Bangladesh at 50: Why climate change could destroy my ancestral home

- Published

As Bangladesh celebrates 50 years of independence, Qasa Alom reflects on how the country his British-Bangladeshi family still calls home is being affected by climate change.

"Can you turn the air-con on?" I asked over and over but none of the grown-ups seemingly could hear me. "It's so hot!"

My mum shot me a look that suggested I would have more than the heat to worry about if I carried on moaning.

We had come to Bangladesh, the country of my ancestors, to see my grandparents, visit our village and, as I was constantly reminded, to "learn about my roots".

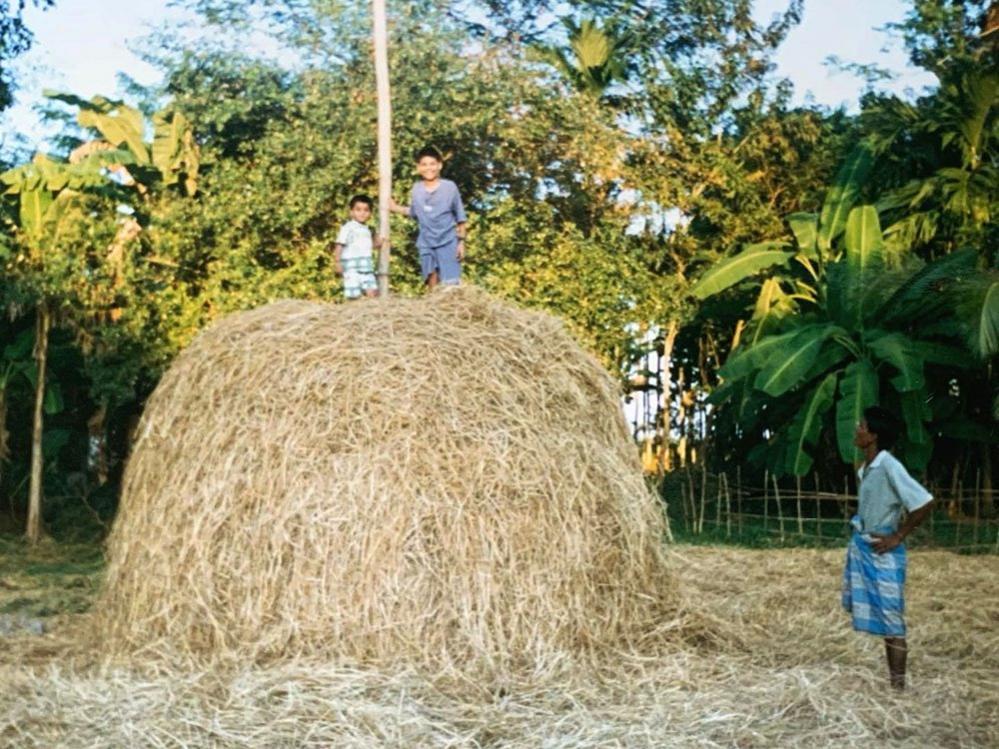

As a child, I had spent my holidays roaming our lands - exploring the rice paddies with my younger brother, watching the farm hands tend to the cows and fishing in one of several fushkunis, or small lakes. It was a giant playground, full of joy, wonder and mischief.

But, that magic had started to wear off as a teen.

One thing I remember vividly about that trip was the moment we were all told to get out of the car that was taking us from the airport to our village.

The road in front of us was completely under water.

We were only about half an hour from our "bari" - village estate - but the journey was about to take an unexpected turn. We all climbed aboard a bamboo boat called a nowka, which then meandered down the murky green water for another two or three hours.

That was 15 years ago - the last time I visited our village.

