Covid and suicide: Japan's rise a warning to the world?

- Published

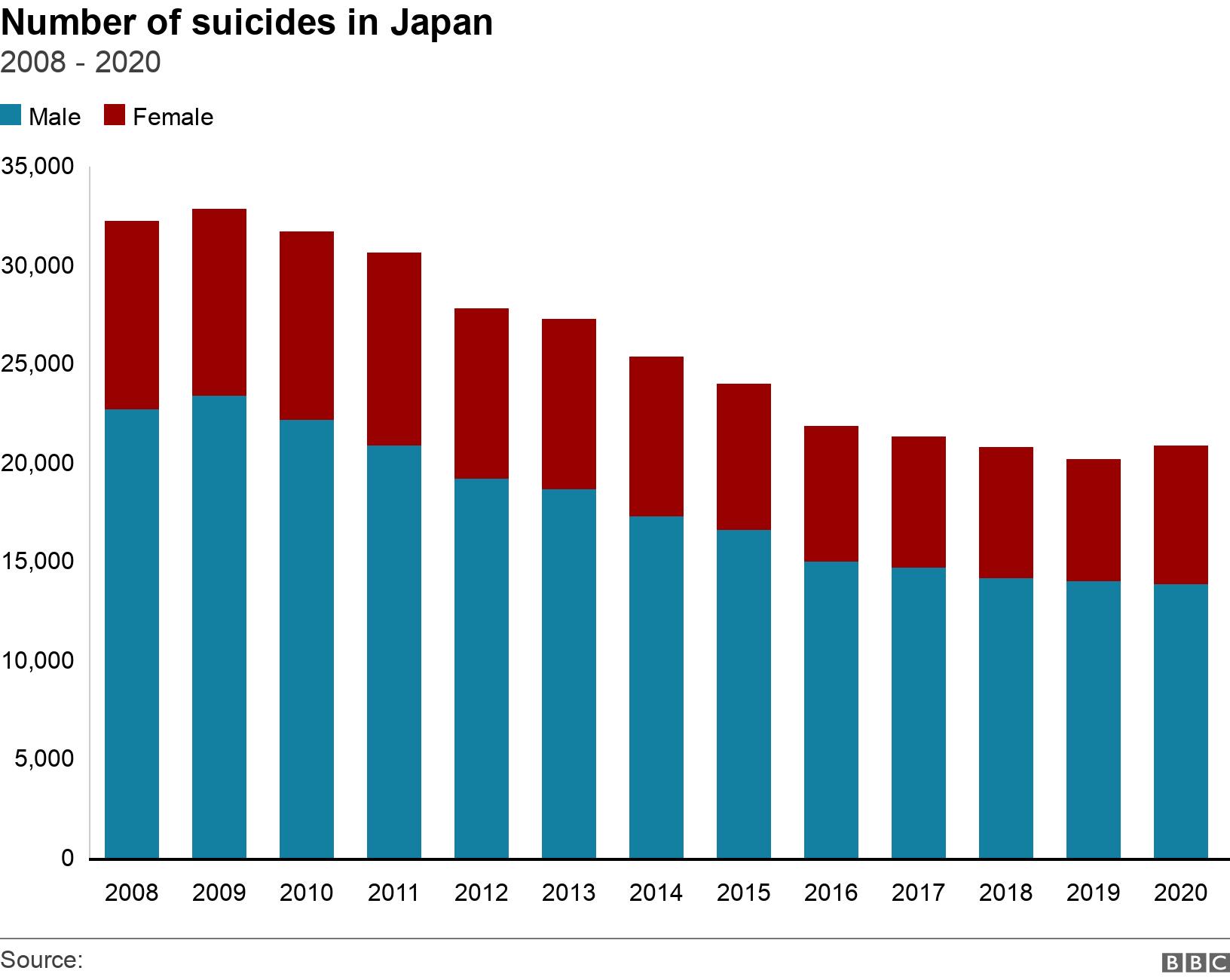

Japan reports suicides faster and more accurately than anywhere else in the world. Unlike most countries, here they are compiled at the end of every month. During the Covid pandemic the numbers have told a disturbing story.

In 2020, for the first time in 11 years, suicide rates in Japan went up. Most surprising, while male suicides fell slightly, rates among women surged nearly 15%.

In one month, October, the female suicide rate in Japan went up by more than 70%, compared with the same month in the previous year.

What is going on? And why does the Covid pandemic appear to be hitting women so much worse than men?

Warning: Some may find the content of this story upsetting

Meeting face-to-face with a young woman who has repeatedly tried to kill herself is a troubling experience. It has given me new respect for those who work on suicide prevention.

I am sitting in a walk-in centre in Yokohama's red-light district, run by a suicide prevention charity called the Bond Project.

Across the table is a 19-year-old woman, with bobbed hair. She sits motionless.

Quietly, without any emotion, she starts to tell me her story. It started when she was 15, she says. Her older brother began violently abusing her. Eventually she ran away from home, but it didn't end the pain and the loneliness.

Ending her life seemed the only way out.

