Malaysiakini: The upstart that changed Malaysia's media landscape

- Published

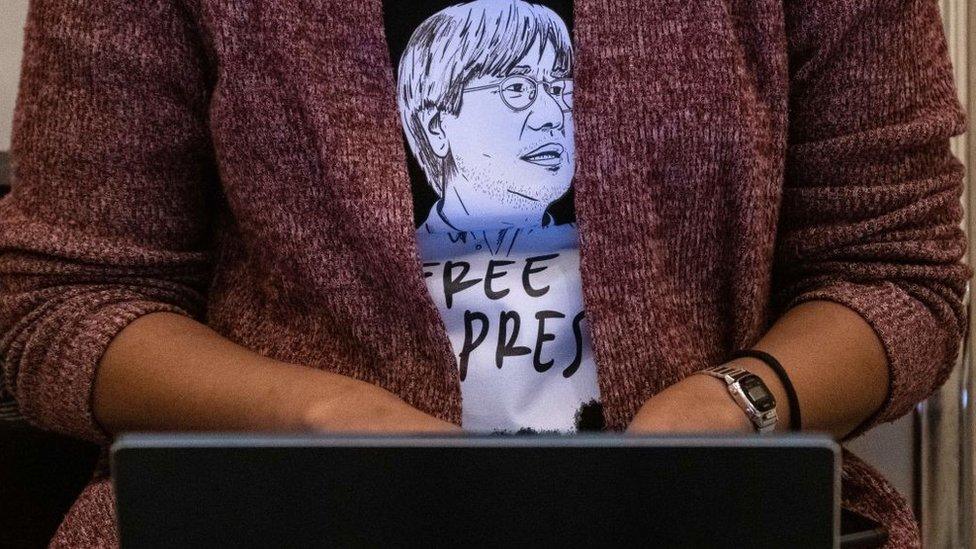

A journalist wears a shirt with an image of Steven Gan

Tucked away in an unremarkable business park in a suburban district of the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur is the headquarters of a remarkable experiment in journalism. It has come under attack.

On Friday the independent news website Malaysiakini was found guilty of contempt. It now has to pay a hefty fine of RM500,000 (£88,500, $123,600) . Its editor-in-chief and co-founder Steven Gan narrowly escaped a prison sentence after he was found not guilty for a similar charge.

The attorney-general filed the charges last year based on readers' critical comments about the judiciary posted on Malaysiakini's website, and later removed, a move with worrying implications for all news media.

Malaysiakini's success so far, its very survival, are all the more remarkable in a country where all news media was once subject to government control, and in a region where truly independent, quality journalism is difficult, dangerous and often driven to the margins.

Steven Gan has been found not guilty of contempt

Back in 1999 Steven Gan and Pramesh Chandran saw an opportunity to create Asia's first online daily news site.

They were both former student activists who worked at Malaysia's The Sun newspaper, and had grown frustrated by official censorship through the requirement to have a licence to publish, and through extensive ownership of mainstream media outlets by pro-government interest groups.

"I was a believer in media freedom, yet we saw its limits in Malaysia every day we worked as journalists", he told the BBC in an interview before the verdict.

The catalyst was the dramatic dismissal and then arrest of Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim in September 1998, a popular figure seen until then as the designated successor to then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, who had been in office for 17 years and dominated Malaysian politics.

It was the start of an epic tussle for power between the two men which would last many years. Steven recalls that several journalists discussed using the then new medium of the internet to report what other media would not.

Steven Gan in 2008

"We realised we could do it for quite a low cost, that, unlike print, we did not need a licence, and Mahathir had already promised foreign investors that he would not censor the internet," he said.

"The internet was very new at that time - you know, we used 56k modems, it was really slow.

"People were really interested in political issues then because of the sacking of Anwar Ibrahim, and we rode on that wave of political awakening. The mainstream media was not reporting what was happening on the ground, especially if there was something like a mass protest in Kuala Lumpur, so they were going to the internet."

Based in the suburban district of Petaling Jaya, Malaysiakini started with just three journalists, initially hoping to fund themselves through partnership with an internet café, then with advertising from internet start-ups during what was then the dotcom boom. It was fortunate to receive a $100,000 grant from the Bangkok-based South East Asia Press Alliance.

It survived the failure of the café, the dotcom bust, and outright hostility from the government, with the Prime Minister accusing Malaysiakini journalists in 2001 of behaving like traitors, and barring them from official press conferences.

Over the years it has endured several police raids, threatened criminal charges and prosecutions. Throughout, said Steven Gan, they insisted their reporters maintain high standards of journalism.

"We are new media but we practise old media rules," he said.

But perhaps the most important decision was an early focus on finding a viable business model for the site, long before other mainstream media had started to question theirs in the digital era.

"We knew we needed to offer a website with reliable information, and we needed to make a political impact," he says.

"But just as important is to have a good business model. You need to have a good editor-in chief, and also a good CEO who can look after the business side of things. The co-founders, myself and Pramesh Chandra, were able to work together to ensure we produce good content, and that we earned enough income to keep the business going."

