The K-pop inspired band that challenged gender norms in Kazakhstan

- Published

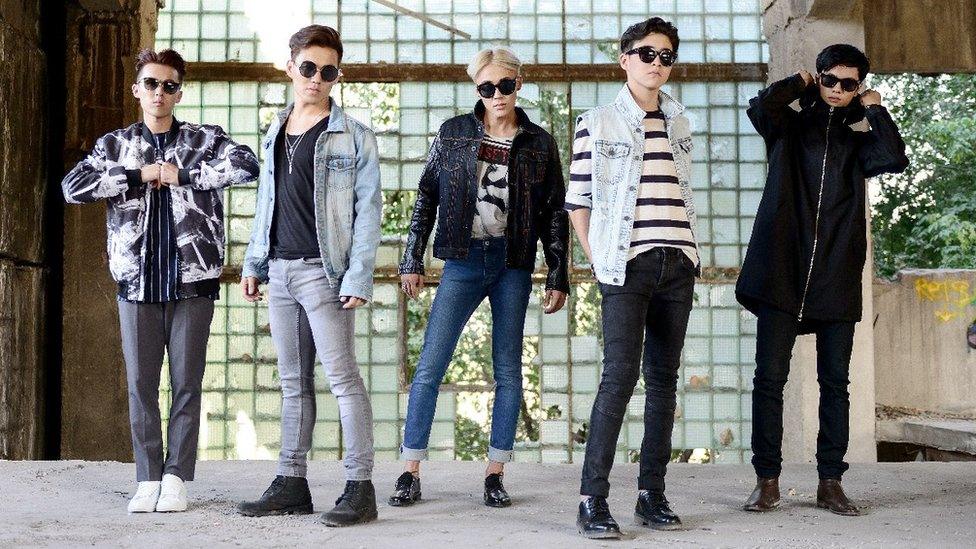

(From L-R) Zaq, Bala, Ace, Alem in 2020, with band member A.Z having left the group this year

They made their debut as a boy band, expecting to create music and amass fans along the way. Instead they were met with anger, protests and even threats.

They perform choreographed dance routines, sing addictive tunes and have shockingly slick music videos - and no, we're not talking about a K-pop group.

This is Q-pop, or Qazaq-pop - an up and coming pop genre in Kazakhstan, which all started with one band, Ninety One.

But the band has not only made a name for itself through its music.

It also made a huge statement when its five androgynous looking members - complete with long hair, guyliner and makeup, burst onto the scene in the deeply conservative country - and challenged its gender norms.

How it all began

In 2014, an entertainment group in Kazakhstan held a singing competition - looking for talented individuals who could form a band.

Four boys - A.Z. and Zaq were selected, with Bala and Alem cast separately. They were joined by Ace, who had come from South Korea's famous SM Entertainment - the group behind some of the country's most popular K-pop acts.

"We became a team, wrote songs together, learned to dance and perform, and finally... debuted when we were ready," the band told the BBC in an email interview.

But the band's producer and the man responsible for creating the group, Yerbolat Bedelkhan, wanted more than just one band.

His aim was to create a whole new genre of music in Kazkahstan, known as Q-pop, or Qazaq pop, inspired by K-pop.

Although it has now swept the globe, back in 2014 K-pop was arguably less well known in the West although it had a massive Asian following.

"Ninety One were conceptualised as a domestic version of K-pop and to some extent are a manufactured group," said Megan Rancier, Associate Teaching Professor of Ethnomusicology at Bowling Green State University.

Ninety One with its androgynous looking members challenged Kazakhstan's gender norms

But when they made their debut, their appearance was a shock to many in the highly conservative country.

"The boys dressed in brighter colours, skinny jeans... their style was more provocative," Mr Bedelkhan told the BBC.

"When they went outside they were dressed in a way that people in the street don't usually dress. In our country, it's not accepted that men can dress brightly."

People were so scandalised there were even protests, demanding the cancellation of their concerts and calling them "gay".

"People in Kazakhstan are very protective of what they believe Kazakh men and women look like," Aizada Arystanbek, a Kazakhstani gender-related issues specialist told the BBC.

"People's bodies and behaviour is policed by the public in a sense that there is always this notion of 'Is that a Kazakh thing to do?'"

Many of those who protested were young men.

"My father served in the army. When I show his photo, I am proud to say that... he's a real man. What about Ninety One?" one student against Ninety One says in a documentary about Q-pop, titled "Face the Music". , external

"I can't say they are not men, but they can't be called men either."