"From about this time last year I have been in and out of hospital many times," she tells me. "I tried many times to kill myself, but I couldn't succeed, so now I guess I have given up trying to die."

What stopped her was the intervention of the Bond Project. They found her a safe place to live, and began giving her intensive counselling.

Jun Tachibana is the founder of the Bond Project. She is a tough woman in her 40s with relentless optimism.

Ms Tachibana hopes the Bond Project provides women with the help they need

"When girls are in real trouble and in pain, they really don't know what to do," she says. "We are here, ready to listen to them, to tell them - we are here with you."

Ms Tachibana says Covid seems to be pushing those who are already vulnerable closer to the edge. She describes some of the harrowing calls her staff have received in recent months.

"We hear lots of 'I want to die' and 'I have no place to go'," she says. "They say 'It is so painful, I am so lonely I want to disappear'."

For those suffering physical or sexual abuse, Covid has made the situation much worse.

"A girl I talked to the other day said she is getting sexually harassed by her father," Ms Tachibana tells me. "But because of Covid her father is not working so much and is at home a lot, so there is no escape from him."

A 'very unusual' pattern

If you look at previous times of crisis in Japan, such as the 2008 banking crisis or the collapse of Japan's stock market and property bubble in the early 1990s, the impact was largely felt by middle aged men. Large spikes were seen in male suicide rates.

But Covid is different, it is affecting young people and, in particular, young women. The reasons are complex.

Japan used to have the highest suicide rate in the developed world. Over the last decade it has had great success in reducing suicide rates by around a third.

Professor Michiko Ueda is one of Japan's leading experts on suicide. She tells me how shocking it has been to witness the sharp reverse in the last few months.

"This pattern of female suicides is very, very unusual," she tells me.

"I have never seen this much [of an] increase in my career as a researcher on this topic. The thing about the coronavirus pandemic is the industries hit most are industries staffed by women, such as tourism and retail and the food industries."

Japan has seen a large rise in single women living alone, many of them choosing that over marriage which entails quite traditional gender roles still. Prof Ueda says young women are also far more likely to be in so-called precarious employment.

Prof Ueda calls the pattern of female suicides "very unusual"

"A lot of women are not married anymore," she says. "They have to support their own lives and they don't have permanent jobs. So, when something happens, of course, they are hit very, very hard. The number of job losses among non-permanent staff are just so, so large over the last eight months."

One month really stands out. In October last year, 879 women killed themselves. That is more than 70% higher than the same month in 2019.

Newspaper headlines sounded the alarm. Some compared the total number of suicides by men and women in October (2,199) to the total number of deaths in Japan from Coronavirus up to that point (2,087).

Something particularly strange was happening.

On 27 September last year, a very famous and popular actress named Yuko Takeuchi was found dead at her home. It was later reported that she had taken her own life.

Japanese actress Yuko Takeuchi was found dead at her own home at 40

Yasuyuki Shimizu is a former journalist who now runs a non-profit organisation (NPO) dedicated to combatting Japan's suicide problem.

"From the day the news of a celebrity suicide is reported, the number of suicides increases and stays that way for about 10 days," he says.

"From the data we can see that the suicide of the actress on 27 September led to an extra 207 female suicides in the next 10 days."

If you look at the data for suicides by women around the same age as Yuko Takeuchi, the statistics are even more stark.

"Women in their 40s were most influenced out of all the age groups," Mr Shimizu says. "For that group it (the suicide rate) more than doubled."

Other experts agree that there is a very strong connection between celebrity suicides and an immediate uptick in suicides in the days following.

The celebrity phenomenon

This phenomenon is not unique to Japan, and it is one reason why reporting on suicide is so difficult. In the immediate aftermath of a celebrity suicide, the more it is discussed in the media, and on social media, the greater the impact on other vulnerable people.

One of the NPO's researchers is Mai Suganuma. She is herself a victim of suicide. When she was a teenager, her father took his own life. Now she helps to support the families of others who have killed themselves.

And just as Covid is leaving relatives unable to grieve for those who have succumbed to the virus, so it is making life for the families of suicide victims much more difficult.

"When I talk to the family members, their feeling of not being able to save the loved one is very strong, which often results in them blaming themselves." Mai Suganuma tells me. "I too blamed myself for not being able to save my father.

"Now they are being told they must stay at home. I worry the feelings of guilt will grow stronger. Japanese people don't talk about death to begin with. We do not have a culture to talk about the suicides."

Japan is now in a so-called third wave of Covid infections, and the government has ordered a second state of emergency. It is likely to be extended well into February. More restaurants and hotels and bars are closing their doors. More people are losing their jobs.

The third wave of the virus has caused Japan's streets to once again fall empty

For Prof Ueda there is another nagging question. If this is happening in Japan, with no strict lockdowns, and relatively few Covid deaths, then what is happening in other countries where the pandemic is much worse?

If you have been affected by the issues raised in this article, help and support can be found at this BBC Action Line.

If you are in Japan you can contact the Bond Project, external, Japan Suicide Countermeasures Promotion Center, external or Life link, external.

Related topics

- Published27 September 2020

- Published3 July 2015

- Published10 November 2017

- Published5 January 2021