Singapore: Why these defiant 'nail house' owners refuse to sell

- Published

From reel life to this real life scenario in Singapore

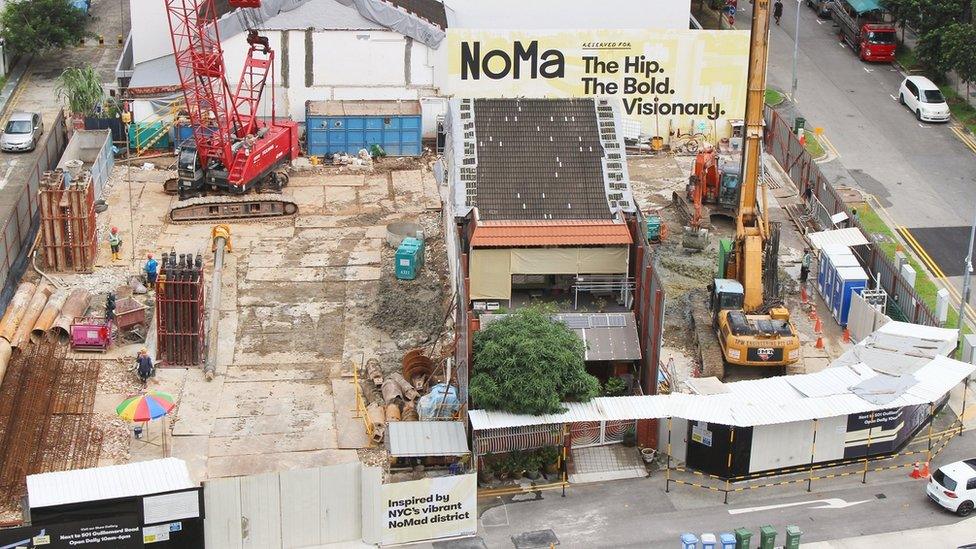

It is hard to miss the two little houses sitting defiantly in the middle of the Singapore building site.

It's instantly reminiscent of the award-winning cartoon Up, the Pixar film which tells the tale of an old man who refuses to move from his home as towering blocks of flats rise around him.

Indeed, the owners of these two homes are just as determined to stay put, refusing offers reportedly worth millions to move elsewhere.

But unlike the cartoon hero, who eventually floats off to a new life, the owners of these houses - dubbed "nail houses", as they refuse to be hammered down - are going nowhere.

'I can't find such a house'

"I won't sell it no matter how much money the other party offers," the 60-year-old owner of 54 Lorong 28 Geylang told local media outlet Shin Min.

"I turned the open space in front of a house into the garden. I have potted plants, I raise fish and birds and sit here in the morning as the city wakes up.

"I can't find such a house now. It's a freehold land that belongs to us."

The man uses his front garden to raise various pets

And herein lies the crux of the problem: freehold land is especially valuable in Singapore, a city with almost 8,000 people squeezed into every square kilometre, according to the World Bank, where space of any sort is in short supply.

Singapore has over the years engaged in land reclamation - expanding its landmass by more than 20% since its independence in 1965, using imported sand from neighbouring countries - but there is still a serious lack of space.

What's more, most of the developments in Singapore are built on leasehold land which is state-owned, meaning that when the lease expires, ownership of the land goes back to the government.

Properties built on freehold land, however, belong to the home owners indefinitely - and, as a result, can be sold for a much higher price.

In this case, property developer the Macly Group plans to turn this piece of land into The NoMa condominium, 50 units spread across three separate blocks. Here, a four-bedroom unit will set you back at least $1.88m (£1m; $1.36m).

An artist's impression of the upcoming NoMa development

According to a Straits Times report, the Macly Group had to acquire seven houses and tear them down to redevelop the 13,000 sq ft plot.

The Macly Group declined to comment on how many houses were acquired and at what cost. But media reports say it managed to secure five of them for a sum of around S$20.55m.

The final two refused to move - one facing the main street and another facing a side street - upsetting the developer's original plans.

