Hunting rare birds in Pakistan to feed the sex drive of princes

- Published

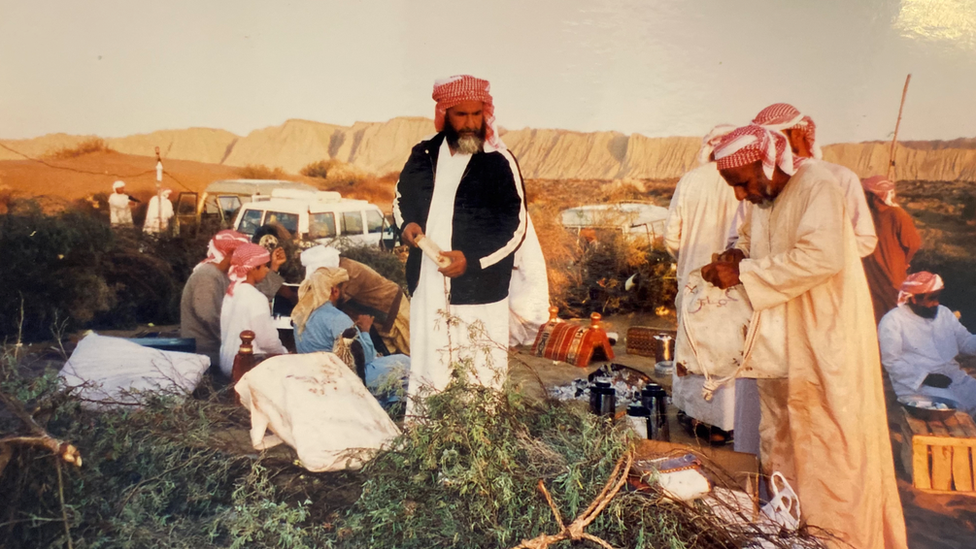

A group of hunters from Abu Dhabi, pictured in Pasni in the late 1980s

In 1983, two army officers stopped at a car rental office in Pasni, a small coastal town in south-west Pakistan.

One of them asked the owner: "Do you have a good car? We have to take an Arab sheikh to Panjgur."

The owner told them he did and sent his son Hanif to show it to them.

The vehicle was for Prince Suroor bin Mohammed al-Nahyan, who belongs to one of the six royal families of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). He wanted to get to Panjgur, about 100km (65 miles) inland, to hunt houbara bustards, rare birds whose meat is considered by some to be an aphrodisiac.

The sheikh liked the car - and he took to Hanif, who was then 31. So started a long friendship, says Haji Hanif, as he's now known. Thirty-seven years on, he is one of the caretakers for the royals who come every year to Pakistan to hunt houbaras.

A falcon preys on a houbara bustard (file photo)

The shy birds, about the size of a turkey, are in decline, so killing them is controversial - but they are still hunted for sport.

Powerful interests in Pakistan support the secretive hunts, which have been going on for decades, as a way of furthering relations with influential players in rich Gulf states. Those who back the trips say they bring desperately needed employment and investment.

But what Pakistan actually gains is not all that clear. Some in hunting circles say royals use the trips purely for personal enjoyment.

Every year between November and February, Haji Hanif welcomes royal parties who flock to his part of Balochistan province, about an hour's drive east from the strategic port of Gwadar.

Before this winter's hunts ended, he invited the BBC to see the meticulous preparations he and his staff make for the royals. The lavish reception stands out in a place like Pasni, where basic necessities are still a far-off dream for most locals.

We were met by two men who guided us to Haji's palatial mansion, an easy drive past residential compounds a few kilometres from the airport road. The number plate of the men's jeep was registered in the UAE, which made it seem like we were in a little part of Abu Dhabi.

The Abu Dhabi sign welcomes visitors to Haji Hanif's property

This feeling was strengthened by the huge sign of Abu Dhabi royalty, complete with eagle on top, that we saw as we entered the house, sitting like an oasis in an otherwise barren and poor neighbourhood.

The visiting royals provide employment for several dozen local people. As we arrived, we could see men busy with the sheikh's falcons, while others cleaned the kitchen or fixed the SUVs in a giant garage.

A man dressed in khaki led us to the guest quarters where a waft of ittar (perfume) welcomed us inside.

"How do you like our place?" asked Haji Hanif, who was sitting on one of the sofas.

Haji Hanif has spent most of his life serving royals from the UAE

Now in his late 60s, Haji is a storyteller with a disarming presence. As he showed us around, he told us about the sheikh's visits over the years.

"After we helped him get the car, he came back to us again. By 1988, my father and I were managing 20 of the sheikh's cars because he trusted us with them."

For Pasni, the visits generate income for some 35 locals who are employed three months before the royals arrive.

As well as the men who look after the falcons, and the pigeons used to help train them, three are assigned to the garden where lemons are grown for the sheikh. Another is in charge of laundry.

Others take care of cooking and cleaning, and looking after the vehicles. A man on a motorbike is paid to tour the vicinity spotting houbara bustards, so the sheikh doesn't have to drive too far.

Haji Hanif's three sons are employed to help their father.

The eldest looks after the garage and the 20 SUVs kept for the sheikh's use, the middle son works as his bodyguard, in charge of security, and the third makes sure houbaras aren't poached or sold on the black market by locals.

Pakistan started inviting royals in 1973. Numerous private parties began travelling from the Gulf to hunt the houbara bustard, a migratory bird that comes to the south-west of Balochistan in winter.