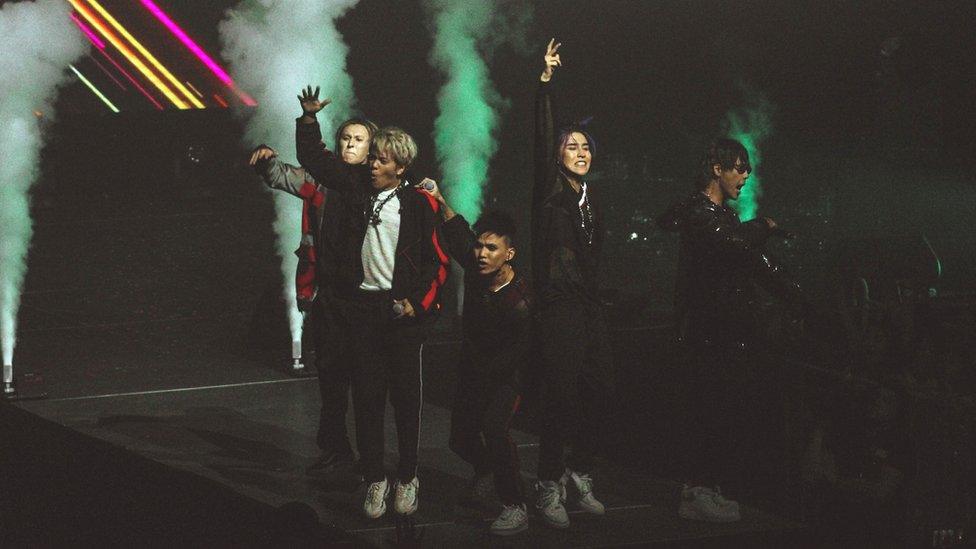

The band's performances have drawn large crowds in Kazakhstan

Ninety One's concerts were eventually cancelled. In one case, a city's authorities pre-emptively cancelled a concert, saying they anticipated protests.

The band also revealed that they received anonymous threats, with some people threatening to "rip up our bellies".

And that was not all.

The phrase "Ninety One" became synonymous with dressing flamboyantly, or being gay - and was quickly used as an insult.

"We heard stories that these guys [described as 'being Ninety One'] were even beaten in the street," said Mr Bedelkhan. "I myself witnessed this kind of event."

According to Prof Rancier - what it came down to ultimately, was not only how they dressed - but what exactly that symbolised.

"There is a nationalistic edge to the monitoring of gender norms because it relates to what is perceived as correct behaviour for a 'real' Kazakh man or woman," she said.

"Divergence from this signals not only a subverting of tradition, but potentially also abandonment of one's cultural/national roots."

She adds that the opposition mostly centred in more "conservative communities - generally rural", though as a whole, gender norms in Kazakhstan still remain "fundamentally very traditional".

One socialist researcher interviewed in the documentary, said a lot of the backlash against Ninety One was from young people whose parents had moved from rural areas.

"[Those growing up in the city] they are more open... being multicultural for them is absolutely ok. On the other hand, there are young people [from more rural areas] who are very traditional, it is them who are now promoting conservative values in society. Ninety One is the acid test that helps identify which group a young person belongs to."

'Soft boys' and hyper masculinity

Eventually, opposition against the band died down and they began to gain popularity.

"[The] Kazakh urban youth already knew and liked K-pop, so this gave them an opportunity to enjoy homegrown bands producing music that was more 'for them'", said Prof Rancier.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The modern music scene has in recent years been diversifying across Kazakhstan, though the band says this wasn't the case when they were growing up.

"[Growing up], we mainly listened to foreign music because we didn't have any artist examples in Kazakhstan. The local music was focused on toi - a genre of folk music - and artists could only make money this way."

"Ninety One offered a modern product... which helped them gain a significant fanbase among youth," said Sabina Insabayeva, a postdoctoral fellow affiliate at the National University of Singapore.

Ms Arystanbek added that Ninety One's presence also disrupted the music scene in Kazakhstan, which is typically made up of "very gender normative bands".

Folk music is popular in Kazakhstan

"[Ninety One] definitely brought the culture of 'soft boys' to Kazakhstan...[they] were not trying to appear hyper masculine or assert their masculinity in the way they looked," she said.

"They are one of the first ones to do that in the music scene...[and] the fact that they gather thousands of people in their stadiums could tell us that the Kazakhstani public is more accepting of non-hegemonic masculinity now more than ever."

Today, there are dozens of Q-pop bands in Kazakhstan - all inspired by the initial success of Ninety One.

And Q-pop has since spread across the region, gaining popularity in nearby countries like Turkey, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. But it's also managed to gather fans worldwide.

Kalina D'Souza, an Indian national who lives in Kuwait, told the BBC she came across Q-pop when watching a video on YouTube.

"Since I was already into K-pop before this, I ended up liking Q-pop when I explored further," she said.

"While it does bear resemblance to K-pop, they manage to execute unique concepts. You can tell a lot of work has gone into the music."

According to Prof Rancier, both genres share elements like being single-sex groups, and members are typically young and good-looking.

The band in 2018

But the band's key difference is its motivation to promote the Kazakh language.

Part of the former Soviet republic, Kazakhstan lies on the border with Russia. A census in 2009 showed , externalthat only 62% of the population could speak and written fluent Kazakh, as opposed to 85% in Russian.

The Kazakh government has been trying to promote the use of Kazakh - even banning the use of Russian in its cabinet meetings in 2018.

"Q-pop has been considered a tool to construct [Kazakhstan's] national culture, while K-pop is more of a cultural product driven by private companies," K-pop expert Professor Lee Gyu-tag told the BBC.

Opening up a conversation

But has Q-pop done anything to change gender norms in Kazakhstan?

Dr Insebayeva says that while the band has definitely added to the conversation, there is still a "significant number of people" who still reject how Ninety One look.

"While it can't be denied that the band presented a popularised alternative image of Kazakh masculinity, more time needs to pass to examine whether existing gender norms have been drastically shifted," she said.

But there's no denying that the band definitely have taken the first steps needed for such a conversation to happen.

"[While] I don't think they have actually changed gender norms... [they have] challenged conventional gender norms in terms of their appearance and behaviour," said Prof Rancier.

"They have presented an alternative version of how a Kazakh man can look and act - and thus opened up the conversation [about this]".

Related topics

- Published12 July 2019

- Published14 October 2020

- Published15 October 2020

- Published18 October 2019