Coronavirus in Singapore: Election campaigning without the handshakes

- Published

The coronavirus has ended the handshake

For some politicians, campaigning season is one of the few times they have to get up close and personal with the public, as they try to persuade people to vote them into office.

But the global pandemic has turned everything on its head, national elections included.

Political rallies held online, socially distanced door-knocking sessions, and fist bumps instead of handshakes would have been unthinkable a few months ago, yet this is what politicians in Singapore are having to contend with as the country gears up for its general election on 10 July.

The election next Friday takes place as Singapore records more than 44,000 cases of the coronavirus, most of which stem from outbreaks in dormitories housing migrant manual labourers.

A partial lockdown was eased earlier this month, but social distancing rules are still in place - people are called to stay at least 1m apart and mass gatherings have been banned.

So how do you campaign amid a pandemic?

Let's (not) rally together

Rallies are the lifeblood of election campaigns - they're one of the main ways candidates are able to get their message out to the masses.

The Progress Singapore Party (PSP), which was founded last year, is among 12 opposition parties hoping to make gains this year.

It's a tall order to take on the People's Action Party (PAP), which has ruled Singapore since independence in 1965.

One PSP member said the decision not to hold physical rallies this year would greatly hurt its chances, and said calling an election in the midst of a pandemic was "being done at risk to people".

"The opposition rallies were always a very strong selling point. They are very well attended and there's lots of atmosphere that gets generated in it," Lee Hsien Yang told the BBC during a walkabout.

"To run this election and to forbid any rallies to be held, disadvantages the opposition," said Mr Lee, who happens to be the brother of Lee Hsien Loong, Singapore's prime minister and head of the PAP.

In 2015, one opposition rally drew an estimated crowd of 30,000 - a sizeable number in the country of five million.

An MP from the PAP, however, said the fact that the election was so heavily reliant on online platforms and social media would actually help to balance things out.

"[As the incumbent] we've been walking the ground all these years, a lot of our networks are actually through our face-to-face engagement," Senior Minister of State Chee Hong Tat, who is running as a candidate in the upcoming elections, told the BBC.

"[Taking away these physical opportunities] and using social media, I think actually gives the opposition more opportunities to reach voters, so it does level the playing-field on this front."

The PAP has ruled Singapore since its independence

But politics aside, there are a whole other range of difficulties that the lack of physical rallies brings.

"In a physical rally, someone travels from his house to a venue, and once he gets there he typically devotes around an hour of time to listen to what you have to say," said Mr Tan, a PSP member who has been involved in setting up the group's online presence.

"In a physical rally you can plan your speech - you know what your intro will be, your middle and how to end. But in a virtual rally, you're more likely to have 15 seconds to capture someone's interest," he told the BBC.

The tech that goes on behind the scenes of a livestreaming session

And even if you do capture their initial interest - you've got to be able to maintain it.

"You probably have five parties doing an online rally at around the same time - it's like channel surfing. So the challenge is how to engage and connect with the audience," Mr Tan said.