By 1989 the provincial government, backed by federal authorities in Islamabad, had formalised the arrangement, allocating different locations to different royal families.

Pasni, Panjgur and Gwadar were designated for royals from the UAE. Jhal Jhao in Awaran district to the east along the coast was for sheikhs from Qatar. And Chaghi, further north, was assigned to the royal family of Saudi Arabia. Families such as Haji's were allotted as caretakers to the royal families at this time too.

Back in the 70s, the hunting parties would camp wherever the houbaras were. The hunts would typically last about a week and the royals would cook and eat the birds in the camps before heading back to town.

The meat of the houbara is thought by some in Arab countries to be an aphrodisiac

But security concerns in south-west Balochistan, where an armed separatist insurgency has raged for years, means it's no longer safe to camp in the middle of nowhere. Royal family members now mostly stay in hotels or homes made to their liking, of the kind provided by Haji Hanif. From there, it's a few minutes' drive into the desert to hunt birds that have already been found by employees.

Traditionally falcons would chase the highly prized houbaras - the bird's throat would be slit with a knife once it had been caught. Hunters would also shoot the birds. These days, because of poaching, caretakers often get hold of the houbaras first and release them for the falcons only once the hunters are present.

The royal entourage, seen here in the late 1980s, used to camp on the outskirts of Pasni and cook birds they killed

The hunting of houbara bustards, also known as Asian houbaras, has long been a contentious issue. They once flourished on the Arabian peninsula. But the International Union of the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) now estimates their global population at between 50,000 and 100,000 and includes them on its red list of threatened species, external.

Many in Pakistan disapprove of what they see as appeasing the "masters", but for some it is a way to forge better ties with brotherly countries. Over the years Pakistan has relied heavily on the oil-rich Gulf, receiving huge sums in loans and investment.

A former spokesperson from Pakistan's Foreign Office said that they tried to end this "entire embarrassment" but to no avail. The former spokesperson said that "it is evident to many within the government that these trips are useless and futile for us on a diplomatic front but the powers that be have decided to persist with it".

The former official said UAE-Pakistan relations over the past 25 years showed Pakistan had got "nothing" out of the equation.

This winter, too, Pakistan keenly awaited the UAE prince's visit, hoping his hunting trip would help smooth over a recent wrinkle in relations. In 2020 Pakistan was included in a list of countries whose citizens would no longer get visas to work in the UAE, a key source of remittances for millions in the country.

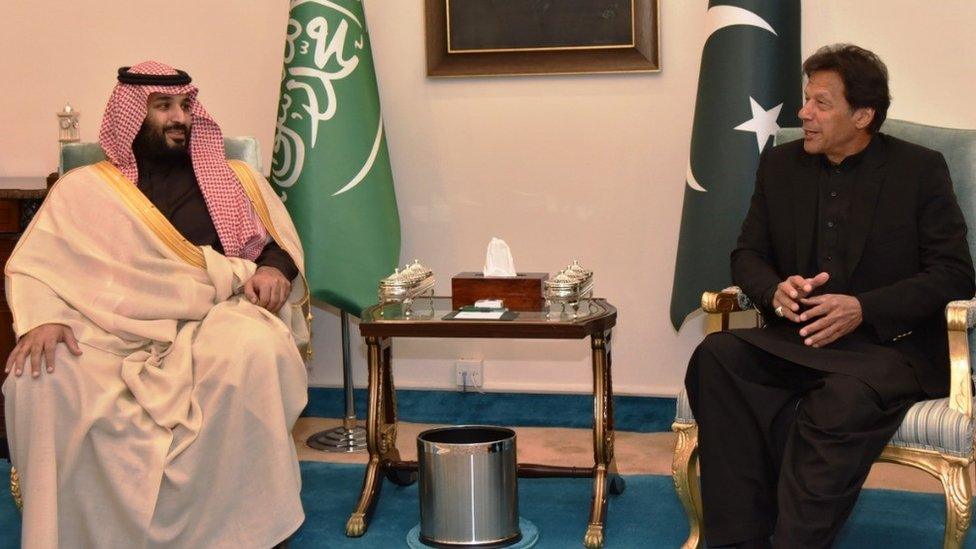

Analysts saw the move as a way of putting pressure on Pakistan, external over issues like the status of Israel and the Kashmir conflict. Prime Minister Imran Khan and his cabinet reject such claims - or indeed any dent in the relationship with the UAE.

However, the hunts are likely to continue.

Pakistan's Supreme Court did try to end them, but a 2015 ban was lifted a year later. While it was in force, the government still issued special permits for Middle Eastern dignitaries, allowing them to hunt under certain conditions.

Haji says the sheikhs have been "good for Pasni" - and he's certainly done well.

Haji Hanif says he is the "sheikh's servant" but doesn't want his sons to follow in his footsteps

He is happy that the sheikh is not only employing locals but also building wells, schools and dispensaries. The only hitch, though, is the schools are without teachers and the dispensaries without medicines or staff.

"The sheikh can only construct something. He cannot ensure the staff also get here. That's the job of the provincial government."

But despite everything, Haji doesn't want his three sons taking on his job.

"I'm the sheikh's servant but my heart doesn't want my children to do what I do. They should go their own way, get into business and make a name for themselves.

"I have spent my life doing what I do and I'm fine with it."

You may also be interested in:

Limited hunting is allowed but conservationists monitoring the migration have reported widespread illegalities

Related topics

- Published17 March 2021

- Published22 January 2016

- Published17 February 2019

- Published18 February 2019

- Published11 February 2016

- Published6 October 2015