 March, after 13 days in isolation, Anindyajati and Tyasutami were discharged from hospital. It was a joyous moment tinged with sadness, as their mother - yet to fully recuperate - had to remain in hospital for a further three days. She was not lonely, though, as her daughters kept her company, albeit at a distance.

Anindyajati and Tyasutami kept their mother company in hospital

The experience, they said, has changed their lives forever. "I feel that I have a second chance at life," Darmaningsih said.

They have been supporting families who have not been so fortunate, offering advice when it is requested. They have even donated their blood to researchers trialling a possible treatment for Covid-19.

Now the outbreak has become more widespread, they are just three of thousands of lives turned upside down by the disease in Indonesia. Yet the stigma persists.

Someone called them "Satanic women" in a message a few days ago, Tyasutami said. Anindyajati tries to ignore the hate, instead focusing on the silver lining.

"We believe there were already many suspected cases," she said. "When our diagnosis was confirmed, at least it helped the government to take action."

Additional reporting by Resty Woro Yuniar of BBC Indonesia

You may also be interested in:

Jex Wang said she was sent racist abuse after writing about the coronavirus

- Published13 April 2020

- Published4 April 2020

- Published26 April 2020