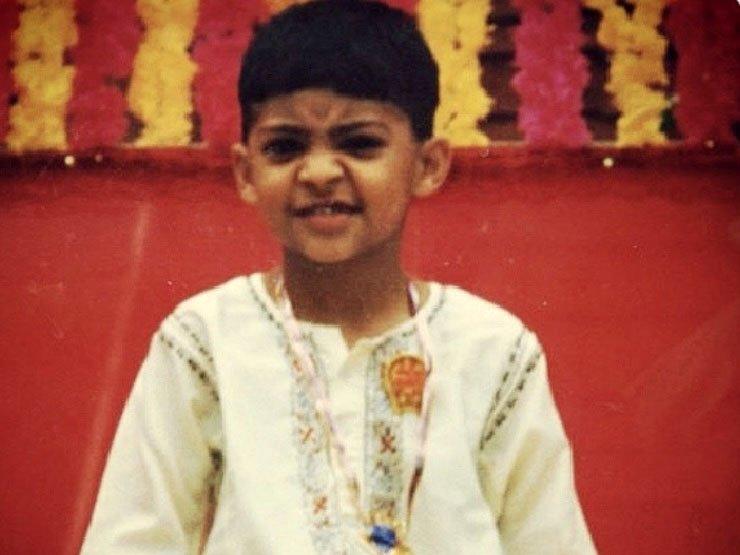

My mum, Ratna, and I talked about this story as we were going through some old photos, which captured 90s fashion, bad haircuts and our land - "a sea of green" - as she describes it. "Your dad dreams of us retiring there, but that won't happen," my mum says. "You, however, need to know what we have there, because that's your inheritance."

Qasa's dad, Saiful, and mum, Ratna, outside the "bari"

My dad was raised in Bangladesh and regularly goes back to look after our estate, visit the school he set up and catch up with the local villagers. Ever since I was a child I've been told that he plans to pass the old family home to my brother, sister and me to look after - but that's not a topic we talk about much any more.

It often ends in an awkward silence.

Like many British Bangladeshis, my father feels duty-bound to help his village and the people he left behind. He has raised funds to build roads and a mosque, for farming equipment, and even to help people with medical bills.

Half the money he earned over the years working in Birmingham's restaurant trade has been sent back to invest in the land and the village, which was named after his great-great-grandfather.

Every summer he would suggest that I return with him to help, but I used to shrug and say, "I don't have time."

My grandmother is the only member of the family who still lives in the bari now - one by one everyone else emigrated abroad, to the UK, Canada, and the United States.

Qasa's brother, sister, cousins and grandmother

But according to my father, "Everything is falling into ruin. It's all going to pieces, nobody is living there and it's just becoming desolate."

My mum explains that generations of my father's family have lived there and that he has worked hard to build it up. "He doesn't want it to be lost."

I've heard these words hundreds of times - but they've never really sunk in until now.

Qasa and his brother return from fishing

Perhaps that's because I'm starting to appreciate my own history and lineage more. As British-Bangladeshis we are now more comfortable with our dual identity and want to find out more about the Bangladeshi part of ourselves.

Or perhaps I just wasn't ready in my late teens and early 20s. I was more interested in conquering the world, rather than preserving our little piece of it.

I am now ready to help my father preserve our home. But there is something else to think about, and it's a far greater threat than neglect and apathy: climate change.

Bangladesh is at the epicentre of the global climate crisis - 80% of the country is floodplain, and it is affected by floods, storms, riverbank erosions, cyclones and droughts. It ranks seventh on the Global Climate Risk Index of countries most affected by extreme weather events, external.

"I jokingly say, Bangladesh is God's laboratory for natural disaster - we have all the disasters except volcanic eruption," says Prof Ainun Nishat, an environmental expert for the Centre for Climate Change and Environmental Research, who advises the Bangladeshi government.

Prof Nishat believes that unless we start to control greenhouse gas emissions today, the situation will become unmanageable.

Bangladesh at 50

The Asian Network's Qasa Alom presents a series of programmes marking Bangladesh at 50

The birth of Bangladesh is on BBC Radio 4 on Monday 29 March at 11:00 - or listen here

The monsoon season from June - October sees incredible rainfall on the lush and fertile land, much of which flows away into one of the three huge rivers that run through the country like giant arteries: the Meghna, the Padma (the Ganges) and the Brahmaputra-Jamuna.

Flooding has always taken place during monsoons - my mum remembers how 30 years ago, she and my dad took a nowka all the way to their front porch.

