Coronavirus Vietnam: The mysterious resurgence of Covid-19

- Published

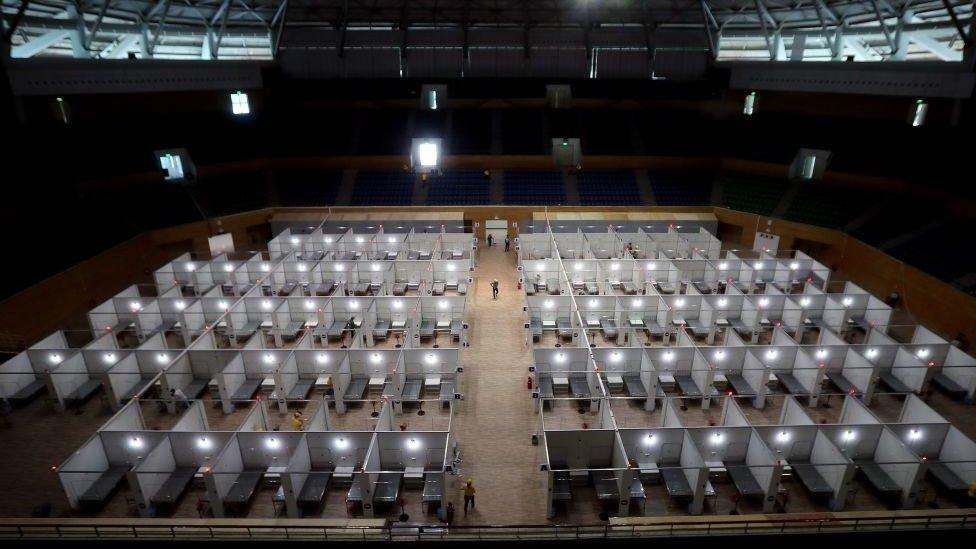

Returnees from Da Nang are tested for Covid-19 in Hanoi

In mid-July, Vietnam still shone as a Covid-19 outlier. No reported deaths, and months without a locally transmitted case.

Fans packed into football stadiums, schools had reopened, and customers returned to their favourite cafes.

"We were already back to normal life," said Mai Xuan Tu, a 27-year-old from Da Nang in central Vietnam.

Like many in the coastal city wildly popular with domestic visitors, she works in the tourism industry and was slowly resuming bookings for the tour company she founded.

But by the end of July, Da Nang was the epicentre of a new coronavirus outbreak, the source of which has stumped scientists. Cases suddenly surged after 99 straight days with no local transmissions.

Last week the city saw the country's first Covid-19 death, a toll that has since risen to 10.

Successful response

Just weeks earlier, Vietnam was praised globally as a rare pandemic success story.

Scottish pilot Stephen Cameron spent 10 weeks in a coma in Vietnam

The communist country acted fast and decisively where other nations faltered, closing its borders to almost all travellers except returning citizens as early as March.

It quarantined and tested anyone who entered the country in government facilities, and conducted widespread contact-tracing and testing nationwide.

So what went wrong?

"I'm not sure anything went wrong," says Prof Michael Toole, an epidemiologist and principal research fellow at the Burnet Institute in Melbourne.

Most countries that thought they had the pandemic under control have seen resurgences, he says, pointing to a long list including Spain, Australia and Hong Kong.

"Like in the first wave, Vietnam has responded quickly and forcefully."

Around 80,000 visitors in Danang - many of whom had relaxed into thinking the disease was contained - were flown home promptly after the new cases emerged, as the historic port city sealed itself off from visitors and retreated into full lockdown.

Vietnam's spike shows that "once there's a little crack and the virus gets in it can just spread so quickly," Prof Toole says.

Scientists and researchers across the country are racing to find out exactly how it did.

In Hanoi Prof Rogier van Doorn, director of the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, says the source of this latest outbreak remains a "big mystery".

His team works with the government on its infectious diseases programmes and some of them focus on what he calls "genetic detective work" - the sequencing of viruses that can help illuminate "the chains of transmission. Who or where the virus came from".

But so far no-one knows how the first new case in Da Nang - a 57-year-old man known as patient 416 - came into contact with the coronavirus.

A family wait to be tested at a makeshift rapid testing centre in Hanoi

The knowledge gap has allowed some speculation to set in.

Local media have carried reports suggesting the latest outbreak may have been caused by a more virulent strain of the virus. Others have pointed to recent people-smuggling cases along the Vietnam-China border.

But there is no evidence to suggest a more deadly strain or that migrants have brought the virus into the country.

National pride

A more likely possibility, say researchers, is that the virus went undetected during the months where there were no reported cases, potentially being asymptomatically transmitted in the community. Or there could have been an error somewhere along the quarantine process with someone released prematurely.

"There's evidence [the virus] was circulating in Da Nang for several weeks before that first case was diagnosed," says Dr Justin Beardsley, a senior lecturer in infectious diseases at the University of Sydney whose research has focused on Vietnam.

There could be some element of people dropping their guard, he adds, while noting that Vietnam showed exceptionally strong community engagement when it came to curbing spread of the virus.

"There was big national pride about controlling the pandemic. And I think that's been missing in some Western countries."

Since hovering around the 400 mark in late July, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in Vietnam has surged above 780. The deputy health minister has said they expect numbers to rise and forecast on Wednesday that the epidemic will reach a peak in 10 days.

With the recent tourists to Da Nang now back at home, cases have been detected in a total of 14 cities and provinces including the capital and Ho Chi Minh City.

But it has been reassuring, says Prof Van Doorn, that all new cases in other parts of the country so far have had a direct link to the Da Nang outbreak. Crucially, there has been no reported community transmission outside of the city and bordering province. This is something authorities will be monitoring closely.

"What was successful before is being done again. I'm again impressed," he adds.

'The year we look after our health'

Speckled among the praise showered on Vietnam for its handling of Covid-19 were some questions about the accuracy of the authoritarian state's data, which medical and diplomatic communities had widely agreed was reliable.

"The new deaths reported shows that there is transparency in reporting Covid-19 in Vietnam and that previous 'no deaths' should have not been questioned in the first place," Dr Huong Le Thu, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, tells the BBC.

All the fatalities so far have been older patients with co-morbidities.

A field hospital has been built inside a sports complex in Da Nang

In Da Nang residents are readjusting. The beaches and streets are virtually empty once again as people only leave home to buy food. All eateries have been closed, including for takeout and deliveries. Flights are grounded.

Each resident is set to be tested for the virus, and a field hospital has been erected as every resource is thrown at slowing the spread of the disease.

Freedoms mostly remain intact in other parts of the country, though Hanoi has closed down bars and karaoke parlours as an extra precaution, and several cities including the capital and Ho Chi Minh City have made face masks compulsory again in public places.

Like many worldwide, Xuan Tu is rolling with the uncertainty triggered by the pandemic.

"This year is now the year we look after our health. Focus on family. The things that are most important," she says.

Vietnam put out this song to teach people how to protect themselves from coronavirus

- Published7 August 2020

- Published15 May 2020

- Published27 June 2020

- Published29 July 2020