North Korea’s ‘only openly gay defector’ finds love

- Published

Jang Yeong-jin's remarkable story as North Korea's only openly gay defector was covered by the international media after he published his autobiography. Now, almost a quarter of a century after fleeing the country, he tells the BBC that he plans to marry his American boyfriend.

Jang Yeong-jin had never found women attractive. But it wasn't until his wedding night, aged 27, that this made his life difficult.

Jang felt intensely uncomfortable. "I couldn't lay a finger on my wife," he recalls. Although the couple did eventually consummate their marriage, sex was rare. Four years later - his wife still not pregnant - one of Jang's brothers began to quiz him. Jang admitted he had never been aroused by the opposite sex, and his brother promptly sent him to a doctor.

"I went to so many hospitals in North Korea because we thought that I had some sort of physical problem."

It never occurred to Jang, or his family, that there could be another reason for his lack of interest.

Medical tests

"There is no concept of homosexuality in North Korea," he says. If someone is seen running to greet another same sex friend, it's assumed that's just because they have such a close friendship. In fact adults of the same sex often hold hands in the street, he says. "North Korea is a totalitarian society - we have lots of communal life so it's normal for us."

Jang now thinks his experience of being misunderstood was by no means unique.

At one point, Jang was admitted to hospital for a month of tests and got to know some of the other patients. "I figured out many of them had a similar experience to me - people who could not feel anything towards women."

But articulating, or exploring, what it was they did feel, was likely to have been impossible without a frame of reference.

"In North Korea, if a man says he doesn't like a woman, people [just] think he's unwell."

One man Jang had served with in the military visited him several times after they were discharged. He confided that his wedding night, too, had been a disaster - he couldn't bring himself to even hold his wife's hand.

"I think he was also someone like me," reflects Jang.

Park Jeong-Won, a law professor at Seoul's Kookmin University, says that he is not aware of any explicit North Korean law against gay and lesbian relationships. But he adds that the state's laws against extramarital relations and breaching social mores would probably be co-opted into prosecuting any gay sexual act.

Another academic in Seoul, Kim Seok-hyang, has interviewed dozens of defectors on the subject, and says not one of them had even heard of the concept.

"When I asked them about homosexuality, they didn't catch on quickly so I had to explain it to every single person," Kim, professor of North Korean Studies at Ewha Women's University, says.

The defectors all told her they were certain that anyone found exploring same-sex relationships would be ostracised at the very least, possibly even executed.

Jang was released from hospital with a clean bill of health - all the medical tests set in motion by his brother's intervention showed there was nothing physically wrong.

But his wife remained extremely unhappy.

"I thought: 'I should let this person go. We should find a way to be happy for each other,''' Jang says.

So Jang filed for divorce. But this process is not straightforward in North Korea. Permission needs to be granted by the courts, and they prioritise the family unit, says law professor Park Jeong-Won. They will only authorise a split if the union is seen to threaten the country's ideology, he says.

Jang began to realise he had only one option left - to leave North Korea altogether. This would automatically void their union and allow his wife to remarry.

But the final catalyst for his defection was a visit from Jang's best friend, a man called Seoncheol. They had grown up together in their northern hometown of Chongjin. The two had always been close, sharing a bed on boyhood sleepovers. But as they had got older, Jang's feelings for Seoncheol had intensified.

"I really liked Seoncheol so much. I still see him in my dreams."

From time to time Seoncheol would come to dinner, and on one particular evening Jang, concerned that it had got late, persuaded Seoncheol to stay over. A few hours later, Jang found himself creeping out of his own bed and in beside Seoncheol. He was devastated when his sleeping friend didn't so much as stir.

"I don't know what I wanted from him exactly - maybe I just wanted him to hug me tight," says Jang.

But the moment crystallised his feeling that his life in North Korea had come to an end.