The two houses who have refused to move, outlined in yellow

"[We] could not implement the original designs as a result," a spokesperson from Macly Group told the BBC. "We had to change the design drastically to offer separate accesses for privacy."

And so, these holdouts will become the city's latest nail houses - or dingzihu in Chinese - a home where the owner refuses to accept money from a property developer for its demolition. They often end up surrounded by rubble, or with developers just going ahead and building around them.

When the house is built, it will be sandwiched by a luxury apartment

But there is more than meets the eye here. The property at 337 Guillemard Road, which will find itself right in the middle of the NoMa development, is reportedly not a home, but a Buddhist temple hall open only to the owner's family and friends.

According to Prof Ho Puay-peng, of the National University of Singapore, it is not uncommon for private houses to be used as religious sites, as smaller organisations might not have the financial means to purchase a bigger building.

The house is used as a Buddhist temple hall

"Geylang probably has the highest density of small clan and religious organisations in the whole of Singapore. It's not uncommon for them to just convert one floor of a house into a religious venue," says Prof Ho.

When the BBC visited the site last month, a middle-aged man declined an interview request.

It's likely that when the luxury development is fully built, the temple hall will sit in the shadows of the flats - with the residents there possibly able to look straight down on the home.

The development will tower over both houses

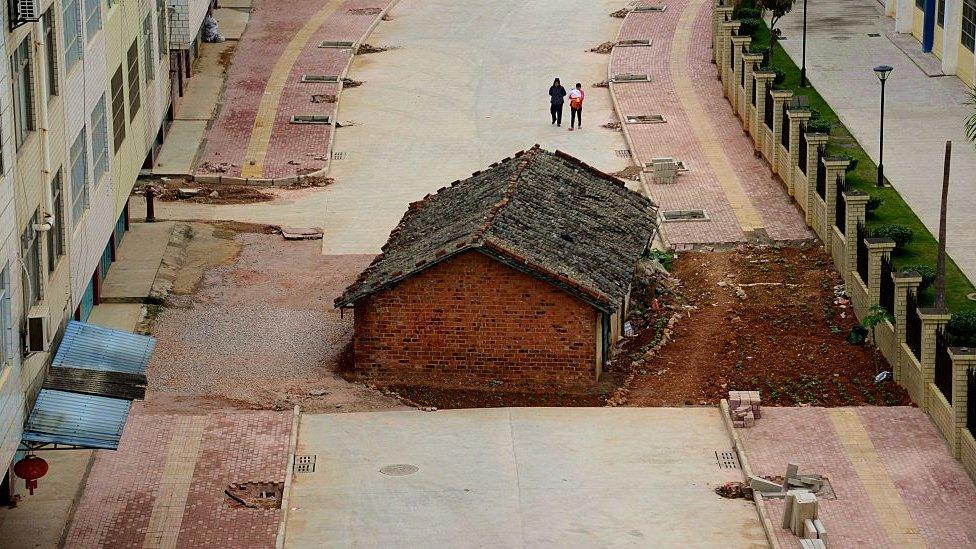

These two buildings stand out for another reason. Nail houses are rare in Singapore. Examples are far more common in China, where a home remained standing in the middle of a shopping mall in Changsha, while in Shanghai, a home sat in the middle of a road for 14 years before it was demolished.

This is because, Prof Ho explains, "planning guidelines from the Urban Development authority try to prevent such situations from arising" in Singapore.

A nail house pictured in 2015 in Nanning, southern China

"For example, if you want to redevelop terrace houses into flats, there is a certain minimum size... and safeguards [in place]," he says. "In this case... it's likely that the [owners of the two houses] would have to sign a waiver to say they are happy for the [development] to be built around them. If not it's likely the development will not be able to go ahead."

The Macly Group told the BBC that the two houses in question had "no objection that we proceed with our plans".

You may also be interested in...

Road built around house as Chinese couple refuse to move

- Published18 September 2017

- Published28 May 2015

- Published1 December 2012

- Published13 August 2013

- Published15 September 2018