But the rainfall pattern is becoming more erratic, says Prof Nishat. "It is raining when it is not supposed to rain and it is not raining when it is supposed to rain."

With rainfall fluctuating across the year, flash floods now occur more frequently and ferociously. And our region is particularly susceptible.

Like the majority of the 500,000 British-Bangladeshis, we come from Sylhet, in the north-eastern part of the country. It has high levels of rainfall and it's near the Haor Basin, a large saucer-shaped floodplain, 113 km wide, an area that is undergoing persistent subsidence, external - in some places it has sunk by 12m over the past 200 years, and it is still sinking.

In 2020 Sylhet was hit by huge flash floods that affected thousands of families, whose homes, belongings and livelihoods were swept away by this unforgiving natural disaster.

In fact over a quarter of the country was flooded that monsoon season. Nearly 1.3 million homes were damaged, hundreds of thousands of people were marooned and hundreds died, external.

Bangladesh is one of the world's most densely-populated countries, and many people live in high-risk areas. That is because much of the higher land in Bangladesh has already been built on. At the time of Partition in 1947, Bangladesh - or East Pakistan as it was known then - had a population of about 40 million. Many of those houses were on higher ground, often built by the rich or left by the British.

As time has gone on though, the population in Bangladesh has increased to around 170 million people. Newer communities in developing areas are having to be built closer to floodplains and on lower ground, thus putting more people at risk.

The UN estimates that by 2050 about 20% more of Bangladesh will be under water, external.

Vast areas of land, homes and memories are disappearing forever - including, potentially, my ancestral home. When I asked my parents how the floods have impacted them, my dad turned away. Not through apathy - but pain. My mother told me why.

"Over the years, I hear your dad talking to his mum. The rice crops and everything, it's getting less and less. During the monsoon season it gets flooded, so there's a loss."

Flooding in Sylhet, Bangladesh

That came as a surprise to me. I'd seen flooding on the news and pictures of tin shacks being swept away, but our house is solid. It's on a raised platform and built on strong foundations. But there is a concern for the villagers around us, who depend on us and also on our food, crops and produce.

"The weather is getting more extreme," says Shipu Thakder, a friend of my dad's who helps us out in Sylhet. "It is getting too hot. We don't understand when there will be rain and when there will be thunderstorms. Sunshine is difficult - we can't go outside without an umbrella or protection."

And now that the supply of water can't be relied upon, my father's land is getting drier, leading to village arguments about access to water.

Rice paddy fields owned by Qasa's family

About two-thirds of the country works in agriculture - rice, vegetables, fruit, fishing and farming. It's fertile land, but Prof Nishat is concerned about how a rise in temperature could affect crops and food production.

"It is felt by the ecosystem and biodiversity, so it is going to challenge the productivity of food and that is where we are fighting and struggling," he says. "We are afraid that bad days are ahead."

The concerns about drought and flooding mean that it's harder to predict how much crop people will yield. That, along with the growing population in Bangladesh, means that it's becoming a priority for the government.

Qasa and his brother

Unlike in the past though, Prof Nishat thinks it's something the country is well-equipped to deal with.

"Maybe 20, 30 years back we were dependent on external support for recovering from any natural disaster, but now the economic condition has improved, people's resilience has improved, and their capacity to withstand or manage natural disaster has improved.

"We are one of the most vulnerable countries, we admit, but possibly we are one of the most prepared. We suffered through these disasters regularly, so the people have their own resilience systems to cope with it."

That togetherness and spirit is something every Bangladeshi I have spoken to is very proud of. "Our neighbours are good. We help each other," Shipu told me.

But while people in Bangladesh are doing their bit, it is vital that those of us in Bangladeshi diasporas all over the world to not forget the people who are still there.

"I'll come back with you next year," I told my dad in Bengali. He'd heard me say it a number of times before, but not like this. There was certainty in my voice and he could feel it.

Qasa's mum and dad with the villagers

After the pandemic is over and it is safe to travel, I intend to keep my promise.

The older I get, the more I understand the significance of my ties to my ancestral home, and the more I realise that the land that my father, my grandfather and so many generations before them were raised on, could be flooded and lost forever.