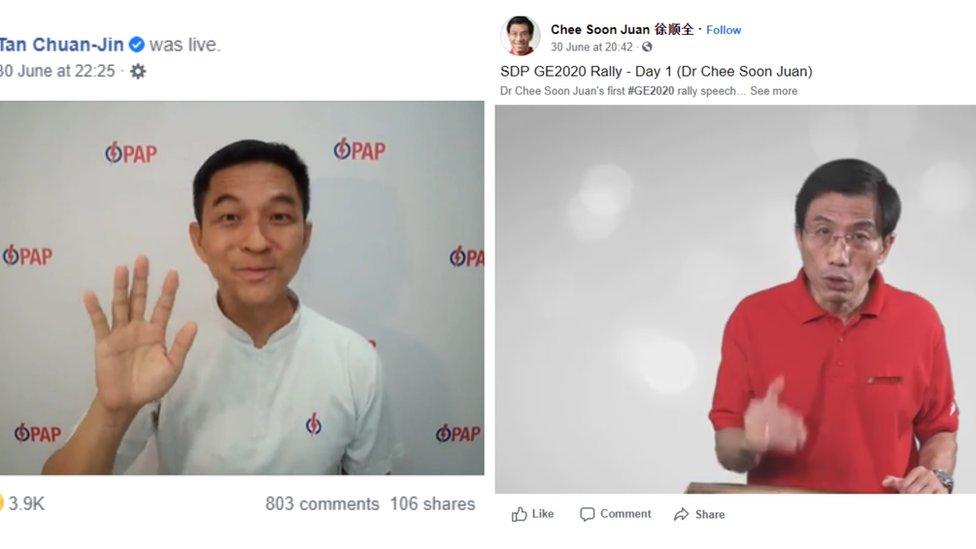

Different candidates have been holding Facebook Lives to reach voters

A mix of new and old

Another hurdle is getting through to groups who might not be used to going online - elderly people who may be less tech-savvy, for example.

"You can produce all the content you want but the difficulty is getting it to reach the correct people. If you're not a politically-inclined person these ads may not pop up on your Facebook," said Mr Tan.

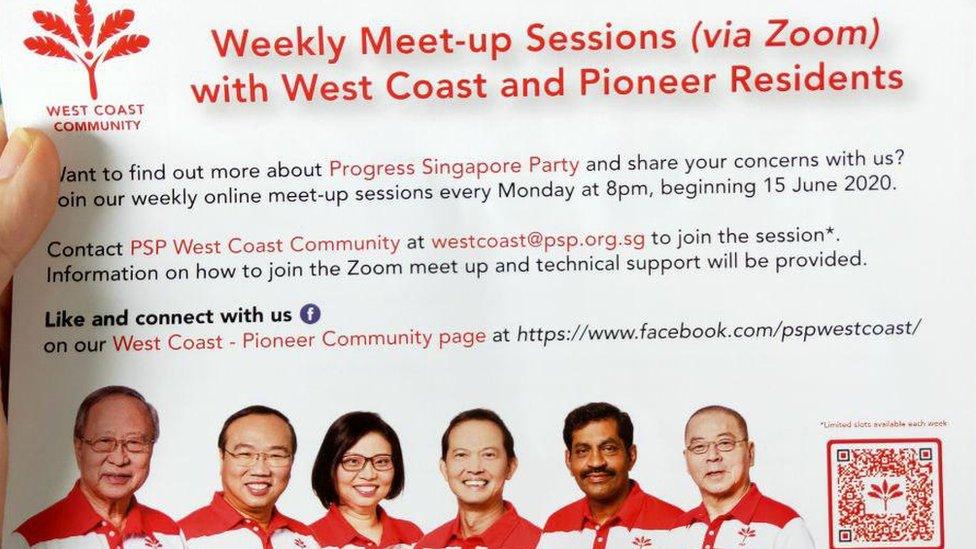

The group's plan to combat this is to print out flyers directing people to their online presence.

The PSP have been handing out flyers for their Zoom sessions

"We distribute flyers directing people to our Facebook page and our meet-up sessions via Zoom," said Mr Tan.

"We did a survey later and found about 60% of people found out about our Zoom session through the flyer. So [it's a] hybrid - mixing the traditional with the modern methods is the way to go."

But that doesn't mean the traditional methods have faded away completely.

Candidates are still walking the ground and knocking on doors, but are having to do so in smaller groups - and at a distance.

The PSP during a door-knocking session

"[On door-knocking visits] we observe social distancing, our team is not more than five people, and we want to keep the interactions with residents quite brief, so we don't have prolonged contact," said PAP candidate Mr Chee.

"[We are still carrying our visits because] online is not a perfect substitute for face-to-face interactions, especially for many of our seniors who may not be familiar with IT."

It's certainly not perfect - but candidates running have little choice but to make the best of their circumstances.

"As a voter, your contact point the candidate is now limited to [a few] seconds. Not being able to shake hands, that's not a big issue, [but rather] the lack of visual recognition," said Mr Tan.

"[When you see someone in a mask] you might not have visual recognition, or you can't remember exactly which candidate it was. This is definitely not the preferred way of [campaigning] - but at the end of the day, safety has to come first."

- Published29 June 2020

- Published10 April 2020

- Published14 June 2020