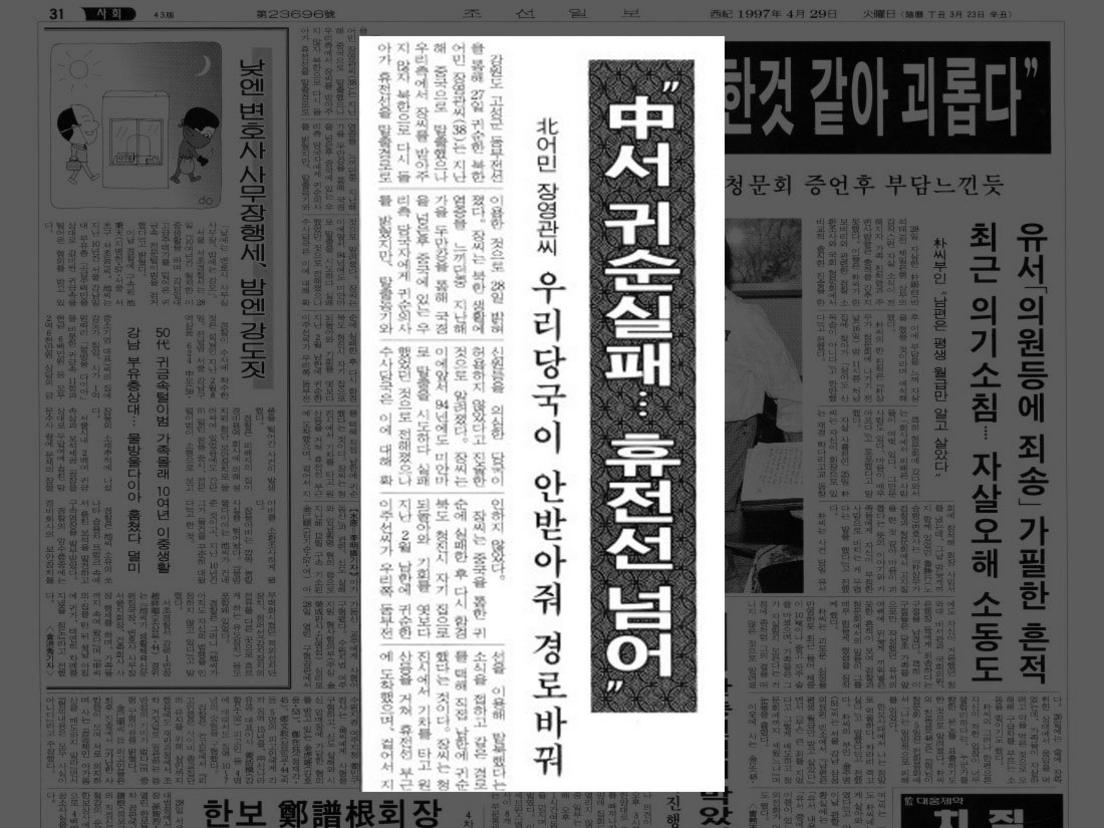

Jang arrived in South Korea in April 1997 by crawling across the mine-strewn de-militarized zone (DMZ) that divides the two nations, after his initial route left him stranded in China. Crossing the DMZ is so risky and rare that his escape made headlines in the South.

Jang escaped across the heavily fortified DMZ

The atmosphere in Seoul was a world away from the isolationist North, but even here he baffled officials. Every defector who arrives from the North undergoes several weeks of compulsory grilling by the South Korean national intelligence service (NIS) - to check they are not spying for the North. But Jang was questioned for more than five months, having initially baulked at explaining the real reason why he defected. When he finally admitted he was simply not attracted to his wife, he was allowed to stay - but once again was sent to a doctor.

"The [NIS] official told me that there should be a reason to dislike women."

Even in the South at that time, there was little public awareness of different sexual orientations. A few doctors recommended he seek psychological help - advice he ignored.

And then in the spring of 1998, 13 months after he first arrived in South Korea, Jang opened a magazine to read the write-up of an interview he had given about his defection across the DMZ. He turned the page to discover an article about gay men coming out, with a scene from an American film showing two men kissing in bed.

Jang's risky defection route made headlines in the South

Finally it dawned on Jang that he, too, was gay.

"When I saw that, I knew right away that I was this kind of person. That's why I couldn't like women."

The revelation transformed Jang's life, and he became a regular at Seoul's gay bars.

But a few years later, this new world exposed Jang to devastating fraud. In 2004, the owner of Jang's favourite bar introduced him to a local air steward. They dated for three months and Jang fell in love. The air steward urged Jang to move in, but explained that as he lived with his stepfather they would first need to buy a bigger home. Jang moved out of his own rental and gave him all 90m won ($81,669) of his hard-won savings and all his belongings.