In 2002 Malaysiakini was among the first news sites anywhere to move to a subscription model, at a time when most viewers expected to get online news for free.

It has been profitable most years, with subscription revenue often matching revenue from advertising. It has been an inspiration to other Malaysian journalists, like Jahabar Siddique, a former Reuters employee, who founded another independent news site, The Malaysian Insider.

"It made it viable for journalists to consider options beyond the muzzled media that was available then. Also made it possible for those like me who were working for international media agencies to consider returning to the local media scene and expand the free space available to inform Malaysians and others about Malaysia."

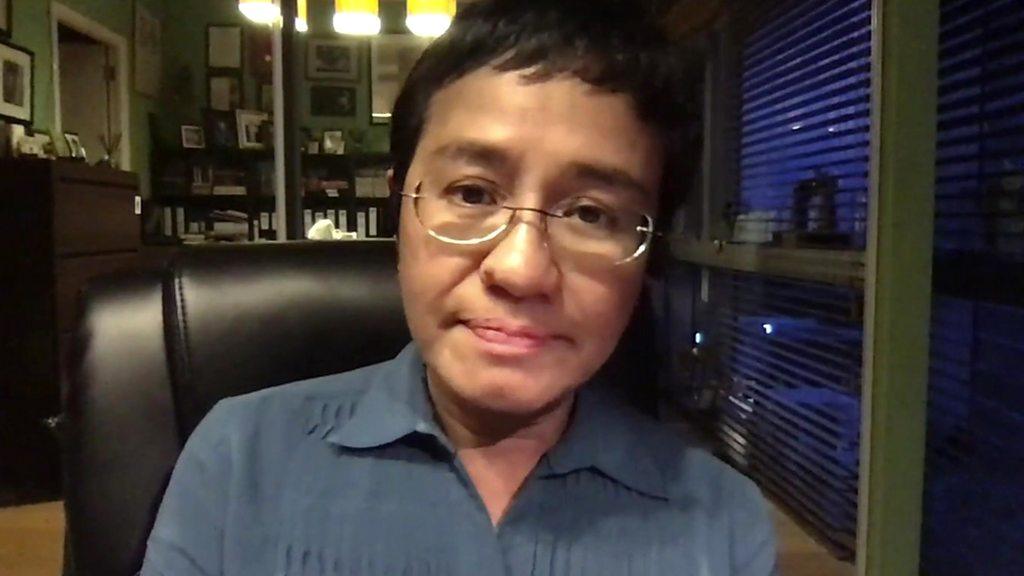

Maria Ressa credits Malaysiakini for showing that an independent news organisation could succeed in the region

Maria Ressa, a former CNN and ABS-CBN journalist who founded the website Rappler in the Philippines in 2012, and now finds herself subjected to several criminal prosecutions under the hostile media climate of the Duterte administration, credits Malaysiakini for showing that a small, independent news organisation could succeed in South East Asia.

"They were the first to embrace a digital platform, and the first to come up with a workable business model for online news. What was so great about Malaysiakini was that from the start they set themselves high standards of journalism, and when faced with pressure from the government, they did not buckle. They never gave up."

On the day of his release from second spell in prison in 2018, Anwar Ibrahim thanked Malaysiakini for ensuring dissenting voices were heard. "You have done a wonderful job. At a time when we had massive restrictions, where the media was nothing but incessant propaganda, Malaysiakini was there."

Anwar Ibrahim has praised Malaysiakini

Malaysiakini has been favoured by a less repressive environment than in many neighbouring countries, and a more favourable economic one.

There is a large and educated middle class in Malaysia, not just keen to read alternative views but to pay subscriptions, or to donate, as they did when the news site needed a new office seven years ago and offered a wall of 1,000 bricks to donors willing to give RM1,000 (£188) a brick.

It has created successful subsidiary businesses, like its advertising arm, which has steadily driven up commercial income. But its real achievement, says Professor Zaharom Nain at Nottingham University's Malaysia Campus, is broadening the political debate in Malaysian society.

"It has, I believe, provided Malaysians with a different way of interpreting Malaysia's politics. It has also paved the way for other news portals to emerge and develop. It has even made mainstream media move to another platform, utilising the internet, for getting their message across," he says.

"Beyond providing dissenting news, Malaysiakini has shown many Malaysians that there is more than one point of view, and that it is legitimate to question authority."

Muhyiddin Yassin's government is proving less tolerant of critical reporting

Today Steven Gan is not alone in finding himself subject to criminal investigation.

Last year six journalists from Al Jazeera were questioned by police over a report on the alleged mistreatment of migrants in Malaysia during Covid-19, on suspicion of violating three laws. Two other journalists were also investigated for their reporting.

Following the collapse of the reformist government headed by Mahathir Mohamad after his comeback in the 2018 election, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin now heads a precarious coalition pulled together last March.

Mr Muhyiddin's government is proving less tolerant of critical reporting than its predecessor in what is now a more heated and less predictable political climate.

- Published25 June 2020

- Published25 July 2020

- Published5 March 2020