Jang never saw the man again. He went to the police station every day for 15 days until the police told him he should give up.

Jang says it never occurred to him that he could be cheated in this way.

"In North Korea, we live a very controlled life, so if I said I was duped by someone, the party would track him down and punish him hard."

Jang fell ill and had to be hospitalised for a month, which he now thinks was triggered by stress. This meant he lost his job in a factory and was now penniless, homeless and unemployed, in a social climate which has proved a tough welcome for North Koreans.

As he slowly rebuilt his life, taking a job as a cleaner and painstakingly saving enough money to rent a new home, he began to spend his free time writing.

As a boy, he had once won first place in a writing contest, but it had been a requirement that students only wrote in praise of the North Korean regime. Now, finally, Jang could write whatever he wanted. His autobiography A Mark of Red Honor was published in 2015.

But it took a long time for Jang to risk dating again. And then last year, at the age of 62, Jang met Korean-American restaurant owner Min-su on a dating site. Just four months later, he was on his way to the nation he once knew only as "the country of wolves" - Pyongyang's derogatory term for the US.

But when Jang saw Min-su waiting for him in the arrivals hall, his heart sank. Min-su was in shorts and cap, and Jang was not impressed.

"Seeing how he dressed, I assumed he was an ill-mannered and blunt man," Jang says.

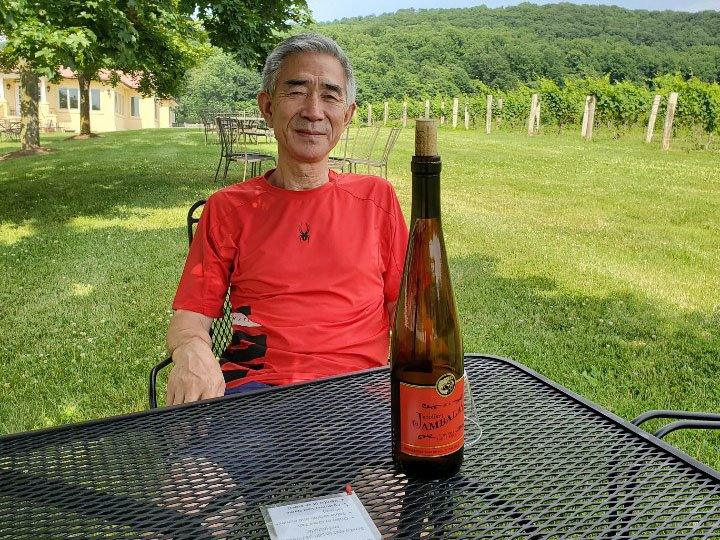

The coronavirus lockdown gave the pair the space to get to know each other properly, with picnics and wine drinking.

"The more I got to know this man, the more I could see that he had a very good character. Although he is eight years younger than me, he is the kind of person who likes to care for others first."

After about two months Min-su decided to propose.

Jang is now in the process of finalising documents to prove his first marriage in North Korea is over, and they hope to marry later this year.

"I always felt fearful, sad and lonely when I lived alone. I am a very introverted and sensitive person, but he is an optimistic man, so we are good for each other," he says.

Jang and his fiance

But despite his new-found happiness, Jang remains haunted by the impact his defection had on his family. Several of his relatives were banished to a remote village in the freezing north, a brutally familiar fate for those whose family members are perceived to have been disloyal to the regime. Six of his relatives died from hunger and illness, including his mother and four of his siblings.

Jang says the only way he can cope with the guilt is by committing his thoughts to pen and paper.

"Whenever I think of my family, it is too painful for me, so I decided to write. I believe that is now the only way that I can make it up to them.

But he is comforted that his decision to leave North Korea gave his wife new opportunities. He has heard that she has remarried.

"I always thought she was very talented, so I feel so happy for her."

And he says he is looking forward to expanding his horizons once the coronavirus lockdown eases and wants to visit Washington - half an hour's drive away - with Min-Su.

"I heard that there are many gay bars there. I want to go to those bars with him."

In the meantime, he says he is enjoying the serenity of the suburbs, which he describes as like being in a "fairytale".

We have given Min-su an assumed name, at his request